Jack the Ripper: The Secret Police Files (35 page)

Read Jack the Ripper: The Secret Police Files Online

Authors: Trevor Marriott

It should be noted that the post-mortem was not carried out till some 12 hours had elapsed from the time of the murder. In that time lividity and rigor mortis would have set in. Lividity is where the blood sinks to the bottom of the body due to death. This would affect the visible physical structure of the body. That would mean that cuts and wounds after a long period of time would look less fierce and with the skin hardening may not be so readily visible.

We cannot say what happened to the body after the post-mortem, was it left lying in the coffin, or was it propped standing up and left for a lengthy period of time. As far as the photographs are concerned and the different ones in the public domain it may have been the case that more than one photographer was involved in taking different photographs at different times.

The black and white photographs of Eddowes are copies of the originals but of course I have to ask the question what happened to the originals? It would seem that they must have been in the possession of the City of London Police in 1968 for the copies to be taken but what happened to them after that? Did they get lost or thrown out? I doubt this. Were they borrowed and simply not returned by a police officer in similar circumstances to that of Commander Millen as described above, or were they simply stolen and now sit hidden away in a Ripperologist’s own private collection?

It is a fact there are a number of important documents and records and photographs which have supposedly “gone missing” over the years most since the 1960s/1970s at a period in time when original documents were freely available in the archives for people to go and examine unsupervised. What happened to them? They all didn’t just vanish into thin air. The answer is they were stolen and perhaps now sit in a Ripperologist’s private collection never to see the light of day again, thus depriving the world of vital information which may lead to the identity of the killer or killers.

As far as other similar facial mutilations carried out on any of the other victims there appear to have been none, except for Mary Kelly, but her face was mutilated to the point she was almost unrecognizable, and of course there is a doubt about her actually being a Ripper victim. It is also documented that other alleged Ripper victims were found with cuts and lacerations to their bodies. Sadly these were never photographed so there is no way of telling if any of these cuts or lacerations were in the shape of X’s.

It is quite possible that potentially there could be a direct link between the information provided by De La Ree Bott, Les XX, Whitechapel, and ultimately the Whitechapel murders. But was it just a tenuous link or something more sinister, and could I find any more direct or corroborative evidence to support the new findings?

Throughout my police service I learnt to check and recheck evidence and information when dealing with undetected crimes. This proved invaluable in the case of Eddowes in discovering the X’s carved on her cheeks. It would also prove to be invaluable with regards to uncovering further evidence in the murder of Carrie Brown the prostitute who was murdered in a hotel room in New York on April 24th 1891. It has been suggested that she could also have been a Ripper victim a suggestion that I concur with having regard to my previous investigation into Carl Feigenbaum and the belief that he murdered women both in Whitechapel as well as Germany and the USA.

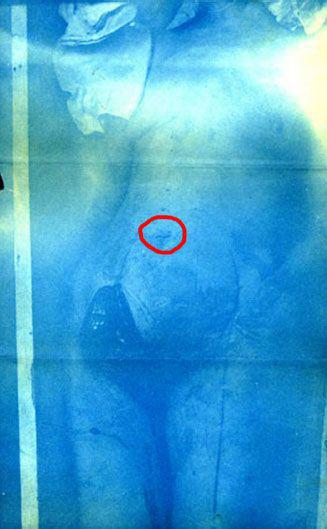

I then went back and re-examined the mortuary photos taken of Brown’s body (Pictures 13-14) the first photo was taken with the body lying face down. On her buttocks can clearly be seen a large X which has been carved in the skin. Looking at the second photo which was taken with the body lying face up there is what I would suggest is a very small X which appears to have been carved into the abdominal area. I have blown the photo up but that doesn’t make it much clearer. This X is of a similar size to the X’s seen on the face of Eddowes. If it is a second X then this is clear proof, which may directly link these murders to the same killer. This new evidence may also add further weight to the belief officers had that Mary Kelly was not killed by the same hand as the other victims. As is known Kelly was murdered and her body butchered in the confines of her locked room. Carrie Brown was also murdered in the confines of a locked room giving her killer the time and the opportunity to butcher her body and remove any organs, this did not happen. In the absence of this it is another piece of the jigsaw, which supports the theory that Feigenbaum may have committed murders in three different countries as I have suggested. It also could now suggest that the same killer was not responsible for all of the Whitechapel murders.

After assessing and evaluating the new information regarding Les XX and the Whitechapel murders, it would be wrong to totally rule out Les XX from any involvement in one, some, or all of the murders. I have to also refer to the long and expensive investigation conducted by the famous crime novelist Patricia Cornwell. She believes that Walter Sickert was involved in the Whitechapel murders. I have already documented that Sickert was closely connected to Les XX, so her beliefs may not be as wide of the mark as Ripperologist’s readily suggest.

However, the fact that there now could be a direct link between Carrie Brown’s murder in New York and Eddowes’ in London perhaps weakens that theory. It once again opens up the Ripper mystery and yet again throws up more questions than answers.

CHAPTER TEN

THE SECRET POLICE FILES

For many years researchers have referred to missing police files, which may or may not have contained other information in relation to the Ripper investigation of 1888. There was no specific information as to what these files were or where they had been originally located, or for that matter did they ever actually exist.

Through my investigation I discovered that in fact there were still in existence unreleased Metropolitan Police records dating back to 1888. These had apparently been retained in the Metropolitan Police Special Branch archives, and due to the sensitive nature of the contents had not openly been made public. It has already been documented that at the time of the Whitechapel murders the police not only had their hands full with the Ripper investigation but had major investigations ongoing at that time into the activities of Fenian terrorists and other anarchists who were operating in London at this time, all seeking to disrupt the forces of law and order. In this current context the term anarchist is defined as:

“One who occupies himself with the means of giving effect by physical force, if need be, to some such theory as mentioned above, and includes the plotting against the lives of Crowned Heads, Heads of States, or other highly-placed persons, and advocating their assassination.”

Special Branch was first formed in January 1888 and Chief Inspector John Littlechild was head of a team of specially selected officers. In 1913 Littlechild suggested that a suspect for the Whitechapel murders could have in fact been the American quack, Doctor Francis Tumblety. Ripper researchers in recent years have suggested Tumblety was under surveillance by Special Branch in relation to his possible involvement with the Fenians at that time.

I was intrigued to find out what these police records were and what they may contain. Enquiries with the Metropolitan Police revealed that in fact the records in question were in fact ledgers and a register, which contained direct references to specific files relative to each entry. They are documented as follows:

Chief constables CID Register “Special Branch” (1888-1892)

Metropolitan Police Ledgers “Special Account” Vol 1-3 (1888-1912)

The next step was to try to gain access to these ledgers and the register. Enquiries revealed that they were in fact still held in the Special Branch archives at New Scotland Yard. I made various Freedom of Information requests to access them, but I was informed that access to them had now been closed pending a Freedom of Information Act appeal, which had been lodged back in 2007 by Alex Butterworth a historical researcher who was conducting research into the early years of Special Branch. I was informed that this appeal hearing was due to take place in February 2009.

In the interim period I also ascertained that in fact these ledgers and register had been freely available to bona fide researchers and historians for viewing up until 2008, and in fact some historians and researchers not connected to the Ripper investigation had previously examined them and in one case prior to the new restrictions being imposed one such historical researcher Dr. Lindsay Clutterbuck, a former Metropolitan Special Branch officer had in fact published in 2002 a 450 page thesis, which contained detailed information and extracts from the register and the ledgers. His thesis was titled, “

An accident in history? The evolution of counter terrorism methodology, in the Metropolitan Police from 1829 to 1901”

.

More recently the Metropolitan Police had refused open and unrestricted access, and formulated an undertaking in relation to these ledgers whereby any researcher wanting to examine the documents had been required to sign this undertaking stating that they would not publish or disclose the contents of either the register or the ledgers. Although not having access to these ledgers and the register at this time my enquiries revealed that in fact as previously stated that they were not specific files. The special account ledger apparently showed entries involving outgoing expenditure including payments made to informants who had been used by Metropolitan Police Special Branch officers throughout the various years which they refer to.

Clutterbuck states that the chief constable’s register was made up of alphabetical entries relating to information given by informants and also general information fed into the system by police officers. All of the entries related to specific files on each topic and had file reference numbers. All the information gathered had been systematically collated, categorized and then stored in box files for future reference.

However, according to Special Branch the specific files referred to had apparently not been retained and destroyed. The police of course do have the option of destroying any files they think fit in the interests of national security, either due to the passage of time, or following the conclusion of a particular case to protect the identity of an informant. Sadly all that was apparently left were the ledgers and the register. The question was did they contain any new information regarding Jack the Ripper and the Whitechapel murders?

I was also curious to find out why these files having been originally opened to the bona fide researchers had suddenly been closed and was now the subject of a Freedom of Information appeal. The answer soon became apparent.

A researcher by the name of Felicity Lowde who had an interest in the Whitechapel murders had been allowed to view the register and ledgers in 2005 but despite signing the undertaking she had apparently photographed some of the pages from these ledgers and the register, which she then published on her own blog on the Internet along with other information from these documents.

It was then suggested that the police took action against Ms. Lowde by seizing her computer’s hard drive and taking action to seek an injunction order against her in the High Court. Further enquiries however revealed that in fact this seizure was in connection with an unrelated criminal matter. The said information and photos and photos of extracts from both sets of records are still to this day visible on her web blog. I will discuss them in more detail in due course.

As these ledgers and the register contained details of informants the Metropolitan Police were concerned that some of these named informants may still have living relatives and it was important for their details to be kept secret and for any living relatives to be offered protection despite the passage of time. The practice of protecting the identity of informants is still the case even today, although it should be said that even from my time as a serving detective officer most informants were referred to either by nicknames or by simply using false names.

In the fight against crime and terrorism informants are a valuable asset to a detective officer more so than ever in the early days before modern technology was an aid to criminal detection. It should also be noted that informants are usually only paid on information they provide and that information must be of a positive nature However, there are certain circumstances where there are exceptions to that rule which I will expand upon later.