John Quincy Adams (21 page)

Authors: Harlow Unger

On July 11, 1804, while John Quincy was still in Massachusetts copying Donne's erotic verses for Louisa, Senate president Aaron Burr Jr., the vice president, shot and killed former Treasury secretary Alexander Hamilton in a duel. Fifteen years in the making, their enmity had reached a climax earlier in the year during the New York gubernatorial election campaign, when Burr called for “a union at the northward” between New York and the New England states to thwart the assumption of power by Jefferson, Madison, and Virginia's political dynasty. Fearing civil war, Hamilton all but ensured Burr's defeat in the gubernatorial election by calling the vice president “a dangerous man who ought not to be trusted with the reins of government.”

27

Jefferson had already rejected Burr as a potential running mate in 1804, and Burr's defeat in the gubernatorial race effectively ended his political career. As Hamilton's barbs struck, the editor of the

American Citizen

added to their sting by calling Burr the “most mean and despicable bastard in the universe . . . so degraded as to permit even General Hamilton to slander him with impunity.”

28

Burr sued the editor, then challenged Hamilton to the fatal confrontation.

27

Jefferson had already rejected Burr as a potential running mate in 1804, and Burr's defeat in the gubernatorial race effectively ended his political career. As Hamilton's barbs struck, the editor of the

American Citizen

added to their sting by calling Burr the “most mean and despicable bastard in the universe . . . so degraded as to permit even General Hamilton to slander him with impunity.”

28

Burr sued the editor, then challenged Hamilton to the fatal confrontation.

After the duel, outraged Hamilton supporters posted handbills bearing the words “Hang Burr!” on walls across New York City. A grand jury indicted Burr for murder, but he fled to a hideaway on a Georgia plantation. When the Senate reconvened on November 5, however, John Quincy joined other members in a collective gasp as Burr stepped through the door and strode down the aisle to his accustomed chair as president of the Senate.

“The coroner's inquest,” John Quincy wrote in disbelief, “found a verdict of willful murder by Aaron Burr, vice president of the United States. The grand jury . . . found a bill against him for murder. Under all these circumstances Mr. Burr appears and takes his seat as president of the Senate of the United States.”

29

29

John Quincy grew even more annoyed when the Senate voted to go into executive sessionâand promptly left the Capitol to go to the horse

races. And they repeated the exercise for the next ten days. “The consideration of executive business,” John Quincy fumed, was “merely for the sake of having on the

printed

journals an

appearance

of doing business though there was really none to do. This vote passed. . . . Mine was the only voice heard against it.”

30

races. And they repeated the exercise for the next ten days. “The consideration of executive business,” John Quincy fumed, was “merely for the sake of having on the

printed

journals an

appearance

of doing business though there was really none to do. This vote passed. . . . Mine was the only voice heard against it.”

30

Earlier in the year, an effort by President Jefferson to alter the Federalist bias of the Supreme Court came to fruition when he coaxed his political allies in the House of Representatives to impeach Associate Justice Samuel Chase. A signer of the Declaration of Independence and appointee of President Washington, Chase had, at times, displayed outrageous political bias in his rulings, but he crossed a particularly dangerous political line by attacking the adoption of universal white manhood suffrage in his native state of Maryland. Until then, only property owners had been able to vote. Chase argued that the “constitution will sink into a mobocracy, the worst of all possible government,” and he cited as “a mighty mischief ” the doctrine “that all men in a state of society are entitled to enjoy equal liberty and equal rights.”

31

31

Calling his words an improper political address in a judicial proceeding, the House of Representatives charged him with sedition and treasonâboth of them “high crimes and misdemeanors” and a basis for impeachment under the Constitution and removal from office. With John Quincy howling his objections, Chase went on trial before the Senate the following February. In one of the most important trials in American history, the House of Representatives threatened to convert the American republic into an autocracy by criminalizing political dissent. Although John Quincy did not like Chase, he argued that the constitutional phrase “high crimes and misdemeanors” referred to indictable criminal actsânot political statementsâand he convinced the Senate to support him. On March 1, 1805, after the Senate had voted, Vice President Burr announced, “There not being a constitutional majority who answer âguilty' to any one charge, it becomes my duty to declare that Samuel Chase is acquitted upon all the articles of impeachment brought against him by the House of Representatives.”

32

In what was then the most significant defense of the First Amendment ever

mounted, John Quincy had prevented the American President and the House of Representatives from criminalizing free speech.

32

In what was then the most significant defense of the First Amendment ever

mounted, John Quincy had prevented the American President and the House of Representatives from criminalizing free speech.

“This was a party prosecution,” John Quincy reflected afterwards, “and has issued in the . . . total disappointment of those by whom it was brought forward.”

It has exhibited the Senate of the United States fulfilling the most important purpose of its institution, by putting a check upon the impetuous violence of the House of Representatives. It has proved that a sense of justice is yet strong enough to overpower the furies of faction. . . . The attack on Mr. Chase was a systematic attempt upon the independence and powers of the Judicial Department and, at the same time, an attempt to prostrate the authority of the National Government before those of the individual states.

33

33

Just before the Chase trial, the Electoral College had announced the results of the presidential elections, with Thomas Jefferson the overwhelming victor over South Carolina Federalist Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, winning 162â14. With Aaron Burr out of the picture, former New York governor George Clinton, an ardent Republican, easily won the vice presidency. Republicans gained control of both houses of Congress. With their own seats secure until 1809, John Quincy and one-third of his colleagues had not faced reelection, but he now stood alone in the Senate, shunned by Federalists and Republicans alike because he invariably put preservation of the union and the nation's independence from foreign influence ahead of party interests.

The day after the Chase trial, Vice President Burr announced his retirement from the Senate, and with his resignation, the Eighth Congress adjourned. The following day saw the President return to the Capitol for his second inauguration, and, perhaps chastened by his setback in the Chase case, he “delivered an inaugural address in so low a voice that,” according to John Quincy, “not half of it was heard by any part of the crowded auditory.”

34

34

After the inauguration, John Quincy's sons contracted chicken pox, but the Adamses nonetheless managed to go to Quincy for the summer,

where they took up residence in what now seemed the somewhat crude old farmhouse in which John Quincy had been born.

where they took up residence in what now seemed the somewhat crude old farmhouse in which John Quincy had been born.

It stood at a distance from, but on the same land as, the newer, more luxurious retirement “mansion” where John and Abigail had installed themselves and where John Quincy spent evenings discussing politics with his father. After renovating the old house into a comfortable summer retreat, John Quincy took up gardening as a new hobby that allowed him to spend more time in the fresh air.

Early in June, Harvard named John Quincy professor of oratory and rhetoric, a chair created by a bequest in 1771 from Nicholas Boylston, a first cousin of John Quincy's grandmother. John Quincy worked out terms that would allow him to lecture when the Senate was out of session, with payment of $348 per quarter. Although he would not begin until the following year, in June 1806, he snapped up copies of Cicero's

Orations

, Thomas Leland's

Demosthenes

, and works by Aristotle to prepare his first lectures.

Orations

, Thomas Leland's

Demosthenes

, and works by Aristotle to prepare his first lectures.

During the next session of Congress, John Quincy dined frequently at the President's House with Jefferson and Secretary of State Madison, and after an uneventful winter session, he returned to Massachusetts to prepare his Harvard lectures and open his Boston law office. Too far along with another pregnancy, Louisa again remained with her family in Washington and, in early July, lost another child. John Quincy wrote to her, repeating his thanks to God “for having preserved you to me through the dangers of that heavy trial both of body and mind which it has called you to endure.”

35

35

In 1806, the endless Anglo-French conflict spilled into the Atlantic again. The British reversed course and seized American ships, confiscated cargoes, and impressed hundreds of seamen. Early in 1807, John Quincy proposedâand the Senate passedâthree resolutions, two of which assailed British actions as “unprovoked aggression” and “a violation of neutral rights.” The third resolution authorized the President to embargo all U.S. exports. Jefferson, Madison, and John Quincy believed that ending the flow of essential American goods to both England and France would force

those countries to end their war with each other and their depredations on American ships. The embargo would not prevent imports from entering American ports, but ships carrying such goods would have to leave port empty, and few shipowners could afford such one-way trade. John Quincy was the only Federalist in either house of Congress to vote for the embargo, which he believed was a middle ground between a suicidal naval war with Britain and passive acquiescence to British rule over international sea-lanes.

those countries to end their war with each other and their depredations on American ships. The embargo would not prevent imports from entering American ports, but ships carrying such goods would have to leave port empty, and few shipowners could afford such one-way trade. John Quincy was the only Federalist in either house of Congress to vote for the embargo, which he believed was a middle ground between a suicidal naval war with Britain and passive acquiescence to British rule over international sea-lanes.

Â

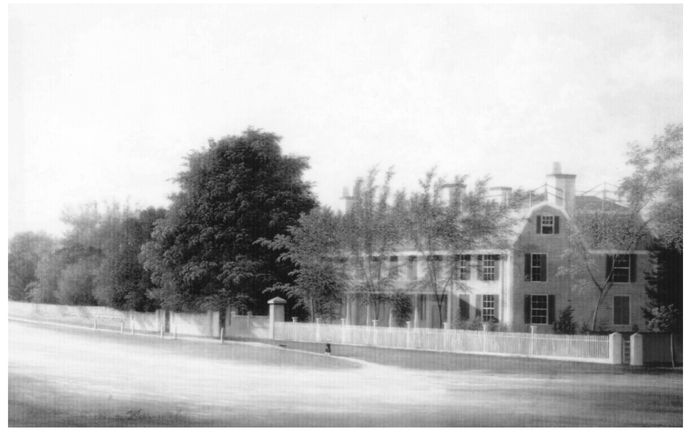

John Adams built this lavish “mansion” as a retirement home for himself and his wife, Abigail. See illustration no. 2, page 10, to view the entire Adams family farm.

(PAINTING BY G. FRANKENSTEIN, 1849; NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

(PAINTING BY G. FRANKENSTEIN, 1849; NATIONAL PARKS SERVICE, ADAMS NATIONAL HISTORICAL PARK)

Political isolation in Congress only intensified his loneliness. After the Christmas holidays, Louisa had remained in Boston with John II to be near George's boarding school and see him on Sundays. Though surrounded by in-laws, John Quincy longed for his wife and children. At the end of a particularly cold winter day in Washington, he wrote to Louisa before going to bed, “I will not say I can neither live with you nor without you; but in this cold weather I should be very glad to live with you.”

36

36

Increasingly obsessed by thoughts of his wife, he spent his lonely evenings writing poems, dedicating

A Winter's Day

“To Louisa”:

A Winter's Day

“To Louisa”:

In another poem, he pleaded with Louisa to

She replied playfully, calling his words “the sauciest lines I ever perused” and asking whether he would like her to publish them.

39

39

When Congress adjourned in the spring of 1807, John Quincy returned to Massachusetts to find Louisa pregnant again, and in mid-August, she gave birth to their third son, Charles Francis Adams, whom John Quincy named for his dead brother Charles and for Francis Dana, the diplomat John Quincy had served as an adolescent in Russia.

As Boston Federalists demanded reconciliation with Britain, the British stepped up their outrages against American vessels on the high seas, with the worst occurring on June 22, 1807, when the British frigate

Leopard

hailed the USS

Chesapeake

just outside the three-mile territorial limit off Virginia's Norfolk Roads. As the American ship slowed, the British commander demanded permission to search the

Chesapeake

for four men he claimed were British deserters. When the American commander refused, the

Leopard

fired without warning, killing three Americans and wounding eighteen. The British boarded and, stepping over the dead and wounded on the deck, seized four men they claimed were British deserters. They hung one of the men from the yardarm and impressed the three others. The attack convinced President Jefferson and John Quincy that, short of war, the only effective way to prevent British attacks was to withdraw American ships from the oceans, impose the congressionally sanctioned embargo, and try to undermine the British economy.

Leopard

hailed the USS

Chesapeake

just outside the three-mile territorial limit off Virginia's Norfolk Roads. As the American ship slowed, the British commander demanded permission to search the

Chesapeake

for four men he claimed were British deserters. When the American commander refused, the

Leopard

fired without warning, killing three Americans and wounding eighteen. The British boarded and, stepping over the dead and wounded on the deck, seized four men they claimed were British deserters. They hung one of the men from the yardarm and impressed the three others. The attack convinced President Jefferson and John Quincy that, short of war, the only effective way to prevent British attacks was to withdraw American ships from the oceans, impose the congressionally sanctioned embargo, and try to undermine the British economy.

When Britain refused to pay reparations for the

Leopard

attack, Congress converted John Quincy's resolution into the Non-Importation Act, which effectively ended all American foreign trade in December 1807. Although aimed at punishing Britain, the act punished Americans more. Within weeks, the embargo had shut New England's shipbuilding industry, its shipping trade, and its fishing fleet. With export outlets closed, farmersânorth and southâfound their produce a glut on the market. By spring, a wave of bankruptcies had shut businesses and farms across New England and New Yorkâquite the opposite of what Jefferson, Madison, and John Quincy had expected. All three believed the United States could survive as a self-sufficient economy, abandoning imports in favor of home manufactures and mitigating the effects of the embargo while the U.S. government built a larger navy and armed her cargo ships. The huge farm surpluses overwhelmed the internal economy, however, and plunged the nation into economic catastrophe.

Leopard

attack, Congress converted John Quincy's resolution into the Non-Importation Act, which effectively ended all American foreign trade in December 1807. Although aimed at punishing Britain, the act punished Americans more. Within weeks, the embargo had shut New England's shipbuilding industry, its shipping trade, and its fishing fleet. With export outlets closed, farmersânorth and southâfound their produce a glut on the market. By spring, a wave of bankruptcies had shut businesses and farms across New England and New Yorkâquite the opposite of what Jefferson, Madison, and John Quincy had expected. All three believed the United States could survive as a self-sufficient economy, abandoning imports in favor of home manufactures and mitigating the effects of the embargo while the U.S. government built a larger navy and armed her cargo ships. The huge farm surpluses overwhelmed the internal economy, however, and plunged the nation into economic catastrophe.

Other books

Florence and Giles by John Harding

Mary Ellen Courtney - Hannah Spring 02 - Spring Moon by Mary Ellen Courtney

The Door to Bitterness by Martin Limon

Heart of Clay by Shanna Hatfield

Valkyrie Rising (Warrior's Wings Book Two) by Currie, Evan

The Loves of Leopold Singer by L. K. Rigel

The Rainaldi Quartet by Paul Adam

A Dangerous Path by Erin Hunter

Rivers of Gold by Tracie Peterson