Authors: Catherine Merridale

Ivan’s War (12 page)

Recruiting was a cumbrous process that usually dragged on for two or three months every year. In each district it was the duty of the local military soviet. These had the right to sift and reject sick or insane men and also to review claims for exemption. They also checked police records, for known enemies of the people were not trusted to bear arms. The lads who came before them after all these checks were not completely raw in military terms. All had been to some local school, and most would know their country needed to prepare for war. Some new recruits might even have clapped eyes on a rifle or a gas mask at a summer camp somewhere; they would certainly have listened to as many lectures on the Workers’ and Peasants’ Red Army as any teenager could take. This army could seem like a route to manhood, an adventure, and there were always youths who declared themselves proud to be called up. Not a few, especially in the cities, volunteered, but for the rest, the scenes at home were much as they had always been. The road still beckoned and the mothers wept. The men would gather up the few things they could carry – a couple of changes of underclothes, some sugar and tobacco – and stuff them into a canvas bag or cardboard case. And then

they walked – for few had grander means of transport – to the recruitment point.

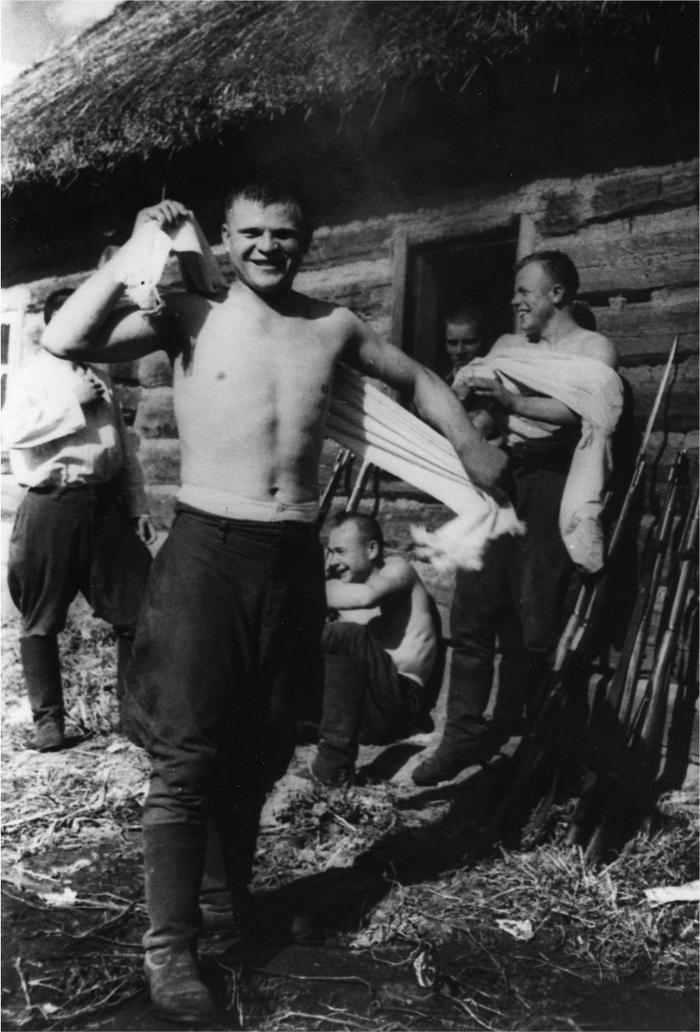

Soldiers at the banya, September 1941

‘Our military training began with a steam bath, the disinfection of our clothes, a haircut that left our scalps as smooth as our faces, and a political lecture,’ a recruit from this time remembered.

22

For many in the audience, that lecture would have echoed through a hangover. Young men were very often drunk by the time they arrived in their units. It was a tradition, like many others, that dated from tsarist times.

23

The drinking began before they left home and carried on for several days. The authorities may even have connived at it, since vodka stilled the men’s anxieties more rapidly than group lectures or extra drill. Recruits might pass out on the train, the argument ran, but if they were unconscious it was easier to ship them off to any kind of hell.

24

Bleary-eyed, then, and not certain quite where they were, the conscripts stood in ragged lines and waited to receive their kit. Whatever their civilian selves – sons of the village or of some factory or mining town – they would fold up the things in which they had spent their former lives and pull on dull green uniforms, the clothes of new identity. They stepped into rough woollen trousers and pulled on a jacket. They were also issued with a belt, overcoat and boots. These things were theirs to wear and maintain every day. But their underclothes – an undershirt and pants – were issued on a temporary basis. They learned that they would hand these items in for regular – if not particularly frequent – laundering, and that they would receive a clean set in exchange. In fact, they seldom got the same ones, or even a complete issue, back each time. It was a small humiliation, another thing, an intimate one, that they could not control.

A senior sergeant teaches a young recruit to wrap footcloths

Unless they brought their own, which some did, recruits were never given socks. This was an army that marched in footcloths –

portyanki

. These strips of cloth wound around the feet and ankles, binding them like bandages. They were alleged to protect against blisters. A veteran smiled at that idea. ‘I think socks would have been more comfortable,’ he said. But it was just a whisper, not dissent.

Portyanki

, after all, were cheaper and less personal: one size would do for all. It took a while to learn to wrap them, and the process caused

delays and chaos at reveille for ages, but the strips of cloth were universal issue, and they were used by men and women through the war. ‘They were the only things that made those boots they gave us fit,’ a woman veteran remembered. ‘And yes, we were glad to have the boots as well.’

Only the officers were given handguns, usually Nagan revolvers, a design that dated from the 1890s. It was an officer’s exclusive privilege, too, to get an army wristwatch. Private soldiers got the bags and holsters, but much of the time they had nothing to put in them. Their tally of assorted empty luggage included a field bag, a bag for clothes, a bag for carrying biscuits, a strap for fastening their overcoat, a woollen flask cover, a bag for the things they had brought from home, a rifle sling, cartridge boxes and a cartridge belt.

25

The weapons themselves, and even the ammunition rounds, were so precious that most men did not handle them until they took part in a field operation. But they were issued with an army token, the proof of their new status, and a small kettle. The things that had a personal use were the most treasured. ‘Frontline soldiers would sometimes, in panicky retreats, throw away their heavy rifles,’ wrote one veteran, Gabriel Temkin. ‘But never their spoons.’

26

The men would lick them clean after each meal and store them in the tops of their boots.

The new recruits would soon be looking for their beds. In this, as in so many other ways, the generation that would join from 1938 was out of luck. The army had been expanding rapidly. In 1934, it numbered about 885,000 officers and men. By the end of 1939, as the reservists were called up in preparation for war, that figure had grown to 1,300,000.

27

Among the many problems caused by the expansion was a housing crisis. Army regulations stated that each man should have a living space of 14.6 cubic metres, 4.6 square metres of which – think of six feet by eight – were to comprise the floor.

28

But this was optimistic talk. Even officers could not expect adequate quarters. ‘Collective farmers have a better deal than our officer corps,’ a communist official in the Leningrad military district wrote in January 1939. The new arrivals described their conditions as ‘torture’.

29

‘It would be better for me to kill myself than to go on living in this hole,’ an officer recruit remarked. Complaining landed one cadet who demanded ‘the quarters to which officers are entitled’ in the guardhouse for three days. Tuberculosis rates among all ranks tended to rise in the year after they joined up, as did the incidence of stomach infections. In one case 157 cadets in a single barracks were taken to hospital in their first ten days.

30

Private soldiers were also crowded into smaller than the regulation space.

31

In fact, only the lucky ones would find they had a billet and a roof.

The mobilization plan of 1939 was so ambitious that many turned up at their bases to discover that there was no barracks at all. In that case they could look around the town for accommodation of their own or sleep on the bare ground. Either way, they might have nothing under them but straw. The army provided blankets, but mattresses were always scarce and there were never enough plank beds for the swelling number of recruits. The straw, though warm, was an ideal refuge for lice.

32

A stroll around the camp would not have cured a young man’s hangover or his homesickness. Communal facilities of any kind were neglected in the Soviet Union. The culture of material goods had spawned a thriving black market. If something could be stolen, skimped or watered down, a huckster with the right contacts was always near at hand. Meanwhile, the shortages and management problems that dogged the centrally planned economy bore dismal fruit. A Communist Party inspector visiting the Kiev military district in May 1939 found kitchens heaped with rubbish, meat stores stinking in the heat, and soldiers’ dining rooms that still lacked roofs or solid floors. Moving across the yard towards the bathrooms, he noted that ‘the unclean contents of latrines is not removed, the surveyed lavatories have no covers. The urinals are broken … The unit, effectively, has no latrine.’

33

The case was not unusual, as other reports showed. ‘Rubbish is not collected, dirt is not cleaned,’ another note records. ‘The urinals are broken. The plumbing in the officers’ mess does not work.’

34

Hygienic measures were neglected everywhere. The slaughterhouse that provided soldiers in Kursk province with meat had no running water, no soap, no meat hooks and no special isolator for sick animals. The staff who worked there had received no proper training and they had not been screened for infectious diseases of their own. Their filthy toilet was a few yards from the meat store, and like many others at the time, it had no doors. ‘Even the meat is dirty,’ the inspector wrote.

35

Food was a standing grievance everywhere. This is true of all armies, as budget catering and hungry men are on a fixed collision course, but the Soviet case belongs in a special class. However cold it was outside, the barracks kitchen would be rank and fogged with grease. Lunch – a soup containing sinister lumps of meat, due to be served with black bread, sugar and tea – steamed on wood stoves in giant metal pots. ‘At home,’ one conscript complained, ‘I used to eat as much as I needed, but in the army I have become thin, even yellow.’ ‘The grub is awful,’ reported another. ‘We always get vile cabbage soup for lunch, and the bread is the worst: it’s as black as earth and it grinds against your teeth.’ In January 1939 alone there were at

least five cases where groups of soldiers refused to eat, striking in the face of another inedible meal. In the first three weeks of the same month, army surgeons reported seven major instances of food poisoning, the worst of which, involving rotten fish, left 350 men in need of hospital treatment.

36

Dead mice turned up in the soup in the Kiev military district; sand in the flour, fragments of glass in the tea and a live worm featured on menus elsewhere at the same time.

37

Two hundred and fifty-six men suffered disabling diarrhoea in March when the tea they were served turned out to have been brewed with brackish, lukewarm water.

38

A young conscript from the Caucasus republic of Georgia – a region famous even then for its good food – deserted after a few weeks in Ukraine, leaving behind a note that singled out the Soviet army diet. ‘I am going back to the mountains,’ he concluded, ‘to eat good Georgian food and drink our wine.’

One answer was to grow food on the army’s land. Here was one thing that former peasants could really be asked to do. As Roger Reese records in his account of pre-war army life, ‘By the late summer of 1932, one regiment already had more than two hundred hogs, sixty cows, more than one hundred rabbits and forty beehives.’

39

Nothing had changed by 1939. The soldiers dug potatoes and cut hay, they milked cows and they slaughtered pigs.

40

The work could be heavy, dirty and cold, so field duties were sometimes used as punishments. In all cases, farming took the men away from their military training and distracted them from the real purpose of their army service. But everyone’s priority was filling empty stomachs, and successful regimental farms made a real difference to the men’s diet. They also helped to lift morale. This was a time when almost everyone – not only soldiers, but collectivized peasants and even some communities of workers – was going hungry. While brightly painted new kiosks sold ice cream to the masses, most people were still forced to scrape and queue to buy staples like butter and meat. The soldiers had a guaranteed allocation, even if the quality was poor. It is a bleak commentary on Soviet life, but Reese himself concludes that ‘despite their poor accommodations, officers and soldiers generally had a slightly higher standard of living in the 1930s than the rest of Soviet society’.

41