It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War (16 page)

Read It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War Online

Authors: Lynsey Addario

Iraqis descended on every building like ants, stripping each of them of its possessions. Men rode down the street with massive air-conditioning units—under Saddam, owned by only the wealthiest Iraqis—on their bicycles. Furniture was piled high on people’s heads. Chairs, couches, beds, and tables all appeared to be walking around the streets. Young men swam in the artificial lakes surrounding Saddam’s massive marble palaces while families picnicked on the lush grounds and toured the stately palace atriums.

We headed to Mosul to meet with General David Petraeus, the U.S. commander of the 101st Airborne Division, which had set up a major base in one of Saddam’s palaces. Security was lax. Many Iraqis loved the Americans then, and Americans loved Iraqis then, too. I was so homesick for conversation not filtered through an interpreter that I spent the afternoon flirting with the strapping and dirty eighteen-year-old soldiers, regressing to my high school vocabulary and demeanor and paging through well-read copies of

Maxim

magazine. A cafeteria with hot food was erected in the rose garden. Dozens of high-level officers sat behind computer screens and satellite feeds running off generators. It was an incredible display of technology in a country that had little running water and unreliable electricity since the invasion. It was also a symbol of victory: hundreds of U.S. troops operating out of one of Saddam’s homes.

Kurdish

peshmerga

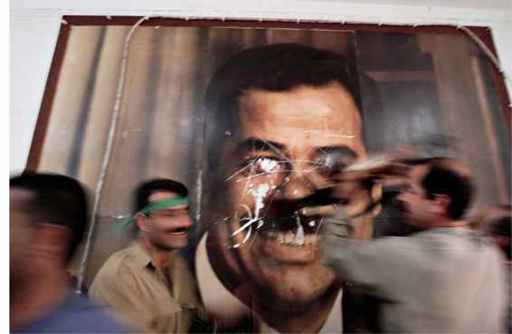

soldiers deface a poster of former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein in the Kirkuk Governorate building in Kirkuk hours after it fell from the Iraqi central government’s rule, April 10, 2003.

I was set up with a cot alongside about thirty soldiers in a giant room. It opened up to a grand terrace overlooking the city. I stepped out to the balcony to work under the stars and enjoy the cool breeze. I had a good day of shooting behind me and another one ahead of me. I just smiled out there, alone on the balcony, and knew that this feeling could sustain me forever.

• • •

U

NLIKE THE REST

of the press corps that descended on Baghdad, in addition to my assignment with Elizabeth I had been asked by

Time

magazine to stick around and work in the north in the weeks immediately following the fall of Saddam. Salim, who stayed on as my interpreter, was forced to live vicariously through the sensuous, alluring dispatches from his best friend, Dashti, who had traveled to Baghdad to continue as interpreter for Elizabeth. For many young Kurds, Baghdad was a chance to experience big-city life, despite the fact that most stores were still closed, the electricity was still cut, and Arabs and Kurds didn’t always love each other. The prostitutes of Baghdad were an irresistible temptation for Dashti and Salim, whose sexual experiences were limited to fleeting moments of soft porn on satellite TV.

“Can we please go to Baghdad already?” Salim pleaded day after day. “Dashti is there, and he says there are so many beautiful women!”

“Salim, I am on assignment, and they want me in Mosul. As soon as this assignment ends, we can go.” I wasn’t about to compromise my work so my interpreter could lose his virginity. But this experience with interpreters, I was learning, was a typical one: We were living with them day in and day out, and they became close friends, often like family. There were few other people I spent such extended periods of time with, day and night, and I worried about their desires, hardships, and needs as much as they did mine.

Dashti called several times a day. “A friend has arranged four sisters in this brothel . . . I have met all of them . . . I will make sure they are ready for you.”

Soon enough I was off to Baghdad to shoot another story with Elizabeth. Salim began preparing himself, squirming in the passenger seat with excitement. As we drove along endless stretches of barren desert highway my satellite phone rang relentlessly with Dashti on the other end: “The sisters are ready for Salim!”

Dashti, the ultimate fixer, had done the necessary groundwork for his best friend’s deflowering, as if he were arranging just another interview.

I felt some sense of responsibility. I had spent the last two months consumed with anything but the normalcy of life: arranging drivers, preparing vehicles with spare tires and extra containers of gas, looking for hotel rooms with south-facing windows for satellite reception, trying to wake up early enough on three hours of sleep to take advantage of the soft morning light and its long shadows. As we approached Baghdad, my thoughts, my responsibilities, shifted to Salim and the loss of his virginity.

Where the hell did one start explaining the birds and the bees to a twenty-three-year-old Iraqi Kurdish boy who has never kissed a woman? I started with condoms and AIDS.

“There’s no AIDS in Iraq,” he said.

Children swim in an artificial lake surrounding former Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein’s palace in Mosul, April 29, 2003.

U.S. Marines take a break to shave in front of one of Saddam’s presidential palaces the day Tikrit fell from Republican Guard rule in Iraq, April 14, 2003.

“Well, OK, but do you know what to do?” My voice trailed off. I couldn’t explain foreplay to a Muslim man when I was unmarried and allegedly a virgin. I let it go. I just hoped Salim would make it to work the next day in time for the early morning light.

• • •

I

HAD BEEN ANTICIPATING

arriving in Baghdad for many months, but by the time I pulled into the Hamra Hotel, where many of the foreign journalists were staying, I barely had the energy to familiarize myself with a new city. Baghdad was relatively prosperous in 2003. Under Saddam it had a proper infrastructure, with roads, electricity, and water; green spaces and private clubs; and riverside fish restaurants along the Tigris. Compared with Afghanistan’s, Iraq’s population was well educated. Arabs had traveled from across the Middle East to attend the university in Baghdad. Those first few weeks life went on in a surprisingly routine way. The city didn’t feel particularly dangerous. Civilians were out; shops were open; there were cars on the streets. Electricity and water functioned in select neighborhoods.

Elizabeth and I stayed at a rented apartment across from the Hamra, in a residential neighborhood named Al-Jadriya. In the beginning the social life of most journalists revolved around the Hamra pool, drinking beer and wine and watching the muscular correspondent for the

Christian Science Monitor

, Scott Peterson, do pull-ups from the fire escape in a teeny-weeny black Speedo. A few times a month a vivacious, blond California native named Marla Ruzicka, the founder of an organization that counted civilian casualties in Afghanistan and Iraq, arranged salsa parties for all the journalists and aid workers who didn’t have security restrictions. The BBC radio correspondent Quil and I would dance for hours on end until it was time to return to our respective rooms.

During one of the first summer parties, a correspondent asked, “Who has gotten separated since the start of the war?” and almost everyone in the room raised their hand. There were so many divorces after the fall of the Taliban, many more after the fall of Saddam Hussein. Our partners got tired of waiting, and rightly so. Many accused us of cheating, but more often than not we were cheating with our work. No other period in our careers would ever compare with the importance of those post-9/11 years. But some were also taking advantage of the double lives we led as journalists, and Baghdad, especially, became a laboratory for reckless romance. Home was a sort of parallel existence: our ever-present real life versus this exhilarating temporary one.

When I got back to my room, I always called Uxval. I recounted scenes from the day and tried to keep him involved in my life from a distance. But while my heart missed him, my passion had shifted to Baghdad. I was too busy, too absorbed by the rapidly evolving news, too enthralled with Iraq to devote much time to something or someone beyond my immediate grasp.

In fact, the hardest part of those early days was deciding what to cover first. A dictatorship’s secrets had been spilled into the streets of Baghdad. We needed to document the truth.

At a mass grave called al-Mahawil, sixty miles south of Baghdad, men and women weaved aimlessly around the open ditches where dozens of bodies had been dug up. Laid neatly in rows were plastic bags containing the remnants of each body, its tattered clothes, its strands of hair. Some had identification cards, some did not. Women in black

abaya

s, the floor-length, curtainlike scarves worn by conservative women all over the Middle East, shuffled from grave to grave weeping, screaming, arms thrust into the air. They were the widows and mothers of the disappeared men that Saddam’s loyalists executed during the Shiite uprising of 1991.

Soldiers with the Fourth Infantry Division, Third Brigade, from the First Batallion, 68th Armored Regiment, momentarily detain and search Iraqi men during a night patrol north of Baghdad near the Balad Air Base in Iraq, June 27, 2003. Minutes after this image was shot, an Iraqi civilian crossed over what was possibly a remotely detonated explosive device that had been set in a road and intended for the U.S. troops. The blast severely injured the man.