Japan's Comfort Women (12 page)

Read Japan's Comfort Women Online

Authors: Yuki Tanaka

Tags: #Social Science, #Ethnic Studies, #General

Among the army units stationed in areas in which “hostile districts” were located, it seems that some commanders set up comfort stations without higher official approval. In such cases, comfort women were civilian girls who were forcibly separated from their families, detained in military compounds for a certain period (up to six months), and continuously raped by Japanese soldiers, and, in some cases, by their Chinese collaborators as well.

A recent survey conducted by a local school teacher, Zhang Shuangbing, in Yu prefecture, Shanxi Province, disclosed that some 50 women have so far been identified as victims of this sexual crime in this prefecture. However, about 30 of them have died since they revealed their past as comfort women. The majority of these victims were young unmarried women between 15 and 18 years old at the time. One girl called Qiaolian was 13 years old.43

Li Xiumei was 15 years old when she was abducted by four Japanese soldiers from her home in a small village called Lizhuang, in Yu prefecture in September 1942. At the time, her mother was also at home but could not stop the Japanese men taking her daughter away. Li was taken to a village called Jingui, where a small detachment unit of the 14th Battalion had its garrison compound.

Together with two other girls she was detained in a dwelling cave, which is quite a common feature in this region. Day after day they were raped by Japanese soldiers in the cave. Each day she was raped by at least two or three soldiers; sometimes by 10 soldiers. The cave was guarded by Chinese collaborators, making it impossible to escape. She was often taken to an officer’s room in the fortress and raped there, too.44

One day, about five months after she had been abducted, she tried to refuse the commander who had been particularly wild in his treatment of the girls. He severely beat her with his waist belt. Her right eye was hit hard with the buckle, resulting in her losing the sight of that eye. When she continued to resist the officer, he clubbed her, knocking her to the ground. Later she was sent back

Procurement of women and their lives

47

home because her injuries made her physically unable to serve the Japanese men. However, on her return she found that her mother had committed suicide and her father gone mad. It appears that in order to get their daughter back, the family had paid the Japanese troops a ransom of 600 yuan, a large sum of money at the time. They had raised the money by borrowing from relatives.

When they were told that it was not enough to secure her release, the mother hanged herself. The husband became insane with the shock of his wife’s death.45

In her testimony, Liu Mianhuan – another victim of sexual violence committed by the same detachment unit stationed in Jingui – describes being taken from her parents in March 1941 by three Chinese collaborators. She too was detained in a dwelling cave and raped by the three Chinese before being taken to the Japanese commander. For the following 40 days she was raped by the commander at night and by Chinese collaborators and Japanese soldiers during daytime. It is not certain whether the Japanese commander who violated Liu Mianhuan was the same man who victimized Li Xiumei. Eventually Liu Mianhuan became too sick to be exploited by the Japanese. She was released in return for a 100 yuan ransom, which her father managed to raise, borrowing from relatives and friends.46 “Sexual slavery hostages” rather than “comfort women” is a more appropriate term to describe the circumstances endured by Li and Liu. (Incidentally, the 14th Battalion which was responsible for the crimes committed against these Chinese girls was transferred to Okinawa in August 1944. Almost all perished in the Battle of Okinawa in 1945.) When we closely examine the testimonies of the former Filipina comfort women, we note similarities between the procurement methods used in China and in the Philippines.

Several official documents which refer to comfort stations in the Philippines have been found in archives in Japan and the US. According to one of these documents, in Manila alone, in early 1943, there were 17 comfort stations for the rank-and-file soldiers, “staffed” by a total of 1,064 comfort women. In addition, there were four officers’ clubs served by more than 120 women. No information is available as to the nationality of these comfort women. Other documents reveal the fact that comfort stations were also located at Iloilo on Panay Island, Butsuan and Cagayan de Oro on Mindanao Island, Masbate on Masbate Island, and Ormoc and Tacloban on Leyte Island.47 It is almost certain that there were comfort stations at many other places in the Philippines. These documents do not disclose much information about the comfort women, but a few, such as those referring to comfort stations in Iloilo, mention a number of Filipina comfort women, including several girls between 16 and 20 years old.48 It is almost impossible to know from the archival documents how these women were “recruited”

and under what conditions they were forced to serve the Japanese troops.

It was in 1992, almost half a century after the end of the war, that the truly horrific picture of widespread sexual violence against Filipinas during the occupation first emerged. This was made possible when Maria Rosa Henson cour-ageously came forward and revealed her painful past as a comfort woman.49

Encouraged by her action, many women spoke out – one after another – and

48

Procurement of women and their lives

gave detailed testimonies about their wartime ordeals. Eventually, the testimonies of 51 women were collected by a group of Japanese lawyers and a local NGO called the Task Force on Filipino Comfort Women.50

In contrast to the military authorities’ behind-the-scenes approach in Korea, Taiwan, and the Dutch East Indies, available testimonies, including that of Maria Rosa Henson, indicate that at many places in the Philippines the Japanese troops directly secured comfort women. Furthermore, their methods were wanton. They included abduction, rape, and continuous confinement for the purposes of sexual exploitation – similar to the Chinese case we have already examined. Both in China and the Philippines, it seems that the Japanese did not even try to conceal what they were doing to the civilians.

The main reason for such direct action by the Japanese troops in the Philippines may lie in the fact that the anti-Japanese guerilla movement was strong and widespread throughout the occupation period, as in “liberated districts” in China.

It is said that there were more than 100 guerilla organizations at the peak, involv-ing about 270,000 activists and associates.51 Hukbalahap, which Maria Rosa Henson joined, was one of the largest of these guerilla organizations. It was comprised predominantly of peasants and workers under the influence of the Communist Party. As a result of this strong anti-Japanese movement, the Japanese were able

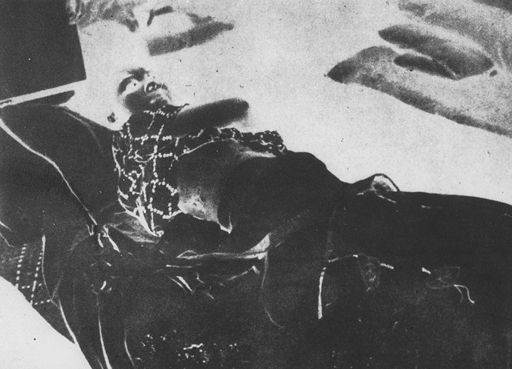

Plate 2.4

A Filipina girl, who was stabbed with a bayonet by a Japanese soldier because she tried to fight off being raped, lying on a hospital bed. The date and exact location are unknown.

Source

:

i

tsuki Shoten

Procurement of women and their lives

49

to control only 30 percent of the Philippines.52 Guerilla activities were particularly strong on Luzon and Panay. The fact that the majority of the people who have so far been identified as former comfort women were residents of these two islands also suggests the close link between Japanese sexual violence against civilians and the strength of popular guerilla resistance. In areas of the Philippines where resistance was strong, Japanese troops tended to regard any civilian as a “possible guerilla collaborator,” and therefore felt justified in doing anything to “women belonging to the enemy.” Indeed seven out of the above-mentioned 51 victims testified that they were abducted by the Japanese during guerilla mopping-up operations.

In almost all of the 51 testimonies that have so far been collected in the Philippines, the victims were abducted by Japanese soldiers from home, work, or while walking in the street. In some cases, abductions were planned, but in many cases the women were simply picked up on the road by a small group of Japanese soldiers and taken to a Japanese garrison nearby, where they were raped day after day. The duration of captivity was usually between one and several months. In a few cases victims were confined for up to two years. In most cases the premises where they were confined were part of the garrison compound or right next to it. They were guarded by Japanese soldiers 24 hours a day, providing very little chance of escape. This was quite different from the typical comfort station in other parts of Asia, which in most cases was a facility completely separate from the barracks, and managed by a Japanese or Korean civilian proprietor under the supervision of the military authorities.

In the Philippines it seems that the usual practice was that about 10 young women or girls were held by each small, company-size army unit for the exclusive exploitation of the unit. Most commonly a victim would be raped by five to ten soldiers every day. None of the victims were ever paid and some were forced to cook and wash for the Japanese soldiers during the day and then provide sexual services at night. It is believed that, as in comfort stations in “hostile districts” in China, stations where these Filipina girls were confined were also set up without official approval by the regional headquarters.

Another distinctive feature of comfort women both in the Philippines and China is that they became victims of military sexual violence at very young ages.

The average age of the Filippina comfort women for which we have information was 17.6 years. Many were younger than 15 years old and one was as young as 10 years old. Naturally, the younger girls had not yet begun to menstruate. The explanation why the Japanese victimized such young girls may require further investigation in the future.

Continuous rape in captivity was undoubtedly a tormenting experience for

them, but tragically some of these Filipina girls had had to endure the additional horror of witnessing the murder of their own parents and siblings by the Japanese at the time of their abduction. For example, one night in 1942, two Japanese soldiers invaded the home of 13-year-old Tomasa Salinog and her father in Antique on Panay Island. As the two soldiers intruded, another two stayed outside on watch. Tomasa’s father resisted the soldiers as they tried to take the 50

Procurement of women and their lives

child away. One of the Japanese, Captain Hirooka, suddenly drew his sword and severed the man’s head in front of the girl’s eyes. She screamed loudly at the sight of her father’s head lying in the corner of the room, but the Japanese dragged her out of the house.53 In another case Rufina Fernandez, a 17-year-old Manila girl witnessed the murder of both her parents and one of her sisters when Japanese soldiers broke into their home one night in 1944. The Japanese tried to take her and her father away with them. When he resisted he was beheaded.

When her mother tried to do the same she was killed. Her youngest sister was also killed in front of her. Her two other younger sisters were crying as she was taken from the house. Their crying suddenly stopped, and she presumed that they, too, had been killed by the Japanese.54

The overall picture that can be drawn from these testimonies is strikingly similar to the situation experienced by many women in Bosnia-Herzegovina during the recent Bosnian War.55 The only notable difference is that the Japanese had no intention of deliberately making the girls pregnant as one method of “ethnic cleansing.” The words “comfort women” or “comfort station” are of course nothing but an official euphemism. As with the Bosnian case, “rape camps” is probably a more appropriate term to accurately describe the conditions of sexual enslavement into which many Filipinas and Chinese girls were pressed.

Life as a comfort woman

The experiences of comfort women at officially approved comfort stations were as inhumane as, if not worse than, those of the Filipina and Chinese girls that we have cited.

When the girls were informed about the real nature of the work, it was quite natural for them to refuse to work as comfort women. Some demanded that the comfort station manager send them back home as the job they had been promised was found to be false. Typically the manager would inform them that the large advance payment made to their parents had to be paid back before they would be sent back home. Even where no advance payment had been made, the manager would demand repayment of the cost of transporting them from their home to the locality of the comfort station, the cost of daily meals and clothes, plus interest on those costs. When they realized that they were trapped by this sort of “indentured system,” it was too late to reverse the situation.

Yet some women still tried to refuse being made sexual slaves. Their resistance was met by force, often by torture, in order to get their consent, and some were maimed or killed. Yi Yongsu was one such woman who experienced extreme brutality as the result of initial refusal. The following is an excerpt from her testimony:

The man who had accompanied us from Taegu turned out to be the proprietor of the comfort station we were taken to. We called him Oyaji [i.e. boss or master]. I was the youngest among us. Punsun was a year older than me

Procurement of women and their lives

51