It's My Party (22 page)

“It’s simple. The gender gap is a function of women who rely on government as opposed to those who don’t,” Gingrich explained.

No doubt all that Kellyanne Fitzpatrick had told me was true. No doubt even a great deal of what Jack had said possessed a

basis in fact. But the gender gap doesn’t exist because women are irrational. It exists because they are rational. Just as

any economist or political scientist would predict, women vote their self-interest.

Journal entry:

The Nineteenth Amendment wasn’t a mistake after all. I can’t wait to tell Edita

.

Before running into Gingrich, I had concluded that all the GOP could do about the gender gap was learn to live with it—that

and take out ads in

Redbook

and

Vogue

. Now I thought I saw at least a couple of steps Republicans might take. The first would be to start treating single mothers

with respect.

Society has played a rotten trick on these women, telling them that easy divorce, contraceptives, and abortion on demand would

liberate them. They haven’t. They have liberated men, permitting them to skip out on the children they father—after all, when

a single woman has a child these days, the father can tell himself that she should have used the pill or had an abortion.

If every American followed the precepts of traditional morality, there would certainly be far fewer single mothers. But to

the almost ten million women who are already single mothers, Republican talk about traditional morality can sound like mere

sanctimony. Picture it. You’re a single mother, trying to cook all the meals, change all the diapers, and wipe all the noses

by yourself. Then one day while you’re doing the laundry, a Republican appears on television to drone on about traditional

morality. What do you do? It’s obvious. Pitch the flatiron at him.

Tommy Thompson, the Republican governor of Wisconsin, has demonstrated one way to replace sanctimony toward single mothers

with tangible help. Thompson has reformed Wisconsin’s welfare system, cutting the state’s welfare rolls by more than half.

Yet even as he has moved single mothers off welfare, Thompson has provided them with special assistances. One Thompson reform

helps to ensure that dead-beat dads make their child support payments. Another makes certain that as single mothers undergo

training and then enter the job market, they receive help in locating and paying for child care. Yet another ensures that

teenage mothers receive child care and transportation for free. Wisconsin now spends more on single mothers and their children

than it did before Thompson put his reforms into effect. The reforms aren’t perfect. Some children would no doubt be better

off if their mothers stayed home. Still and all, Thompson’s reforms represent a serious effort to promote self-reliance among

single mothers while treating them with respect. Republicans elsewhere could do a lot worse.

After according respect to single mothers, the second step for the GOP would be obvious. Accord the same respect to single

old ladies.

Forty-five percent of women sixty-five or older are widowed. More than two thirds of them live alone, many cut off even from

their own families. My brother and I saw this with our own mother just a couple of years ago. We always thought of ourselves

as close to her. When my brother moved from the East Coast to Seattle, and then, some years later, I followed him west, moving

to California, it never occurred to either of us that we were leaving her behind. Then she fell ill. There she was, a widow

in a retirement complex in North Carolina, all the way on the other side of the country, suddenly unable to care for herself.

When we were able to move her to Seattle, where she would be close to my brother and his family, she told us that her friends

in the retirement complex envied her. “You’d be surprised how many people here never see their children or grandchildren,”

she said. Exactly.

Now, the problem of caring for the elderly is complicated—and the GOP scarcely needs a writer like me mouthing off about new

programs. I wouldn’t even know how to estimate the costs. (All I can tell you is that the program I kept imagining while my

mother was sick—free around-the-clock care by nurses with the compassion of nuns and the expertise of MDs—wouldn’t be cheap.)

But it has crossed my mind that the GOP might propose a few faith-based initiatives, programs that would shift resources for

the elderly from federal bureaucracies to private organizations, including religious groups. Of course no Republican wants

to see church groups taken over by the feds. But since the church workers who called on my mother were always a lot more cheerful

and friendly than the county social workers the hospital sent, I can’t help thinking that religious groups might be able to

provide old people with better care than can the government. In other words, faith-based initiatives might work.

* * *

The Republican Party’s principal appeal to women, I suspect, will always remain just what the women in Arizona found in the

GOP: a willingness to judge women and men alike according to their individual merits. If the women in Arizona had been Democrats,

they would have had to take me seriously when I asked them about gender politics, producing paragraphs of feminist oratory.

As Republicans, they were free to dismiss me as a fool. That was no mean liberation in itself.

Can the Republican Party ever close the gender gap? The outlook isn’t encouraging. What the GOP preaches is self-reliance.

What single mothers and widows want is help. This is a standoff from which the Democratic Party is only too happy to profit,

promising to shower single women with government largesse. All the same, the GOP ought to do its best to appeal to single

women, making its case for self-reliance while providing whatever assistance it can. It might at least narrow the gender gap.

Then again, it might not. But showing a little heart would do the party good.

O

N THE

B

ORDER OF THE

F

INKELSTEIN

B

OX

Journal entry:

A retired schoolteacher: “Is this your first time in Fresno? It is? Well, you’ll find that people here are

nothing

like people in San Francisco or L.A. We’re more like people in Iowa. We pride ourselves on it.”

A Mexican baby-sitter: “Oh, if I could become legal, I would. But they won’t let me. And I can’t afford to pay the taxes anyway.

My daughter and her children all live on the money I make in this country.”

A

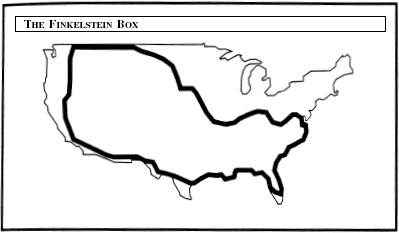

rthur Finkelstein, a Republican political consultant, uses a simple device to show his clients the way the country divides

politically. As you can see, Finkelstein draws a lopsided box on a map of the United States. Inside the box, Republicans do

well, while Democrats do badly. Outside it, Democrats do well, while Republicans do badly. In states whose largest centers

of population lie inside the box, for example, no Democratic candidate for the Senate won a majority in the election of 1996

except Mary Landrieu of Louisiana, and her majority was so narrow—just a few thousand votes—that her Republican opponent,

charging fraud, was able to persuade the Senate to conduct an investigation. (The Senate found a number of irregularities

in the vote count, but sustained Landrieu in her seat.) In the same states two years later, in the election of 1998, five

Democratic candidates for the Senate won majorities, but three of the five did so by less than 10 percent, while one of the

five, Harry Reid of Nevada, did so by a bare one tenth of 1 percent. In states whose largest centers of population lie outside

the box, by contrast, no Republican candidate for the Senate won a majority in the election of 1996, while two years later,

in the election of just three Republican candidates for the Senate won such majorities, one of them, Peter Fitzgerald of Illinois,

managing to do so by a mere 2.9 percent. Inside the box, Republican governors are entirely pro-life. Outside the box, Republican

governors are often pro-choice.

A simple, lopsided box—yet it cleaves the country cleanly in two.

When I first learned about the Finkelstein Box, it brought to mind a valley in Switzerland where I skied when I was a bachelor.

I stayed in a village called Rougemont. Three miles up the road was a village called Saanen. Everyone in Rougemont was a French-speaking

Catholic. Everyone in Saanen was a German-speaking Protestant. Each day I’d wake up in Rougement, exchange a few words of

French with the waitress over breakfast, spend half a day skiing, then have lunch in Saanen, where I’d sit in silence, unable

to exchange a few words with the waitress because I spoke no German. How remarkable, I’d think, that these people have preserved

their separate identities. How quaint. How European.

But a cultural border here? In the United States? This country is supposed to be a melting pot. Immigrants are supposed to

arrive from other countries, learn English, begin intermarrying with those already here, and become, well,

American

. The distinction between the two political identities, one Republican, the other Democratic, that the Finkel-stein Box delineates

may not be as sharp as the distinction between the two cultural identities that I encountered in Switzerland. But it’s still

a lot sharper than any distinction I’d ever thought existed in the United States.

Studying the Finkelstein Box, I noticed that it carved its way through the middle of California. Like the rest of the California

coast, the San Francisco peninsula, which includes Silicon Valley, where I live, lay outside the box. Most of the towns of

the central valley lay inside it. Why? What could be so different about the coast and the central valley? I decided to choose

one town inside the box, then pay it a visit. My finger fell on Fresno.

Journal entry:

As I drove south down the San Francisco peninsula, I listened, as is my habit, to the warm, comforting tones of Bob Edwards

on National Public Radio’s

Morning Edition.

Then, going up through the Pacheco Pass over the Diablo Mountains, I lost the signal. When I came down into the central valley

and hit the scan button, the radio made its way through half a dozen country music stations before it found a grainy NPR signal.

Bob Edwards’s voice came and went, trading places with static. Finally I gave up, listening to Garth Brooks instead

.

Country music. How did Finkelstein know?

Making the three-hour drive to Fresno, I kept a running list of first impressions, noting the ways the central valley differed

from the San Francisco peninsula, as if I were a tourist, which, come to think of it, I was. First I noticed the difference

in radio stations that I commented on in my journal. Then I noticed the difference in cars. On the peninsula, the preferred

vehicles are BMWs, Mercedes-Benzes, Jaguars, and other prestigious foreign makes—even the odd Rolls-Royce shows up from time

to time, wallowing down University Avenue in Palo Alto or nosing into a parking place at the Stanford Shopping Center. But

after the turnoff for Route Five, the interstate to Los Angeles, foreign cars in the central valley all but disappeared, replaced

by endless Fords, Chevrolets, Dodges, Buicks, and Oldsmobiles. The few luxury cars that I spotted were almost without exception

big Cadillacs or fat Lincoln Town Cars, the kinds of cars that retired farmers buy, as if to compensate their bodies after

years spent in the seats of tractors. For several miles I found myself stuck behind a pickup truck. Something about the truck

seemed unusual. When a straw broke free from one of the bales of hay the truck was hauling, smacking against my windshield,

I realized what it was. The truck in front of me was the first pickup I’d seen in months that was being used for a purpose

other than show.

The most striking difference between the San Francisco peninsula and the central valley proved so all-encompassing that it

took a while to sink in. Back in Silicon Valley, people made money. At least that’s the way I always thought of it. I knew,

of course, that what they really made was computer equipment and, increasingly, software. But since so many people in Silicon

Valley labored all day without ever making anything you could hold in your hands—true, you could hold a floppy disk containing

the software in your hands, but all you were holding was the disk, not the software, not

it

—they might as well have been alchemists, transforming thoughts in their minds directly into money in their bank accounts.

In the central valley, people didn’t make money. They grew food. For mile upon mile, I found myself passing orchards, vineyards,

and fields of rice, cotton, and alfalfa. Granted, the agriculture that takes place in the central valley is among the most

sophisticated on earth—Fresno County itself produces more than $3 billion a year in agricultural goods, more, as far as I

can discover, than any other county in the nation. But driving through the central valley still felt appealingly simple and

basic. All you had to do to see how people made their living was look out the window. I might as well have been touring Kansas.

Before long I noticed a bumper sticker on a Lincoln Town Car that almost persuaded me I was. “Live Better,” the bumper sticker

said. “Vote Republican.”