Ivan’s War (2 page)

Authors: Catherine Merridale

There is no shade in the centre of Kursk in July. Achieving this required an effort, for Kursk stands on some of the richest soil in Russia, the black earth that stretches south and west into Ukraine. Wherever there is water here there can be poplar trees, and all along the roads that lead to town the campion and purple vetch climb shoulder-high. The land is good for vegetables, too, for the cucumbers that Russians pickle with vinegar and dill, for cabbages, potatoes and squash. On summer Friday afternoons the city empties rapidly. Townspeople go out to their

dachas

, the wooden cottages that so many Russians love, and the fields are dotted with women stooping over watering cans. The tide reverses on weekdays. The countryside flows inwards to the city. Step away from the centre and you will find street vendors hawking fat cep mushrooms, home-made pies, eggs, cucumbers and peaches. Walk round behind the cathedral, built in the nineteenth century to celebrate Russia’s victory over Napoleon Bonaparte, and there are children squatting on the grass beside a flock of thin brown goats.

All this exuberance is banished from the central square. A hundred years ago there were buildings and vine-clad courtyards in this space, but these days it is all tarmac. The weather was so hot when I was there that I was in no mood to count my steps – two football pitches, three? – but the square is very, very large. Its scale bears no relation to the buildings on its edge and none at all to local people getting on with life. Taxis – beat-up Soviet models customized with icons, worry-beads and fake-fur seat covers – cluster at the end nearest the hotel. At half-hourly intervals, an old bus, choking under its own weight, lumbers towards the railway station several miles away. But living things avoid the empty, uninviting space. Only on one side, where the public park begins, are there trees, and these are not the shade-producing kind. They are blue-grey pines, symmetrical and spiky to the touch, so rigid that they could be made of plastic. They stand in military lines, for they are Soviet plants, the same as those that grow in any other public space in any other Russian town. Look for them by the statue of Lenin, look near the war

memorial. In Moscow you can see them in a row beneath the blood-red walls of the Lyubyanka.

This central square – Red Square is still its name – acquired its current shape after the Second World War. Kursk fell to the advancing German army in the autumn of 1941. The buildings that were not destroyed during the occupation were mined or pitted with shots in the campaign to retake the place in February 1943. Many were ripped apart one bitter winter when the fuel and firewood ran out. Old Kursk, a provincial centre and home to about 120,000 people in 1939, was almost totally destroyed. The planners who rebuilt it had no interest in conserving its historic charm. What they wanted of the new Red Square was not a space where local people could relax – there were few enough of them left, anyway – but a parade ground for an army whose numbers would always swamp the city’s population. In the summer of 1943, well over a million Soviet men and women took part in a series of battles in Kursk province. The rolling fields that stretch away towards Ukraine saw fighting then that would decide not only Russia’s fate, or even that of the Soviet Union, but the outcome of the European war. When that war was over, the heart of the provincial city was turned into an arena for ceremonies of similarly monstrous size.

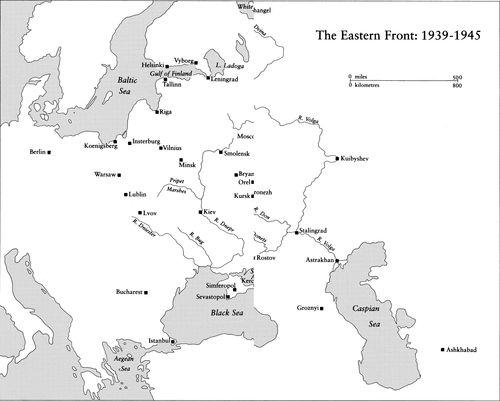

Whatever measure you decide to take, this war defied the human sense of scale. The numbers on their own are overwhelming. In June 1941, when the conflict began, about 6 million soldiers, German and Soviet, prepared to fight along a front that wove more than 1,000 miles through marsh and forest, coastal dune and steppe.

1

The Soviets had another 2 million troops already under arms in territories far off to the east. They would need them within weeks. As the conflict deepened over the next two years, both sides would raise more troops to pour into land-based campaigns hungry for human flesh and bone. It was not unusual, by 1943, for the total number of men and women engaged in fighting at any one time on the Eastern Front to exceed 11 million.

2

The rates of loss were similarly extravagant. By December 1941, six months into the conflict, the Red Army had lost 4.5 million men.

3

The carnage was beyond imagination. Eyewitnesses described the battlefields as landscapes of charred steel and ash. The round shapes of lifeless heads caught the late summer light like potatoes turned up from new-broken soil. The prisoners were marched off in their multitudes. Even the Germans did not have the guards, let alone enough barbed wire, to contain the 2.5 million Red Army troops they captured in the first five months.

4

One single campaign, the defence of Kiev, cost the Soviets nearly 700,000 killed or missing

in a matter of weeks.

5

Almost the entire army of the pre-war years, the troops that shared the panic of those first nights back in June, was dead or captured by the end of 1941. And this process would be repeated as another generation was called up, crammed into uniform and killed, captured, or wounded beyond recovery. In all, the Red Army was destroyed and renewed at least twice in the course of this war. Officers – whose losses ran at 35 per cent, or roughly fourteen times the rate in the tsarist army of the First World War – had to be found almost as rapidly as men.

6

American lend-lease was supplying the Soviets with razor blades by 1945, but large numbers of the Red Army’s latest reserve of teenagers would hardly have needed them.

Surrender never was an option. Though British and American bombers continued to attack the Germans from the air, Red Army soldiers were bitterly aware, from 1941, that they were the last major force left fighting Hitler’s armies on the ground. They yearned for news that their allies had opened a second front in France, but they fought on, knowing that there was no other choice. This was not a war over trade or territory. Its guiding principle was ideology, its aim the annihilation of a way of life. Defeat would have meant the end of Soviet power, the genocide of Slavs and Jews. Tenacity came at a terrible price: the total number of Soviet lives that the war claimed exceeded 27 million. The majority of these were civilians, unlucky victims of deportation, hunger, disease or direct violence. But Red Army losses – deaths – exceeded 8 million of the gruesome total.

7

This figure easily exceeds the number of military deaths on all sides, Allied and German, in the First World War and stands in stark contrast to the losses among the British and American armed forces between 1939 and 1945, which in each case amounted to fewer than a quarter of a million. The Red Army, as one recruit put it, was a ‘meat-grinder’. ‘They called us, they trained us, they killed us,’ another man recalled.

8

The Germans likened it, dismissively, to mass production,

9

but the regiments kept marching, even when a third of Soviet territory was in enemy hands. By 1945, the total number of people who had been mobilized into the Soviet armed forces since 1939 exceeded 30 million.

10

The epic story of this war has been told many times, but the stories of those 30 million soldiers still remain unexplored. We know a great deal about British and American troops, and they have become the case studies for much of what is known about combat, training, trauma and wartime survival.

11

But when it comes to the war of extremes along the Soviet front, perversely, most of what we know concerns soldiers in Hitler’s army.

12

Sixty years have passed since the Red Army triumphed, and in its turn the state for which the Soviet soldiers fought has been swept away, but Ivan, the Russian

rifleman, the equivalent of the British Tommy or the German Fritz, remains mysterious. Those millions of conscript Soviet troops, for us, the beneficiaries of their victory, seem characterless. We do not know, for instance, where they came from, let alone what they believed in or the reasons why they fought. We do not know, either, how the experience of this war changed them, how its inhuman violence shaped their own sense of life and death. We do not know how soldiers talked together, what lessons, jokes or folk wisdom they shared. And we have no idea what refuges they kept within their minds, what homes they dreamed of, whom and how they loved.

A soldier’s farewell to his wife and children, Don Front, 1941

Theirs was no ordinary generation. By 1941, the Soviet Union, a state whose existence began in 1918, had already suffered violence on an unprecedented scale. The seven years after 1914 were a time of unrelenting crisis; the

civil war between 1918 and 1921 alone would bring cruel fighting, desperate shortages of everything from heating fuel to bread and blankets, epidemic disease and a new scourge that Lenin chose to call class war. The famine that came in its wake was also terrible by any standards, but a decade later, in 1932–3, when starvation claimed more than 7 million lives, the great hunger of 1921 would come to seem, as one witness put it, ‘like child’s play’.

13

By then, too, Soviet society had torn itself apart in the upheaval of the first of many five-year plans for economic growth, driving the peasants into collectives, destroying political opponents, forcing some citizens to work like slaves. The men and women who were called upon to fight in 1941 were the survivors of an era of turmoil that had cost well over 15 million lives in little more than two decades.

14

‘The people were special,’ the old soldiers say. I heard this view expressed dozens of times in Russia, and the implication was that torment, like a cleansing fire, created an exceptional generation. Historians tend to accept this view, or at least to respect the evidence of stoical endurance and self-sacrifice on the part of an entire nation. ‘Material explanations of Soviet victory are never quite convincing,’ writes Richard Overy in his authoritative history of Russia’s war. ‘It is difficult to write the history of the war without recognising that some idea of a Russian “soul” or “spirit” mattered too much to ordinary people to be written off as mere sentimentality.’

15

‘Patriotism,’ the veterans would shout at me. ‘You will not find it among our young people now.’ This may be true, but few have reflected on the motivation of soldiers whose lives had been poisoned by the very state for which they were about to fight. Few wonder, too, what insights future soldiers might have gleaned from parents or from older comrades who had survived other wars, seen other Russian governments or learned the way to stay alive by watching just how others died. The soldiers’ stories are a web of paradox, and sixty years of memory have only added to the confusion.