John Aubrey: My Own Life (32 page)

Read John Aubrey: My Own Life Online

Authors: Ruth Scurr

. . .

All Saints’ Church

16

, Kingston-upon-Thames, is spacious and the steeple is leaded, wherein eight bells hang. Three of the Saxon kings were crowned here: Athelstan, Edwin and Eldred. The windows of the church are of several fashions, which is as much as to say they are of several ages, but most are of the time of King Richard II.

. . .

West of Kingston-upon-Thames, near Thames-side, is a spring that is cold in summer and warm in winter. It bubbles and is called Seething Well. The inhabitants wash their eyes in its water and drink it for health.

. . .

At Cobham

17

there is a medicinal well that was discovered a few years ago by a countryman using the water in his food and giving it to his pigs. I am told that at the bottom of this well are stones like Bristol Diamonds.

. . .

At Norbury

18

near Letherhed, Sir Richard Stidulph has 40,000 walnut trees. It is likely that there are more walnut trees in this county than there are in all England besides.

. . .

At Deepdene

19

, Sir Charles Howard of Norfolk has contrived a long valley in the most pleasant and delightful solitude for house, gardens, orchards and boscages that I have seen in England. From the top of the hill and vineyard there is a prospect over Sussex, towards Kent, and so to the sea.

I have spent today drawing a careful plan of Deepdene, but it deserves a poem! This place is a subject worthy of Mr Abraham Cowley’s Muse.

Sir Charles has shaped his valley in the form of a theatre with more than six narrow walks on the sides, like rows of seats, one above the other. They were made with a plough and are bordered by thyme (there are twenty-one varieties in this garden), cherry trees and myrtles. There are many orange trees and syringas too, which are in flower at this time of year. The pit (or bottom of the valley) is full of rare flowers and choice plants.

The gardens are tended by two pretty lads who wonderfully delight in their occupation and the lovely solitude. It is as though they are outside this troublesome world and live in the state of innocency.

There is a cave on the left-hand side of the hill, thirty-six paces long, four broad and five yards high, and two thirds of the way up the hill there is another subterranean walk through which there is a vista over all of southern Surrey towards the sea.

There is a vineyard

20

of about eight acres on the south side of the hill. On the west side there is a little building, which Sir Charles uses as a laboratory and oratory.

The house was not made for grandeur, but for retirement. It is a noble hermitage: neat, elegant and suitable to the modesty and solitude of its proprietor, who is a Christian philosopher, who lives up to those of primitive times.

On the orders of Sir Charles, his steward, Mr Newman, gave me a very civil entertainment. The pleasure of the garden, etc. was so ravishing that I can never expect enjoyment beyond it, except in the Kingdom of Heaven. It is an epitome of paradise; an imitation of the Garden of Eden.

. . .

I have copied

21

a draft of the River Mole from Sir Charles Howard’s map of the Manor of Dorking.

. . .

As I rode

22

over Albury Down, I was wonderfully surprised by the prodigious snails there, which are two or three times as big as our common snails.

. . .

On Letherhed Down

23

there is a perfect Roman way in the road from London to Dorking. I asked the shepherds if there are any traces of it on Bansted Downs, but they know not. The shepherds here use a half horn nailed to the end of a long staff, with which they can throw a stone a good way to keep their sheep within their bounds or from going into the corn. I have seen pictures of such staffs in some old hangings and at the front of the first edition of Sir Philip Sidney’s

Arcadia

, but never saw the thing itself but on these downs.

. . .

In Albury Park

24

there is a spring called Shirburn Spring which breaks out at the side of the hill, over which is built a handsome banqueting house, surrounded by trees, which yield a pleasant solemn shade. Below the house is a pond that entertains you with the reflection of the trees above. Albury was purchased by Sir Thomas Howard, Lord Marshall in 1638.

. . .

Today I went to find the place of the great mathematician Mr William Oughtred’s burial in the chancel at Albury, on the north side near the cancelli. I had much ado to find the very place where the bones of this learned and good man lay. When I first asked his son Ben, who lodges with my cousin, where to look, he said his grief for his father was so great that he could not remember. But after he put on his considering cap (which is nothing like his father’s), he did remember.

In the chancel there is no memorial to Mr Oughtred, which grieves me, so I will ask Mr John Evelyn to speak to our patron the Duke of Norfolk about bestowing a decent marble inscription to perpetuate his fame. He did honour to the English nation as a mathematician and was rector of this parish for many years. During his lifetime he was more famous abroad than at home; foreign mathematicians would travel to England to consult him. He died on 13 June 1660, aged eighty-eight. His great friend Ralph Greatrex said he died for joy at the coming-in of the King. ‘And are you sure he is restored?’ Mr Oughtred asked. ‘Then give me a glass of sack to drink his sacred majesty’s health.’ Afterwards his spirits were on the wing to fly away.

I have questioned Ben closely about his father and whether he died a Roman Catholic. Ben insists not. It is true that when Mr Oughtred was sick, some came to tamper with him, but he was past understanding. Ben was by his bedside.

Ben remembers

25

how his father talked much of the philosopher’s stone. He remembers him using quicksilver, refined and strained, and gold, to try and make the stone. Mr Oughtred was an astrologer who foretold luckily. His wit was always working – I say the same of myself – and he would draw lines and diagrams in the dust.

. . .

I went to see the remains

26

at Blackheath, where there is a toft (as the lawyers term it) of a Roman temple on a plain a stone’s throw eastwards from the road to Cranley. Some of the Roman tiles here are of a pretty kind of moulding with eight angles and there are some lumps of stone with Roman mortar. Ben Oughtred says that forty years ago one might have seen the remains plainly which were as high as the top of the banks are now. I deduced from a piece of extant ground pinning that it was square, since it goes straight at an angle. But two years ago the wall was dug up for stone and brick, and now the remains are so mangled that I cannot tell what to make of them. I found some pieces of Roman tiles and brick on the heath, where there was a great deal of building in old times. The tradition of the old people hereabouts is that there was once a river that ran below the temple. And that is all I could discover. What a pity a drawing of the temple was not taken some hundred years ago. Posterity would have been grateful! But there were many more Roman temples in Britain of which no vestiges at all remain.

. . .

I have reached Guilford

27

. Here is a stately almshouse built of brick with a quadrangle and a noble tower with a turret over the gate. There is a fair dining room at the upper end where there is a picture of the founder, George Abbot, Archbishop of Canterbury. Here is also a picture of Sir Nicholas Kempe, the knight who gave a hundred pounds in his lifetime at the laying of the first stone and at his death five hundred more to this hospital: a worthy benefactor.

. . .

In Our Lady’s Chapel at Trinity Church in Guilford is a sumptuous monument of marble of Archbishop George Abbot. He was the son of a Sherman. When his mother was pregnant with him, she longed for pike, and dreamed that if she could eat pike her son would be a great man. The next morning, going down to the river to collect some water, she caught a pike in her pail and ate it.

. . .

Mayden-hair grows

28

plentifully about Lothesley Manor (the seat of Sir William Moore) and about the heath nearby grows plentiful wild sage, St John’s Wort, whorehound and a great store of Chamaepitys or ground-pine, which the apothecaries make much use of: they send for it from beyond the sea.

. . .

Here at Frensham

29

is an extraordinary great pond, made famous by the London fishmongers for the best carp in England. It contains 114 acres and is accounted three miles about.

. . .

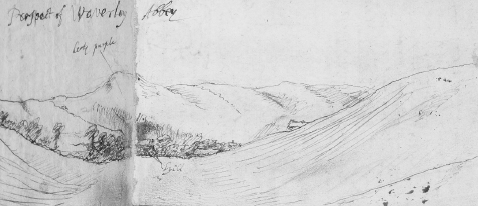

Waverley Abbey is situated

30

low, but in very good air, and is as romantic a place as most I have seen. Within the walls are sixty acres. The walls are very strong, chiefly of ragstone, ten foot high. There are also remains of a fair church and cloister, and handsome chapel, which is now a stable, larger than that at Trinity College, Oxford. The windows are of the same fashion as the chapel windows at St Mary’s Priory in Wiltshire.

. . .

Waverley was the mother church

31

to the church at Farnham. The vicarage is a living of 80 li. per annum, in the gift of the Bishop of Winchester. My old tutor at Trinity College, Mr William Browne, became vicar of Farnham and lies buried here around the middle of the chancel, but without any memorial. I paid my respects to him today. He died of smallpox on 21 October 1669, after he had been vicar here for about eight years, appointed by Bishop Morley. He was born at Churchill in Dorset and his father was rector there. Like me he was educated at Blandford, then went on to Trinity College. He was an ingenious person, a good scholar and as admirable a disputant as any in the University at that time. It was my happiness to have been his pupil. He wrote often to me from Oxford after my father summoned me home during the civil wars.

. . .

Above the town

32

of Farnham there is a stately castle, belonging to the Bishop of Winchester. At the beginning of the civil wars, in 1642, Sir John Denham of Egham was High Sheriff of this county. He secured the castle for the King for some time, but being so near to London, he could not hold it. It became a garrison for Parliament and was much damaged. After the wars, Bishop Morley repaired it, but without the advice of an architect, as may be seen from the way the windows are not placed exactly over one another. Not only does this weaken the building, it also offends the eye.

. . .

In Woking I spoke

33

with a gravedigger today whose father gave him a rule whereby you may avoid digging a grave in ground where a corpse has already rotted. There is a certain plant – about the size of the middle of a tobacco pipe – which grows near the surface of the earth, but never appears above it. It is very tough and about a yard long, the rind of it is almost black and tender so that when you pluck it, it slips off, and underneath is red. It has a small button on the top, resembling the top of an asparagus. The gravedigger says he always finds two or three of these plants in a grave, and has promised to send me some. He is sure it is not a fern root, and finds that it springs from the putrefaction of the dead body. In this fine soil, graves quickly disappear: the wind and the scuffing of boys playing above them soon merge them back into the ground. So it is often not easy for the gravedigger to tell where graves have been before, but when he comes across the plant that feeds on putrefying flesh, he knows to dig no further. He tells me this holds true only for his own churchyard, and the one at Seend a mile or two away. Of others he would say nothing. The plant he described reminded me of µολη (moly), mentioned by Homer, except that Homer says it puts forth a little white flower just above the earth’s surface.

. . .

The cheese of this county

34

is very bad and poor. They rob their cheese by taking out the butter, which they sell to London. They are miserably ignorant as to making dairy produce, except butter. A gentlewoman of Cheshire moved into these parts (near Albury) and misliking the cheese here sent for a dairymaid out of her own county. But when the dairymaid came she could not, with all her Cheshire, make any good cheese here.

. . .

Croydon market

35

is considerable for oats.

. . .

Bordering on Hampshire

36

, Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Middlesex lies the Hundred of Godley or Chertsey, which takes its name from the town Chertsey, lying on the banks of the River Thames.