Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell (92 page)

Read Jonathan Strange and Mr Norrell Online

Authors: Susanna Clarke

Tags: #Fiction, #Fantasy, #Historical, #Literary, #Media Tie-In, #General

Childermass smiled. "Mr Norrell knows nothing about it. Shall I bring the money tonight?"

"Certainly. I shall not be at home, but give it to Jeremy. Tell me, Childermass, I am curious. Does Norrell know that you go about making yourself invisible and turning yourself into sha- dows?"

"Oh, I have picked up a little skill here and there. I have been twenty-six years in Mr Norrell's service. I would have to be a very dull fellow to have learnt nothing at all."

"Yes, of course. But that was not what I asked. Does Norrell

know

?"

"No, sir. He suspects, but he chuses not to

know

. A magician who passes his life in a room full of books must have someone to go about the world for him. There are limits to what you can find out in a silver dish of water. You know that."

"Hmm. Well, come on, man! See what you were sent to see!" The house had a much neglected, almost deserted air. Its windows and paint were very dirty and the shutters were all put up. Strange and Childermass waited upon the pavement while the footman knocked at the door. Strange had his umbrella and Childermass was entirely indifferent to the rain falling upon him.

Nothing happened for some time and then something made the footman look down into the area and he began a conversation with someone no one else could see. Whoever this person was, Strange's footman did not think much of them; his frown, his way of standing with both hands on his hips, the manner in which he admonished them, all betrayed the severest impatience.

After a while the door was opened by a very small, very dirty, very frightened servant-girl. Jonathan Strange, Childermass and the footman entered and, as they did so, each glanced down at her and she, poor thing, was frightened out of her wits to be looked at by so many tall, important-looking people.

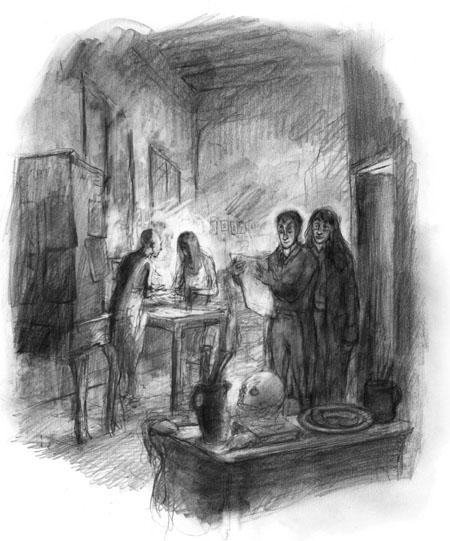

Strange did not trouble to send up his name - it seemed so unlikely that they could have persuaded the little servant-girl to do it. Instead, instructing Childermass to follow him, Strange ran up the stairs and passed directly into one of the rooms. There in an obscure light made by many candles burning in a sort of fog - for the house seemed to produce its own weather - they found the engraver, M'sieur Minervois, and his assistant, M'sieur Forcal- quier.

M'sieur Minervois was not a tall man; he was slight of figure. He had long hair, as fine, dark, shining and soft as a skein of brown silk. It brushed his shoulders and fell into his face whenever he stooped over his work - which was almost all the time. His eyes too were remarkable - large, soft and brown, suggesting his southern origins. M'sieur Forcalquier's looks formed a striking contrast to the extreme handsomeness of his master. He had a bony face with deep sunken eyes, a shaven head covered in pale bristles. But for all his cadaverous, almost skeletal, aspect he was of a most courteous disposition.

They were refugees from France, but the distinction between a refugee and an enemy was altogether too fine a one for the people of Spitalfields. M'sieur Minervois and M'sieur Forcalquier were known everywhere as French spies. They endured much on account of this unjust reputation: gangs of Spitalfields boys and girls thought it the best part of any holiday to lie in wait for the two Frenchmen and beat them and roll them in the dirt - an article in which Spitalfields was peculiarly rich. On other days the French- men's neighbours relieved their feelings by surliness and catcalls and refusing to sell them any thing they might want or need. Strange had been of some assistance in mediating between M'sieur Minervois and his landlord and in arguing this latter gentleman into a more just understanding of M'sieur Minervois's character and situation - and by sending Jeremy Johns into all the taverns in the vicinity to drink gin and get into conversations with the natives of the place and to make it generally known that the two French- men were the prote ge s of one of England's two magicians - "and," said Strange, raising a finger to Jeremy in instruction, "if they reply that Norrell is the greater of the two, you may let it pass - but say to them that I have a shorter temper and am altogether more sensitive to slights to my friends." M'sieur Minervois and M'sieur Forcalquier were grateful to Strange for his efforts, but, under such dismal circumstances, they had found that their best friend was brandy, taken with a strict regularity throughout the day.

They stayed shut up inside the house in Elder-street. The shutters were closed day and night against the inhospitableness of Spitalfields. They lived and worked by candlelight and had long since broken off all relations with clocks. They were rather amazed to see Strange and Childermass, being under the impression that it was the middle of the night. They had one servant - the tiny, wide- eyed orphan girl - who could not understand them and who was very much afraid of them and whose name they did not know. But in a careless, lofty way, the two men were kind to her and had given her a little room of her own with a feather-bed in it and linen sheets - so that she thought the gloomy house a very paradise. Her chief duties were to go and fetch them food and brandy and opium - which they then divided with her, keeping the brandy and opium for themselves, but giving her most of the food. She also fetched and heated water for their baths and their shaving - for both were rather vain. But they were entirely indifferent to dirt or disorder in the house, which was just as well for the little orphan knew as much of housekeeping as she did of Ancient Hebrew.

There were sheets of thick paper on every surface and inky rags. There were pewter dishes containing ancient cheese rinds and pots containing pens and pieces of charcoal. There was an elderly bunch of celery that had lived too long and too promiscuously in close companionship with the charcoal for its own good. There were engravings and drawings pinned directly on to every part of the panelling and the dark, dirty wallpaper - there was one of Strange that was particularly good.

At the back of the house in a smutty little yard there was an apple tree which had once been a country tree - until grey London had come and eaten up all its pleasant green neighbours. Once in a fit of industriousness someunknownpersoninthe househadpicked all the apples off the tree and placed them on all of the windowsills, where they had lain for several years now - becoming first old apples, then swollen corpses of apples and finallymere ghosts of apples.There was a very decided smell about the place - a compound of ink, paper, seacoals, brandy, opium, rotting apples, candles, coffee - all mingled with the unique perfume exuded by two men who work day and night in a rather confined space and who never under any circum- stances can be induced to open a window.

The truth was that Minervois and Forcalquier often forgot that there were such places as Spitalfields or France upon the face of the earth. They lived for days at a time in the little universe of the engravings for Strange's book - and these were very odd things indeed.

They shewed great corridors built more of shadows than any thing else. Dark openings in the walls suggested other corridors so that the engravings appeared to be of the inside of a labyrinth or something of that sort. Some shewed broad steps leading down to dark underground canals. There were drawings of a vast dark moor, across which wound a forlorn road. The spectator appeared to be looking down on this scene from a great height. Far, far ahead on that road there was a shadow - no more than a scratch upon the road's pale surface - it was too far off to say if it were man or woman or child, or even a human person, but somehow its appearance in all that unpeopled space was most disquieting.

One picture showed the likeness of a lonely bridge that spanned some immense and misty void - perhaps the sky itself - and, though the bridge was constructed of the same massive masonry as the corridors and the canals, upon either side tiny staircases wound down, clinging to the great supports of the bridge. These staircases were frail-looking things, built with far less skill than the bridge, but there were many of them winding down through the clouds to God-knew-where.

Strange bent over these things, with a concentration to rival Minervois's own, questioning, criticizing and proposing. Strange and the two engravers spoke French to each other. To Strange's surprize Childermass understood perfectly and even addressed one or two questions to Minervois in his own language. Unfortunately, Childermass's French was so strongly accented by his native Yorkshire that Minervois did not understand and asked Strange if Childermass was Dutch.

"Of course," remarked Strange to Childermass, "they make these scenes altogether too Roman - too like the works of Palladio and Piranesi, but they cannot help that - it is their training. One can never help one's training, you know. As a magician I shall never quite be Strange - or, at least, not Strange alone - there is too much of Norrell in me."

"So this is what you saw upon the King's Roads?" said Child- ermass.

"Yes."

"And what is the country that the bridge crosses?"

Strange looked at Childermass ironically. "I do not know, Magician. What is your opinion?"

Childermass shrugged. "I suppose it is Faerie."

"Perhaps. But I am beginning to think that what we call Faerie is likely to be made up of many countries. One might as well say `Elsewhere' and say as much."

"How far distant are these places?"

"Not far. I went there from Covent-garden and saw them all in the space of an hour and a half."

"Was the magic difficult?"

"No, not really."

"And will you tell me what it was?"

"With the greatest good will in the world. You need a spell of revelation - I used Doncaster. And another of dissolution to melt the mirror's surface. There are no end of dissolution spells in the books I have seen, but as far as I can tell, they are all perfectly useless so I was obliged to make my own - I can write it down for you if you wish. Finally one must set both of these spells within an overarching spell of path-finding. That is important, otherwise I do not see how you would ever get out again." Strange paused and looked at Childermass. "You follow me?"

"Perfectly, sir."

"Good." There was a little pause and then Strange said, "Is it not time, Childermass, that you left Mr Norrell's service and came to me? There need be none of this servant nonsense. You would simply be my pupil and assistant."

Childermass laughed. "Ha, ha! Thank you, sir. Thank you! But Mr Norrell and I are not done with each other. Not yet. And, besides, I think I would be a very bad pupil - worse even than you."

Strange, smiling, considered a moment. "That is a good an- swer," he said at last, "but not quite good enough, I am afraid. I do not believe that you can truly support Norrell's side. One magician in England! One opinion upon magic! Surely you do not agree with that? There is at least as much contrariness in your character as in mine. Why not come and be contrary with me?"

"But then I would be obliged to agree with you, sir, would I not? I do not know how it will end with you and Norrell. I have asked my cards to tell me, but the answer seems to blow this way and that. What lies ahead is too complex for the cards to explain clearly and I cannot find the right question to ask them. I tell you what I will do. I will make you a promise. If you fail and Mr Norrell wins, then I will indeed leave his service. I will take up your cause, oppose him with all my might and find arguments to vex him - and then there shall still be two magicians in England and two opinions upon magic. But, if he should fail and you win, I will do the same for you. Is that good enough?"

Strange smiled. "Yes, that is good enough. Go back to Mr Norrell and present my compliments. Tell him I hope he will be pleased with the answers I have given you. If there is any thing else he wishes to know, you will find me at home tomorrow at about four."

"Thank you, sir. You have been very frank and open."

"And why should I not? It is Norrell who likes to keep secrets, not I. I have told you nothing that is not already in my book. In a month or so, every man, woman and child in the kingdom will be able to read it and form their own opinions upon it. I really cannot see that there is any thing Norrell can do to prevent it."

1

Famulus

: a Latin word meaning a servant, especially the servant of a magician.

2 Sir Walter is voicing a commonly-held concern. Shape-changing magic has lways been regarded with suspicion. The

Aureates

generally employed it during their travels in Faerie or other lands beyond England. They were aware that shape-changing magic was particularly liable to abuses of every sort. For example in London in 1232 a nobleman's wife called Cecily de Walbrook found a handsome pewter-coloured cat scratching at her bed- chamber door. She took it in and named it Sir Loveday. It ate from her hand and slept upon her bed. What was even more remarkable, it followed her everywhere, even to church where it sat curled up in the hem of her skirts, purring. Then one day she was seen in the street with Sir Loveday by a magician called Walter de Chepe. His suspicions were immediately aroused. He approached Cecily and said, "Lady, the cat that follows you - I fear it is no cat at all." Two other magicians were fetched and Walter and the others said spells over Sir Loveday. He turned back into his true shape - that of a minor magician called Joscelin de Snitton. Shortly afterwards Joscelin was tried by the Petty Dragownes of London and sentenced to have his right hand cut off.