Jackie and Campy (2 page)

2.

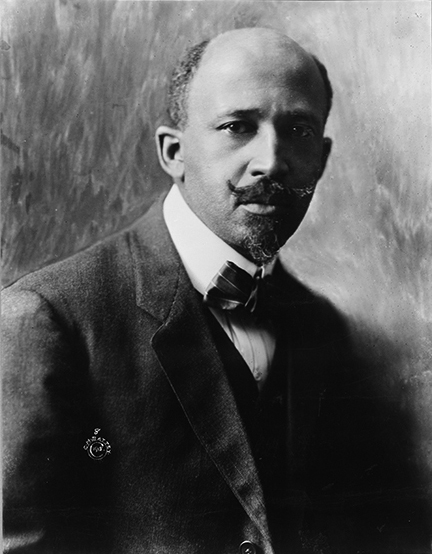

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois, the first black to receive a PhD at Harvard, pro- moted integration of the races and full citizenship for blacks. In 1905 he organized the Niagara movement to demand an end to racial discrimination in education, public ac- commodations, voting, and employment. Du Bois’s philosophy of direct action placed him at odds with Booker T. Washington but inspired the black activists who came of age during World War II. (Library of Congress)

As the twentieth century unfolded, Washington became regarded by blacks as an Uncle Tom for his accommodationist philosophy. Du Bois, on the other hand, lost faith in integration and by the 1940s began to advocate a form of black self-segregation that led to his dismissal from the

NAACP

. Increasingly disillusioned with American society, he joined the Communist Party, renounced his U.S. citizenship, and joined the African nationalist leader Kwame Nkrumah in Ghana.

22

The two men’s opposing philosophies inevitably created a permanent tension within the black community over the means of achieving full equality. The resulting dialectic embodied a contrast between self-reliance and direct action that was reflected in the movement to integrate Major League Baseball in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Although there is no documentary evidence to indicate that either Jackie Robinson or Roy Campanella was familiar with the specific philosophies of Du Bois or Washington, both ballplayers were acutely aware of the conflicting approaches to civil rights. That conflict was an inextricable part of the cultural currency of ideas that circulated within the African American community during the mid-twentieth century. Each man embraced a specific part of the dialectic in the movement to integrate Major League Baseball. Robinson thought that integration could be achieved only by challenging directly the segregated society in which he lived. Like Du Bois, he believed that racial discrimination attacked his manhood, and he protested, sometimes subtly, sometimes antagonistically. For Campanella, integration could be achieved only through a quiet self-reliance in which he could prove to whites that he was just as

talented, just as able as they were. Like Washington, Campanella sought to better his economic circumstances in the hope of someday improving his social condition. In each case, the goal was the same, but the means were as different as fire and ice.

Many writers have explored Robinson’s personal odyssey in breaking baseball’s color barrier in the broader social and historical contexts of the civil rights movement. The most notable books are Jules Tygiel’s

Baseball’s Great Experiment

(1983), David Falkner’s

Great Time Coming

(1995), and Arnold Rampersad’s biography,

Jackie Robinson

(1997). While these accounts offer a more comprehensive understanding of Robinson’s significance to the larger civil rights movement, none of the authors explores in depth the fundamental dialectic that emerged within the movement at the turn of the twentieth century and how it influenced modern baseball’s first black player. Few authors, by comparison, have examined Campanella’s role in integrating baseball or his personal conflict with Robinson. Those who have addressed the relationship either tend to marginalize the feud or deny it altogether.

23

Only by examining the dialectic, however, can historians gain a better understanding of the important roles Robinson and Campanella played in the integration of baseball.

Jackie and Campy

goes beyond the existing accounts by examining the relationship of these black Dodgers stars in the broader context of the modern civil rights movement and the dialectic that defined their competing approaches to integrating the game. It is not an attempt to examine the storied history of the Brooklyn Dodgers of the 1950s or their rivalries with the New York Giants and Yankees. Nor does the book pretend to be a comprehensive biography of Robinson or Campanella. Readers interested in those topics can find many other books that are more suitable. Instead

Jackie and Campy

offers an important corrective to what has become a sanitized retelling of their relationship and its impact on baseball’s integration process. I begin with the lackluster early history of the Dodgers and establish the social context of the story by describing the changing demographics of Brooklyn during the first half of the twentieth century. Ebbets Field became a melting pot for European immigrants, their children, and blacks. Brooklynites subordinated their social differences to root for the Dodgers. In the process they created an ideal setting for baseball’s noble experiment with integration.

Dodgers president Branch Rickey, a visionary with a strong Christian ethic, tapped into the existing pool of talent in the Negro Leagues to break the so-called gentleman’s agreement among club owners that prohibited signing black players. He was aided in his quest for integration by a perfect storm of forces: the popularity of Negro League Baseball among both black and white fans, suggesting that the integration of the Majors would be a lucrative enterprise; a younger generation of African American veterans who had served in World War II and desired greater political, social, and economic opportunities; and the receptiveness to integration of a new baseball commissioner.

Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella were the first two black players selected by Rickey. No two individuals could have been more different in their background, personality, and approach to civil rights. Robinson was the son of a southern sharecropper who deserted his family. Raised by a God-fearing mother and his four older siblings in Pasadena, Jackie learned at an early age to strike back against the racial injustices he experienced. He channeled his frustration with Jim Crow into sports and became an outstanding college athlete. When the United States entered World War II, he served as a second lieutenant and challenged the segregated policies of the military. Threatened with a court-martial for refusing to sit in the back of an army bus, Robinson was honorably discharged. He joined the Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro Leagues, where Dodgers scouts discovered his talent. Rickey was immediately impressed by Jackie’s outstanding athletic ability, competitive fire, and courage. These special qualities, along with Robinson’s college and military experiences, convinced the Dodgers’ president to select him for his experiment in integration rather than a more established Negro League star.

Campanella was also a product of the environment in which he was raised, but unlike Robinson, he enjoyed a stable home life as a youngster. He was the son of a black mother and an Italian father who sold fruits and vegetables on the streets of Philadelphia. The happy-go-lucky teenager quit high school to begin his professional career with the Baltimore Elite Giants. He soon challenged Josh Gibson as the dominant catcher of the Negro Leagues. During World War II, Campy, who as the married father of two children was exempt from military duty, completed his alternative service on an assembly line making steel plates for army tanks

and managed to continue his playing career. After the war the Dodgers scouted the power-hitting catcher. Attracted by Campy’s exceptional playing ability, leadership, and boyish enthusiasm for the game, Rickey seriously considered him as a candidate to break the color line but ultimately made him his second choice.

The year 1947 was pivotal for both players. Robinson broke Major League Baseball’s color barrier and did so with a dignity and restraint never seen before or since in the sports world. While opposing players spiked him on the base paths and showered him with racial obscenities, opposing fans mailed him death threats. Through it all, Jackie persevered, channeling his anger into his on-field performance. In the process he brought the Negro Leagues’ electrifying style of play to the Majors and quickly became baseball’s top drawing card. Meanwhile Campanella distinguished himself as a catcher in the Dodgers farm system at Nashua, New Hampshire, where he proved that a black man did indeed possess the intelligence and physical ability to lead a professional baseball team. His leadership would become indispensable to the success of the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1950s.

In the spring of 1948 Jackie and Campy were united in Brooklyn. As the only black Dodgers, they established a mutual support system on and off the field. But the following year their bond began to deteriorate, after Rickey removed the “no striking back” ban on his star second baseman. Jackie, now free to express himself, became increasingly combative. On the field he taunted opponents and antagonized umpires. Off the field he was an outspoken advocate of civil rights, voicing his sentiments to the House Un-American Activities Committee, which was holding hearings on the Communist infiltration of American minority groups.

After repeated attempts to discourage his friend’s controversial behavior, Campanella began to distance himself from Robinson. The breaking point in their friendship came after the 1949 season, when the two teammates went on a barnstorming tour through the South. A disagreement over Campy’s financial compensation and Robinson’s unwillingness to rectify the situation irreparably damaged the relationship.

During the next seven years Robinson and Campanella struggled to keep their personal conflict in check so it would not interfere with the positive team chemistry that was essential to the Dodgers’ success in the

1950s. Robinson was increasingly antagonistic toward baseball’s white power structure and press and unapologetic about using his status as a star athlete to further the cause of civil rights whenever possible. His proactive approach against racial discrimination—both perceived and real—placed him on an inevitable collision course with Campanella, who refused to engage in racial politics; he led by example, believing that his on-field performance would do more for other black players than controversial remarks or protests.

Contrary to popular belief, Robinson and Campanella had very little in common aside from race and baseball. While both individuals mentored younger African American teammates, their different approaches to civil rights created tension among those same players. Fortunately for the Dodgers, Campanella and Robinson suppressed their differences on the playing field, allowing the team to capture their only World Series championship in 1955. But when Jackie retired after the 1956 season, he publicly criticized Campanella for his refusal to protest racial discrimination. Campy was quick to return the criticism, and the two men were estranged for nearly a decade.

Jackie and Campy

is a very human as well as necessary account of the complicated relationship between Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella. The book does not detract from either man’s historic achievement as a pioneer in the struggle to integrate the national pastime as much as enhance the humanness of these baseball icons. More important, their examples reveal that public defiance is just as important as self-reliance in bearing witness against social injustice. While Robinson and Campanella may not have realized that essential truth, their conflict can serve as a meaningful lesson for others who hope to make a constructive contribution to race relations in our country. It is in that spirit that this book was written.

1.

Brooklyn’s Bums

On Saturday, April 5, 1913, Brooklyn was buzzing with excitement. Newspaper boys, tavern keepers, politicians, and ordinary people were all promoting or talking about the premiere that afternoon of the borough’s brand-new ballpark, Ebbets Field. A preseason exhibition game was scheduled between the hometown Dodgers and the New York Yankees, cross-town rivals who would eventually become regulars in the annual fall classic known as the World Series. More than a thousand early birds had arrived by noon, crowding the main entrance behind home plate, though the pregame ceremonies were not scheduled to begin until three o’clock. As they waited patiently for the gates to open, the fans couldn’t help but be impressed by the architectural grandeur that surrounded them.

1

Located in Flatbush, just east of Prospect Park on a plot bounded by Montgomery Street, Bedford Avenue, Sullivan Place, and Cedar Place, Ebbets was, in accordance with the latest technology, a concrete-and-steel structure with a seating capacity of twenty-five thousand. The exterior façade of the ballpark was captivating. A row of fourteen small-pane, Federal-style windows separated by brick pilasters ran just above the main entrance to the top of the building’s crown. Above these the words “Ebbets Field,” in full caps, were mounted on the façade’s setback. Below the windows was a galvanized-iron, glass-glazed marquis that ran fifty-six feet above the main entrance. Beyond were three curved doors that recessed into the wall on either side when the gates were opened. This majestic façade would come to define the ballpark in the national psyche for generations to come.

Inside the main entrance was a semicircular rotunda, the most ornate element of the ballpark. It contained a circular room, eighty feet in diameter, with Italian marble columns and a marble mosaic tile floor patterned after the circular stitching on a baseball. Fourteen gilded-cage ticket windows were located along the circular walls. Each window had adjacent doors and a turnstile behind it to efficiently control the flow of fans into the ballpark’s grandstands. The ceiling was elliptical and reached a height of twenty-seven feet at the center. The most charming element of the rotunda, however, was a magnificent chandelier with twelve facsimile bats suspending illuminated glass baseball globes.

2

3.

Brooklyn’s Ebbets Field, opened on April 5, 1913, was among the first concrete-and- steel ballparks. The park eventually became famous for its circus-like atmosphere and the hapless play of the hometown Dodgers, more affectionately known as “dem Bums.” (National Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, New York)

Anyone who entered the ballpark that day must have been awed not only by the impressive surroundings but by the fact that Dodgers owner Charles Ebbets, an infamous penny-pincher, had spent his money so extravagantly. At a cost of $750,000, the project was a huge financial risk, one that forced Ebbets to take his contractors, Stephen and Edward McKeever, as partners. He realized that the success of his franchise depended not only on building a winning team but on constructing a larger, more

permanent ballpark than the rickety old bandbox the Dodgers had called home for most of the past three decades. Ebbets risked his fortune on a hunch that the new ballpark would attract fans on a routine basis at a time when interest in baseball was growing across the nation. Besides, Flatbush was an ideal location, just a few miles from the Brooklyn Bridge and near more than a dozen transit lines. Ebbets predicted that those advantages would translate into a handsome return on his investment.

3

If the pregame activity was any indication of the future, Ebbets had good reason to be optimistic. Eager fans jammed inside the Rotunda as game time neared. Designed to provide fans with shelter from the rain and a comfortable place to meet before the game or linger after it, the Rotunda on this day became a maelstrom of excitement, tension, and frustration. Incoming hordes pressed against those who had already purchased tickets, eliciting profane and colorful language. A few women were the victims of unsolicited pinches, and reports of pickpockets kept the police busy.

By 1:30 p.m., most of the seats in the grandstands and bleachers were occupied, and the bluff across Montgomery Street behind the left-center-field fence was packed with onlookers up to the corner at Bedford Avenue. While the fans settled in to the music of Shannon’s 23rd Regimental Band, they were struck by the intimacy of the new ballpark.

4

Its covered double-deck grandstand, which began in right-field foul territory and wrapped around the diamond to just past third base, hugged the infield, allowing fans to interact with the players. On the third base side, the grandstand went only forty feet past the infield, and uncovered single-decked bleacher seats extended the rest of the way to the left-field foul pole. The fences were 9 feet high across the outfield, and the dimensions were 417 feet from home plate down the left-field foul line, 477 feet to dead center, and 301 feet down the right-field foul line. Unless you were a left-handed hitter, those were formidable distances. Predictably Ebbets Field would come to be known as a “pitcher’s park.”

5

Fans were also impressed by such innovations as a scoreboard that displayed not only line scores of out-of-town games but who was up in the batting order, and a microphone situated near home plate so balls and strikes could be heard throughout the ballpark.

6

Shortly after three o’clock, Charley Ebbets accompanied Edward McKeever and his wife, Jennie, out to center field to begin the ceremonies. The

players of both teams, dressed in their eight-button sweaters and with arms folded or hands behind their backs, stood behind the threesome as Jennie McKeever slowly hoisted Old Glory with an occasional pause for photographs. After the flag was raised, dignitaries, fans, and ballplayers removed their hats and the band played the national anthem. Ebbets assigned the honor of the ceremonial first pitch to his twenty-year-old daughter, Genevieve, who threw a perfect strike to umpire Bob Emslie. Then, to the roar of the crowd, the Brooklyn Dodgers took the field.

Dodgers ace Nap Rucker retired the Yankees in order in the first. In the bottom of the inning, Brooklyn second baseman George Cutshaw, batting second, singled up the middle for the first hit in Ebbets Field. Later that same inning, Zack Wheat provoked the first humorous blunder in the ballpark’s long and storied comic tradition. Lofting a foul pop-up in third-base foul territory, Wheat stood and watched as Roy Hartzell, the Yankees’ third baseman, took a headfirst dive into a group of band members, hitting his head on the bass drum. Fans laughed uproariously as the sound resonated throughout the ballpark and, true to form, unmercifully razzed the infielder for the remainder of the game.

Casey Stengel, the Dodgers’ lead-off hitter, scored the first run in the fifth when he hit a long, hard line drive to left-center. Yankee center fielder Harry Wolter tried to cut it off, but as he reached for the ball he inadvertently kicked it. As the ball rolled to the wall, Casey scampered around the bases for an inside-the-park home run. The following inning, Jake Daubert replicated the feat, once again hitting a hard liner in Wolter’s vicinity. Although the Yankees tied the game with a couple of runs in the top of the ninth, the Dodgers prevailed in the bottom of the inning when Red Smith singled in Wheat from third base, capping the 3–2 Brooklyn victory.

7

“Rejoice, ye fans,” urged the

Brooklyn Daily Eagle

, “and deliver thanks for Charles Hercules Ebbets’ magnificent stadium, the greatest ballpark in these United States,” dedicated in the presence of “25,000 wildly enthusiastic rooters and at least 7,000 others who witnessed the 3–2 trouncing of Frank Chance’s Yankees from the bluffs that overlook the field.”

8

The

Brooklyn Daily Standard Union

compared the new ballpark to the temples of ancient Rome and predicted that Ebbets Field would “last 200 years, or four times as long as the average structure.” Pointing out that there was no apostrophe on the name “Ebbets Field” above the main entrance, the

newspaper explained that while the “huge amphitheater is named after the man who built it,” the ballpark is “really dedicated to the fans and the Brooklyn team.”

9

Those last words were prophetic.

The history of Ebbets Field reflects the love affair between the Dodgers and their blue-collar fans. The losing tradition that unfolded there actually endeared the team to Brooklynites, who affectionately referred to the Dodgers as “dem Bums.” Just as important was the comedic way the team lost: outfielders colliding in pursuit of a fly ball, wacky miscues on the base paths, and players forgetting the number of outs in an inning, leading to even more blunders. The comedy of errors made the team lovable because it reminded the fans of their own humanness. Essentially Brooklyn’s fans embraced the Dodgers because cheering for the team was like rooting for themselves. In the process the fans discovered common ground with each other, especially after Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947. Baseball became the great equalizer, the one institution that allowed everyone to stand on equal footing, regardless of race or ethnicity. Ebbets Field became a melting pot for an ethnically diverse, racially mixed community. In fact Brooklyn was ready for the integration of baseball by the mid-1940s because the Dodgers and their ballpark were at the center of demographic trends and prevailing notions about ethnicity and race that allowed baseball to break its infamous color barrier. Ultimately Ebbets Field, the Dodgers, and their fans served as powerful catalysts for social change, playing a pivotal role in the integration of the national pastime.

Brooklyn’s love affair with the Dodgers began on May 9, 1883, when a thousand or so fans turned out to watch their predecessors, the Brooklyn Polka Dots, defeat Harrisburg, 7–1, near Prospect Park. Known for their flashy, polka-dot hosiery, the team chalked up a second victory, 13–6, three days later against Trenton at their brand-new home, Washington Park. Situated in a hollowed-out basin some twenty-five feet below street level at Third Street and Fourth Avenue in the Red Hook section of the city, the ballpark sported a single-tier wooden grandstand along with bleachers to accommodate as many as two thousand spectators. The Polka Dots were owned and operated by real estate dealer Charles H. Byrne and his Manhattan gambling house partner, Joseph J. Doyle. Hoping to achieve greater respectability, Byrne arranged for his amateur club to join the American Association the following season. In 1887, when six of the

players got married, the Polka Dots changed their name to the Brooklyn Bridegrooms, popularly called the “Grooms.”

10

After capturing the American Association pennant in 1889, the Grooms traveled across the East River to Manhattan to play the National League’s Giants for bragging rights as the “best team in baseball.” Although the Giants prevailed in the best-of-eleven-game series, six games to three, owner John Day proved to be a sore winner. “We will never play your team again,” Day said to Byrne. “Your players are dirty. They constantly stall and complain. We’ve been deprived of three games by trickery,” he complained, referring to Brooklyn’s repeated attempts to stall and have the game called for darkness once they held a lead. “I don’t mind losing games on their merits,” Day added, “but I do mind being robbed of them.”

11

Unfortunately for Day, Brooklyn jumped to the National League in 1890, and the acrimonious rivalry between the two New York teams was born. It was part of a larger competition with Manhattan that came to define Brooklyn’s idiosyncratic culture.

Located on the southwestern tip of Long Island and situated on New York harbor across the East River from Manhattan, Brooklyn, Kings County, was once an independent municipality and, during the second half of the nineteenth century, the third largest city in the nation. The population of 396,099 in 1870 was exceeded only by the populations of New York City and Philadelphia. The other towns of Kings County were largely rural, with a combined population of less than 12,500. Gradually those nearest Brooklyn became annexed to it, including Flatlands, New Utrecht, Gravesend, Jamaica Bay, and Williamsburg. The steam railway and elevated train linked these towns to Brooklyn, making the downtown accessible to the growing population. As the 1880s unfolded, the working class and immigrants took up residence in the neighborhoods of the annexed area (called the Eastern District), most notably the German and Irish. Many of these residents formed the backbone of labor for the booming industries that dominated the waterfront of the Eastern District, including shipbuilding, grain storage, sugar refining, and glass manufacturing.

12

The completion of the Brooklyn Bridge in 1883 established the first physical link between the nation’s largest and third largest cities. It also symbolized the end of Brooklyn’s independence as well as an impending political union with New York City. By 1898 unabated economic and

demographic growth pushed Brooklyn to the limit of its allowable state debt and almost exhausted its ability to issue bonds. Republican reformers, realizing that Brooklyn’s economic and political future was tied to New York City, defeated the Democratic machine, long in control of local government, and moved toward consolidation. On January 1, 1898, Brooklyn combined with Manhattan and the boroughs of Queens, Staten Island, and the Bronx to create modern-day New York City.

13

Brooklyn was now a borough and would eventually become the poor stepchild of the more refined Manhattan.