John Brown (27 page)

This done, Dr Reid requested everyone to withdraw except Mrs Tuck, and the two junior dressers Miss Stewart and Miss Ticking. Certain that the door to the chamber was firmly closed, Dr Reid proceeded with the most secret of his funeral duties. Once the Queen’s wedding veil had been spread over her face and upper body, now dressed in a white silk robe and the Order of the Garter, he placed in her left hand a photograph of John Brown. In a sheet of tissue paper he folded a lock of Brown’s hair set in a case and hid it under a corsage of flowers which the new Queen Alexandra had laid on the body after its placement in the shell. Herein, too, Reid positioned a pocket handkerchief that had belonged to Brown, and a ring that had been John Brown’s mother’s and which the Queen had worn constantly for the eighteen years since Brown’s death. To these Reid added a few other photographs and letters that had passed between them.

4

Despite further last viewings of the dead Queen by family and court members all the John Brown items remained undisturbed and unseen, until at last the outer coffin lid was finally screwed in place.

Queen Victoria’s coffin now lay in state for a while in the dining room at Osborne House, watched over by four Grenadier Guards, their rifles ceremonially reversed. On 1 February her funeral cortège processed through East Cowes to the anchorage of the royal yacht

Alberta

, which took the mourning party across the Solent for the journey by train to London. On Monday 4 February the final ceremony of Queen Victoria’s funeral took place with interment of her body at Frogmore mausoleum alongside Prince Albert. When the royal family had filed past the royal coffin and all the ecclesiastical and Court officials had left, Reginald Baliol Bret, 2nd Viscount Esher, Secretary of the Office of Works, who had stage-managed the day’s events, watched the workmen lower the coping-stone over the royal vault. Thus were the Queen’s last secrets sealed away. Yet just a few yards away from the royal tomb, now topped with effigies of Prince Albert and Queen Victoria, in the ambulatory of the Chapel of the Crucifixion, lies a clue to their presence. Here Queen Victoria had arranged for a bronze tablet to be affixed, ‘In loving and grateful remembrance’ of Brown her ‘faithful and devoted personal attendant and friend’.

5

The tablet was the sole non-family memorial that the Queen ever allowed in the hallowed shrine she had set up for herself and her beloved husband.

6

From time to time stories of ‘compromising letters’, which are said to have passed between Queen Victoria and John Brown, are given the oxygen of publicity. Following the première in 1998 of the film

Mrs Brown

, starring Dame Judi Dench as Queen Victoria and Billy Connolly as John Brown, the British press ran a story under the general heading ‘Mrs Brown’s love letters revealed: Film-makers discover hoard of mementoes from Queen Victoria to gillie John Brown.’

7

The article said that a ‘secret cache’ of compromising letters had been located in the attic of a house ‘near Ballater’. These had been read by the film’s executive producer Douglas Rae and writer Jeremy Brocks, who ‘were allowed to use the content of the letters to provide most of the background of the film’. The whereabouts and provenance of the letters is shrouded in mystery and the purported ‘owners’ are reported to have said that the letters ‘will not be made public until the next century’. The fatuous reason given is that the ‘owners’ ‘don’t want anything revealed while the present members of the Royal Family, particularly the Queen Mother, are still alive’.

8

The definition of ‘compromising’ with regard to correspondence between Queen Victoria and John Brown is open to debate and should be assessed from the point of view of Queen Victoria’s character and personality rather than in prurient twentieth-century terms. Anything relating to the friends, especially the Queen’s gushing words of familiarity and amity – which is probably the best explanation of the Queen’s use of ‘love’ and ‘darling one’ to John Brown – would be considered ‘compromising’ by the paranoid Edward VII who himself was drawn into one episode concerning such letters.

In late September 1904 Dr James Reid was contacted by Edward VII’s private secretary, Francis Knollys, who said that the monarch wished to consult Reid on a private matter. The late Dr Alexander Profeit’s son George was in the process of threatening the King with blackmail concerning letters written by Queen Victoria to Dr Profeit about John Brown. George Profeit had opened a black trunk of his father’s and discovered in excess of three hundred letters, ‘many of them most compromising’ noted Dr Reid.

9

The King wanted Reid to obtain the letters from George Profeit.

Dr Reid was perplexed about how to proceed. During November 1904 he asked for a meeting with Princess Beatrice at Kensington Palace to talk over the problem. The King was willing to pay for the letters; the important point was that the monarch

must

have them. Shortly after the interview with Princess Beatrice, George Profeit met Reid to negotiate the sale. It took several visits from the difficult vendor to complete the negotiations, but on 8 May 1905 George Profeit handed over the letters for an undisclosed sum. Reid personally gave them to the King.

10

The ‘compromising’ letters thereafter disappeared, adding one more twist to the mystery surrounding the relationship between Queen Victoria and John Brown, the fine detail of which is unlikely ever to be known for certain.

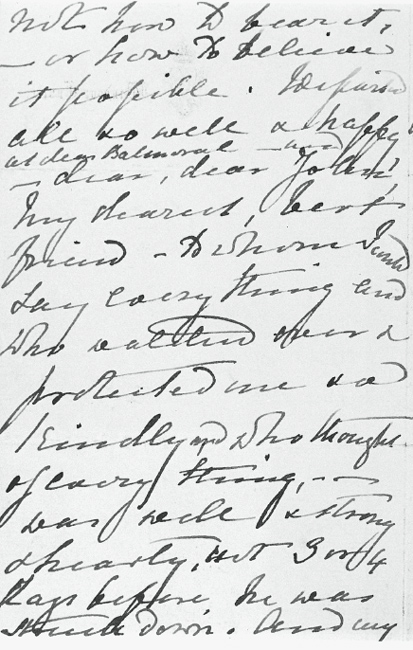

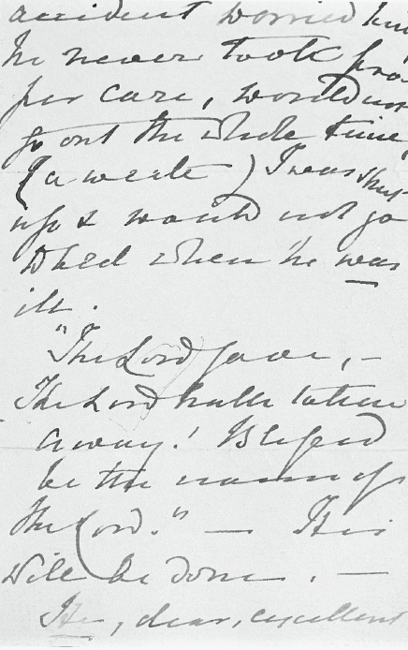

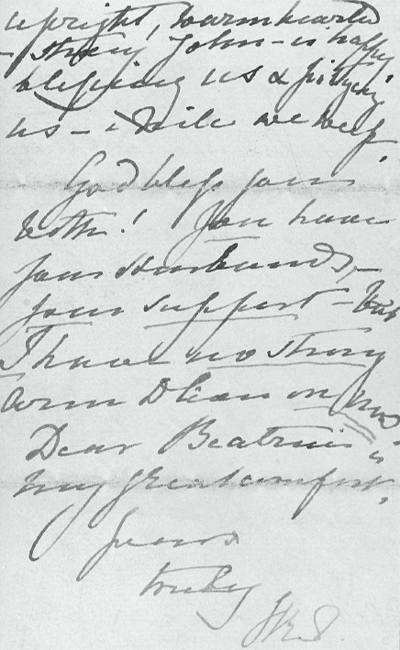

Holograph letter from Queen Victoria, expressing her grief at the death of John Brown, addressed to his sisters-in-law ‘Lizzie’ (Mrs William Brown) and ‘Jessie’ (Mrs Hugh Brown). [See p. 142]

Q

UEEN

V

ICTORIA

’

S

C

HILDREN AND

T

HEIR

A

NTIPATHY TO

J

OHN

B

ROWN

1.

VICTORIA ADELAIDE MARY LOUISA

, Princess Royal. Born 21 November 1840. Married: 1858, Prince Frederick William of Prussia (1831–88). Became Crown Princess of Prussia and Empress Frederick of Germany. She had eight children including the autocratic and mentally unstable Wilhelm II (1859–1941), ‘Kaiser Bill’ of the First World War. She died 5 August 1901.

Princess Victoria was embarrassed and resentful over gossip at the German court regarding Queen Victoria and John Brown. She sent the queen a ‘rather formal message’ of sympathy on John Brown’s death.

2.

ALBERT EDWARD

, Prince of Wales.

Born 9 November 1841. Married: 1863, Princess Alexandra of Denmark (1844–1925). They had five children. Died 6 May 1910, having acceded to the throne on the death of Queen Victoria as Edward VII.

Harboured a lifelong hatred of John Brown, substituting the phrase ‘that brute’ for his name in conversation.

3.

ALICE MAUD MARY

.

Born 25 April 1843. Married: 1862, Prince Louis IV, Grand-Duke of Hesse-Darmstadt (1837–92). She had seven children. Died 14 December 1878.

Supported her elder brother and sister in trying (unsuccessfully) to get John Brown sacked.

4.

ALFRED ERNEST ALBERT

, Duke of Edinburgh and Saxe-Coburg-Gotha.

Born 6 August 1844. Married: 1874, Grand Duchess Marie of Russia (1853–1920). They had five children. Died 30 July 1900.

Resented John Brown’s ‘power and confidence’ at court, and was the centre of many ‘Brown rows’ with Queen Victoria.

5.

HELENA AUGUSTA VICTORIA

.

Born 25 May 1846. Married: 1866, Prince Frederick Christian of Schleswig-Holstein (1831–1917). She had five children. Died 9 June 1923.

Admitted to being ‘wholeheartedly’ German and was irritated by ‘John Brown gossip’ in Prussian imperial circles.

6.

LOUISE CAROLINE ALBERTA

.

Born 18 March 1848. Married: 1871, John Douglas Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll (1845–1914). No issue. Died 3 December 1939.

Looked upon John Brown as a ‘mischief-maker’ and believed that he ‘tittle-tattled’ about her private life to Queen Victoria. Gave her an aversion to Highland gillies.

7.

ARTHUR WILLIAM PATRICK ALBERT

, Duke of Connaught and Strathearn.

Born 1 May 1850. Married: 1879, Princess Louise Margaret of Prussia (1860–1917). They had one son and two daughters. Died 16 January 1942.

Shared his siblings’ distaste for John Brown’s ‘interference’.

8.

LEOPOLD GEORGE DUNCAN ALBERT

, Duke of Albany.

Born 7 April 1853. Married: 1882, Princess Helena Frederica Augusta of Waldeck and Pyrmont (1861–1922). They had two children. Died 28 March 1884.

As a child he seems to have been on fairly friendly terms with John Brown, who took him and his brother Arthur fishing. Hatred of Brown (and his brothers) was demonstrated in the ‘Stirling Dismissal’ episode.

9.

BEATRICE MARY VICTORIA FEODORE

.

Born 14 April 1857. Married: 1885, Prince Henry Maurice of Battenberg (1858–96). She had four children. Died 26 October 1944.

To her John Brown was ‘the ever present faithful servant’ and when he was around ‘one was safe’. Princess Beatrice and Prince Arthur were the executors to Queen Victoria’s will, and as her mother’s literary executor Princess Beatrice ‘edited’ her personal papers and vast collection of correspondence, deleting and destroying any mention of John Brown that might be construed as ‘compromising’ and open to misinterpretation.

P

ROLOGUE

: B

IRTH OF

R

OYAL

R

UMOUR

1. Philip Magnus-Allcroft,

King Edward VII

, p. 359.

2. E.E.P. Tisdall,

Queen Victoria’s John Brown

, pp. 232–3.

3. Catalogue:

British and Continental Paintings and Watercolours

, Christie’s Scotland, 28 May 1998, p. 92. The canvas, signed by Carl Rudolph Sohn (1854–1908) was catalogued as picture 2066 (1884). It was duly sent to William Brown and was stored in a byre for forty-three years; it was sold in 1944 and 1963 and in 1965 was acquired by the Scottish Tartan Society who sold it on in 1998.