Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (120 page)

Read Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell Online

Authors: Susanna Clarke

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Literary, #Media Tie-In, #General

Lascelles half-turned his head, but he did not look at Child- ermass.

"May I see it?" asked Childermass.

"I left it at Bruton-street," said Lascelles.

Childermass looked a little surprized. "Very well then," he said. "Lucas can fetch it. We will hire a horse for him here. He will catch up with us again before we reach Hurtfew."

Lascelles smiled. "I said Bruton-street, did I not? But do you know? - I do not think it is there. I believe I left it at the inn, the one in Chatham where I waited for Drawlight. They will have thrown it away." He turned back to the fire.

Childermass scowled at him for a moment or two. Then he strode out of the room.

A manservant came to say that hot water, towels and other necessaries had been set out in two bed-chambers so that Mr Norrell and Lascelles might refresh themselves. "And it's a blind- man's holiday in the passage-way, gentlemen," he said cheerfully, "so I've lit you a candle each."

Mr Norrell took his candle and made his way along the passage- way (which was indeed very dark). Suddenly Childermass ap- peared and seized his arm. "What in the world were you thinking of?" he hissed. "To leave London without that letter?"

"But he says he remembers what it contains," pleaded Mr Norrell.

"Oh! And you believe him, do you?"

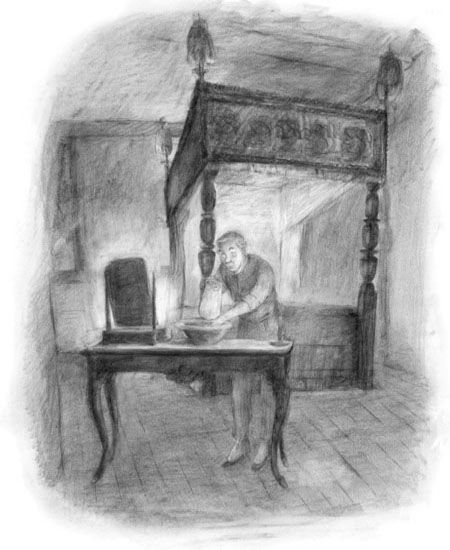

Mr Norrell made no reply. He went into the room that had been made ready. He washed his hands and face and, as he did so, he caught a glimpse in the mirror of the bed behind him. It was heavy, old fashioned and - as often happens at inns - much too large for the room. Four carved mahogany columns, a high dark canopy and bunches of black ostrich feathers at each corner all contrived to give it a funereal look. It was as if someone had brought him into the room and shewn him his own tomb. He began to have the strangest feeling - the same feeling he had had at the tollgate, watching the three women - the feeling that some- thing was coming to an end and that all his choices had now been made. He had taken a road in his youth, but the road did not lead where he had supposed; he was going home, but home had become something monstrous. In the half-dark, standing by the black bed, he remembered why he had always feared the darkness as a child: the darkness belonged to John Uskglass.

For always and for always

I pray remember me

Upon the moors, beneath the stars

With the King's wild company

He hurried from the room, back to the warmth and lights of the public parlour.

A little after six o'clock a grey dawn came up that was scarcely any dawn at all. White snow fell through a grey sky on to a grey and white world. Davey was so liberally coated in snow that one might have supposed that someone had ordered a wax-works model of him and the plaster mould was being prepared.

All that day a succession of post-horses laboured to bring the carriage through snow and wind. A succession of inns provided hot drinks and a brief respite from the weather. Davey and Child- ermass - who, as coachman and rider, were undoubtedly the most exhausted of the party - derived the least benefit from these halts; they were generally in the stables arguing with the innkeeper about the horses. At Grantham the innkeeper infuriated Child- ermass by proposing to rent them a stone-blind horse. Childermass swore he would not take it; the innkeeper on the other hand swore it was the best horse he had. There was very little choice and they ended by hiring it. Davey said afterwards that it was an excellent beast, hard-working and all the more obedient to his instructions since it had no other means of knowing where to go or what to do. Davey himself lasted as far as the Newcastle Arms at Tuxford and there they were obliged to leave him. He had driven more than a hundred and thirty miles and was, said Childermass, so tired he could barely speak. Childermass hired a postillion and they travelled on.

An hour or so before sunset the snow ceased and the skies cleared. Long blue-black shadows overlaid the bare fields. Five miles out of Doncaster they passed the inn that is called the Red House (by reason of its painted walls). In the low winter sun it blazed like a house of fire. The carriage went on a little way and then halted.

"Why are we stopping?" cried Mr Norrell from within.

Lucas leant down from the box and said something in reply, but the wind carried his voice away and Mr Norrell did not hear what it was.

Childermass had left the highway and was riding across a field. The field was filled with ravens. As he passed, they flew up with a great croaking and cawing. On the far side of the field was an ancient hedge with an opening and two tall holly-trees, one on each side. The opening led into another road or lane, bounded by hedges. Childermass halted there and looked first one way and then the other. He hesitated. Then he shook his reins and the horse trotted between the trees, into the lane and out of sight.

"He has gone into the fairy road!" cried Mr Norrell in alarm.

"Oh!" said Lascelles. "Is that what it is?"

"Yes, indeed!" said Mr Norrell. "That is one of the more famous ones. It is reputed to have joined Doncaster to Newcastle by way of two fairy citadels."

They waited.

After about twenty minutes Lucas climbed down from the box. "How long ought we to stay here, sir?" he asked.

Mr Norrell shook his head. "No Englishman has stept over the boundaries into Faerie since Martin Pale three hundred years ago. It is perfectly possible that he will never come out again. Perhaps . . ."

Just then Childermass reappeared and galloped back across the field.

"Well, it is true," he told Mr Norrell. "The paths to Faerie are open again."

"What did you see?" asked Mr Norrell.

"The road goes on a little way and then leads into a wood of thorn trees. At the entrance to the wood there is a statue of a woman with her hands outstretched. In one hand she holds a stone eye and in the other a stone heart. As for the wood itself . . ." Childermass made a gesture, perhaps expressive of his inability to describe what he had seen, or perhaps of his powerlessness in the face of it. "Corpses hang from every tree. Some might have died as recently as yesterday. Others are no more than age-old skeletons dressed in rusting armour. I came to a high tower built of rough- hewn stones. The walls were pierced with a few tiny windows. There was a light at one of them and the shadow of someone looking out. Beneath the tower was a clearing with a brook running through it. A young man was standing there. He looked pale and sickly, with dead eyes, and he wore a British uniform. He told me he was the Champion of the Castle of the Plucked Eye and Heart. He had sworn to protect the Lady of the Castle by challenging any one who approached with the intent of harming or insulting her. I asked him if he had killed all the men I had seen. He said he had killed some of them and hung them upon the thorns - as his predecessor had done before him. I asked him how the Lady intended to reward him for his service. He said he did not know. He had never seen her or spoken to her. She remained in the Castle of the Plucked Eye and Heart; he stayed between the brook and the thorn trees. He asked me if I intended to fight him. I reminded him that I had neither insulted nor harmed his lady. I told him I was a servant and bound to return to my master who was at that moment waiting for me. Then I turned my horse and rode back."

"What?" cried Lascelles. "A man offers to fight you and you run away. Have you no honour at all? No shame? A sickly face, dead eyes, an unknown person at the window!" He gave a snort of derision. "These are nothing but excuses for your cowardice!"

Childermass flinched as if he had been struck and seemed about to return a sharp answer, but he was interrupted by Mr Norrell. "Upon the contrary! Childermass did well to leave as soon as he could. There is always more magic in such a place than appears at first sight. Some fairies delight in combat and death. I do not know why. They are prepared to go to great lengths to secure such pleasures for themselves."

"Please, Mr Lascelles," said Childermass, "if the place has a strong appeal for you, then go! Do not stay upon our account."

Lascelles looked thoughtfully at the field and the gap in the hedge. But he did not move.

"You do not like the ravens perhaps?" said Childermass in a quietly mocking tone.

"No one likes them!" declared Mr Norrell. "Why are they here? What do they mean?"

Childermass shrugged. "Some people think that they are part of the Darkness that envelops Strange, and which, for some reason, he has made incarnate and sent back to England. Other people think that they portend the return of John Uskglass."

"John Uskglass. Of course," said Lascelles. "The first and last resort of vulgar minds. Whenever any thing happens, it must be because of John Uskglass! I think, Mr Norrell, it is time for another article in

The Friends

reviling that gentleman. What shall we say? That he was unChristian? UnEnglish? Demonic? Somewhere I believe I have a list of the Saints and Archbishops who denounced him. I could easily work that up."

Mr Norrell looked uncomfortable. He glanced nervously at the Tuxford postillion.

"If I were you, Mr Lascelles," said Childermass, softly, "I would speak more guardedly. You are in the north now. In John Uskglass's own country. Our towns and cities and abbeys were built by him. Our laws were made by him. He is in our minds and hearts and speech. Were it summer you would see a carpet of tiny flowers beneath every hedgerow, of a bluish-white colour. We call them John's Farthings. When the weather is contrary and we have warm weather in winter or it rains in summer the country people ay that John Uskglass is in love again and neglects his business.

1

And when we are sure of something we say it is as safe as a pebble in John Uskglass's pocket."

Lascelles laughed. "Far be it from me, Mr Childermass, to disparage your quaint country sayings. But surely it is one thing to pay lip-service to one's history and quite another to talk of bringing back a King who numbered Lucifer himself among his allies and overlords? No one wants that, do they? I mean apart from a few Johannites and madmen?"

"I am a North Englishman, Mr Lascelles," said Childermass. "Nothing would please me better than that my King should come home. It is what I have wished for all my life."

It was nearly midnight when they arrived at Hurtfew Abbey. There was no sign of Strange. Lascelles went to bed, but Mr Norrell walked about the house, examining the condition of certain spells that had long been in place.

Next morning at breakfast Lascelles said, "I have been wonder- ing if there were ever magical duels in the past? Struggles between two magicians? - that sort of thing."

Mr Norrell sighed. "It is difficult to know. Ralph Stokesey seems to have fought two or three magicians by magic - one a very powerful Scottish magician, the Magician of Athodel.

2

Catherine of Winchester was once driven to send a young magician to Granada by magic. He kept disturbing her with inconvenient proposals of marriage when she wanted to study and Granada was the furthest place she could think of at the time. Then there is the curious tale of the Cumbrian charcoal-burner . . ."

3

"And did such duels ever end in the death of one of the magicians?"

"What?" Mr Norrell stared at him, horror-struck. "No! That is to say, I do not know. I do not think so."

Lascelles smiled. "Yet the magic must exist surely? If you gave your mind to it, I dare say you could think of a half a dozen spells that would do the trick. It would be like a common duel with pistols or swords. There would be no question of a prosecution afterwards. Besides, the victor's friends and servants would be perfectly justified in helping him shroud the matter in all possible secrecy."

Mr Norrell was silent. Then he said, "It will not come to that." Lascelles laughed. "My dear Mr Norrell! What else can it possibly come to?"

Curiously, Lascelles had never been to Hurtfew Abbey before. Whenever, in days gone by, Drawlight had gone to stay there, Lascelles had always contrived to have a previous engagement. A sojourn at a country house in Yorkshire was Lascelles's idea of purgatory. At best he fancied Hurtfew must be like its owner - dusty, old-fashioned and given to long, dull silences; at worst he pictured a rain-lashed farmhouse upon a dark, dreary moor. He was surprized to find that it was none of these things. There was nothing of the Gothic about it. The house was modern, elegant and comfortable and the servants were far from the uncouth farmhands of his imagination. In fact they were the same servants who waited upon Mr Norrell in Hanover-square. They were London-trained and well acquainted with all Lascelles's prefer- ences.

But any magician's house has its oddities, and Hurtfew Abbey - at first sight so commodious and elegant - seemed to have been constructed upon a plan so extremely muddle-headed, that it was quite impossible to go from one side of the house to the other without getting lost. Later that morning Lascelles was informed by Lucas that he must on no account attempt to go to the library alone, but only in the company of Mr Norrell or Childermass. It was, said Lucas, the first rule of the house.