Jack Frake

Authors: Edward Cline

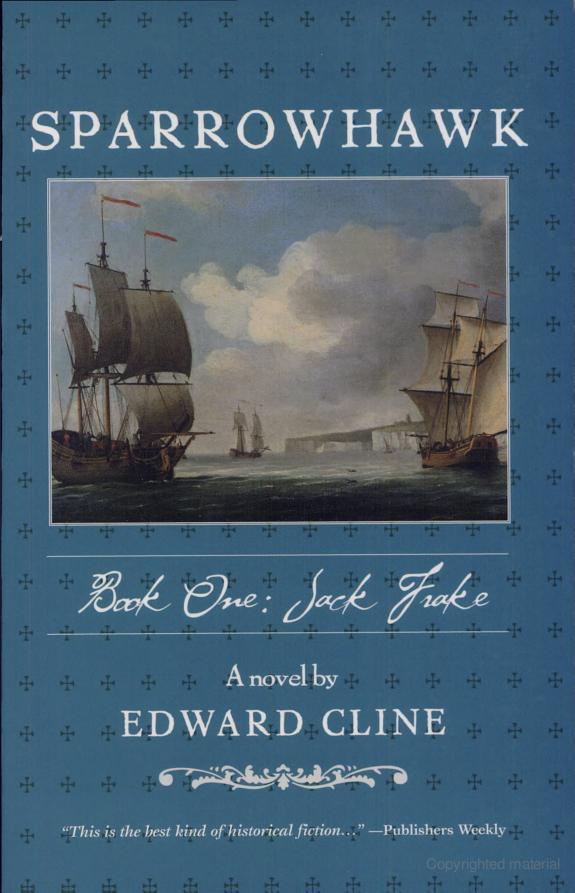

SPARROWHAWK

JACK FRAKE

Book One in the Sparrowhawk Series

A novel by

EDWARD CLINE

ebook ISBN: 978-1-59692-943-2

M P Publishing Limited

12 Strathallan Crescent

Douglas

Isle of Man

IM2 4NR

British

Isles

Telephone: +44 (0)1624 618672

email: [email protected]

MacAdam/Cage Publishing

155 Sansome Street, Suite 620

San Francisco, CA 94104

www.macadamcage.com

Copyright © 2001 by Edward Cline

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cline, Edward, 1946 —

Sparrowhawk—Jack Frake : a novel / by Edward Cline.

28 chapters — (Sparrowhawk ; bk. 1)

ISBN: 1-931561-00-1 (alk. paper)

1. United States—History—Colonial period, ca. 1600-1775—Fiction.

2. Great Britain—History—george II, 1727-1760—Fiction.

3. Immigrants—Fiction. 4. Smugglers—Fiction. 5. Boys—Fiction.

I. Title. II. Title: Jack Frake.

GSH 2010

Book design by Dorothy Carico Smith.

Publisher’s Note: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the

product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

I am indebted, first and foremost, to two individuals, no longer with us. One confirmed my approach to life, the other confirmed its direction: Ayn Rand, the novelist-philosopher, whose novels I discovered, when a teenager, in the vandalized library of a suburban Pittsburgh boys’ home; and David Lean, the British director, whose

Lawrence of Arabia

I saw the same year, an event that cemented my ambition to become a novelist.

Special fond thanks go to Wayne Barrett, former editor of the

Colonial Williamsburg Journal

, who was certain this novel would see the light of day after having read the first page long ago; and to the BookPress in Williamsburg, whose partners, John Ballinger and John Curtis, also encouraged me and allowed me to rummage through their valuable stock on the track of ideas and materials.

Further debts of thanks are owed to the staff and past and current directors of the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library at Colonial Williamsburg for their assistance; to many of Colonial Williamsburg’s costumed “interpreters,” too numerous to name here, for the passion, lore, and information they imparted; and to the staff of the Earl Gregg Swem Library at the College of William & Mary, Williamsburg.

Pat Walsh, editor, together with Robert Tindall and John Gray, have my gratitude for their incisive suggestions and innumerable corrections, and for sharing my confidence that this novel will find a large and appreciative readership.

Lastly, I owe a debt of thanks to the Founders for having given me something worth writing about, and a country in which to write it.

The special province of drama

“is to create… action… which springs

from the past but is directed toward the future and is always

great with things to come

.”

— Aristotle,

On Drama

CONTENTS

Chapter 1: The Map

Chapter 2: The Cottage

Chapter 3: The Cubbyhole

Chapter 4: The Spirits

Chapter 5: The Globe

Chapter 6: The Sea Siren

Chapter 7: The Impostor

Chapter 8: The Skelly Men

Chapter 9: The Caves

Chapter 10: The Covenant

Chapter 11: The Career

Chapter 12: The Commissioner Extraordinary

Chapter 13: The Proclamation

Chapter 14: The Laughing Lamb

Chapter 15: The Stagecoach

Chapter 16: The Highwaymen

Chapter 17: The City

Chapter 18: The Betrayal

Chapter 19: The Tour

Chapter 20: The Courier

Chapter 21: The Spy

Chapter 22: The Trap

Chapter 23: The Major

Chapter 24: The World Turned Upside Down

Chapter 25: The Prisoners

Chapter 26: The Plea

Chapter 27: The Trial

Chapter 28: The Conquering Hero

Epilogue: The Sparrowhawk

Chapter 1: The Map

I

T IS WHEN THE FOG CLEARS, AND THE MOON AND THE STARS ARE BRILLIANT

, and the white sails of faraway ships on an invisible horizon are sharp and almost luminescent as they glide past on their grand, unknown errands, that a boy of ten may take stock of himself and of the world he knows. This is a quiet, precious time; he knows that the world is not so much focused on him, as he on it, through a special lens in his inchoate soul. The brevity and suddenness of this moment, which strikes without warning such souls as do not submit to the intrusive humdrum of their daily lives, signals its own importance, for its incandescent violence must make one passionately certain that one is a worthy crucible.

Jack Frake was a boy of ten, and tonight he was such a crucible.

The wind that gusted around him in the cubbyhole of rocks, on the edge of a cliff high over the shore below, surged through the coarse material of his clothing and chilled him so that he shivered. But the uncontrollable spasms in his knees and shoulders made him aware only that this same wind drove the distant sails and lifted their pennants and banners to snap proudly in the cold air.

The charge that ignited the moment for him was a map, the first he had ever seen. He had learned some hours ago that he lived in Cornwall, and that his secret cubbyhole sat precisely on the southern edge of a great island, England. Where before he had been aware only of the hills, fields

and cliffs on the one side, and the ocean on the other, now he held in his mind an abstraction, and it was drawn from a part of the world he knew. Beyond that tiny realm lay the thrilling, unexplored empire of the island. The island itself was big enough for his ambition; he had the crazy notion that he could run along the path of its outline from the point where he sat and return to it days later from the opposite direction, not to impress himself with the magnitude of the island, but to prove his joyful possession of it.

The map belonged to Robert Parmley, rector of the parish of St. Gwynn-by-Godolphin, whose church was a five-mile walk from Jack Frake’s home in Trelowe. The parson, once a rising authority on antiquities, was now a lonely, shunned old man whose indiscreet, risqué remarks decades ago on the private life of a prelate of the Church of England had been forgotten by both the prelate and the parson, but whose gravity was such that he had been condemned to permanent assignment in this spiritually bovine parish. Here he preached to sparsely attended services, helped the poor, infirm, and old when he could, and collected a few worn coppers, aside from tithes, from villagers and cottagers who could spare the time or the care to put their children under his tutelage.

From Jack Frake’s locally notorious parents he had exacted only a promise from them to appear regularly in church once a month. The promise was not kept — the parson suspected that Cephas and Huldah Frake merely wanted to be rid of the boy for a while — but Jack Frake was the brightest youth he had ever undertaken to introduce to the rudiments of reading, writing and ciphering, and so he was reluctant to ban the boy from the converted stable which served as a schoolhouse in the back of the rectory.

This afternoon the boy had done remarkably well in reading passages from Ecclesiastes, in copying words onto his slate as Parmley dictated them to his seven pupils, and in exercises in two-digit subtraction. He felt a curiously clean duty — something verging on a desire — to reward him. Jack Frake’s progress had been relentless, while the other boys had to be re-drilled in the subjects over and over again. And so, when he had dismissed the six other boys for the day, Parmley pulled out from his makeshift desk a great book of maps. The book had been sent to him, many years before, by his brother, a successful printer and cartographer in London.

He had put the book there weeks since, knowing that the reward was inevitable. Cephas Frake was now laboring for the union of workhouses of St. Gwynn-by-Godolphin, Gwynnford, Clegg, and Squillante parishes. The boy knew that Parmley had arranged for his father to work through the

parish, yet the father would not tell his son where he was laboring on any given day. The boy had asked the parson, bluntly, in private, a number of times over the past year, why his father was so secretive, but Parmley could offer no explanation that would not exacerbate the boy’s unhappy domestic situation. Cephas Frake, he knew, was ashamed that his circumstances were so desperate that he was forced to plead pauperism in order to feed his family.

Parmley propped the book up against others on his desk, and let the map dangle as he stood by it. Jack Frake gripped the edges of his bench and stared at the colored phenomenon. The parson pointed with his finger to a cream-colored shape that resembled a ragged leg of mutton. “This is our land,” he said, “our

island

. England.” His finger moved to rest on one tiny area at the very bottom of the mutton leg close to a vast expanse of green. “And here we are. England is composed of numerous counties. We reside here, in

Cornwall

. A very lonely, but somewhat attractive county it is. This is the English Channel.” The finger then moved to rest on one of the innumerable, tiny, finely printed names that filled the space. “And here is where we live, in the parish of St. Gwynn-by-Godolphin. Godolphin, as you must know, is the name of the quite modest river that flows through Pendyn Valley to Gwynnford and the Channel — and was, coincidentally, the name of the late Queen Anne’s unfortunate lord treasurer. Our —

your

ancestors long ago gave it that name because some fishermen reported having seen dolphins frolicking in the estuary there.

The river that goes to the dolphins

. Do you see?”

Jack Frake nodded.

“And even longer ago, a monk named Gwynn lived in a hut somewhere near the river. He was a holy man, recognized by our church, the Anglican Church, who helped travelers cross the river. Thus, Gwynnford, a town perhaps a century older than our own St. Gwynn. Being directly on the Channel, the town is some miles removed from St. Gwynn’s original domicile. Gwynnford has seen better days,” he added with disapproval, thinking of the taverns and sailors’ hostelries that lined the little port’s main street, and of the good-natured but unpleasant rough-housing he had received there at the hands of some its

habitués

.

Jack Frake glanced up, expecting more.

Parmley felt an inner glow, and smiled. “Here is your home,” he continued, moving his finger west along the coast. “Trelowe.

Its

etymology is deceptively obvious, yet more than likely spurious. Perhaps it was so called

after the stunted oaks that grow near your commons, but there are other, equally convincing apocryphal explanations. And to the east of St. Gwynn, the villages of Pondwrinkle and Clegg. South and east of us, Gwynnford. North of Trelowe, the village of Squillante. Ah, and here is Treethick! A great forest once stood in its fields. The farmers, I hear, still break their ploughs on the ancient stumps that are still in the soil. And close by it, Marvel.” He paused. “It is said that Marvel is the secret headquarters of that scoundrel, Augustus Skelly.” Parmley paused again to frown at the boy. “Have you ever seen smugglers, Mr. Frake?”

The boy shook his head. It was true. He had only heard of the smugglers. They were phantoms who moved in the night, as mysterious and frightening as the fantastic creatures his mother threatened him with if he did not obey. He had heard his parents and other adults in Trelowe talk in whispers among themselves about Augustus Skelly. Skelly and his men, they said, hanged customs officers and informers, and kidnapped children whom they fed to sea monsters so that the monsters would not molest the gang’s smuggling boats. But, as with the ogres and goblins in his mother’s arsenal of terror, he had never seen a Skelly man.