Joyce's War (2 page)

Authors: Joyce Ffoulkes Parry

The writing of the journal was remarkably assured: Joyce has a firm and steady hand, even while on night duty under dim light. Inevitably, because of pressure of work, there were gaps of weeks or even months but she often tries to pick up the threads in order to create continuity. Joyce did not alter one word either at the time of writing or subsequently; there are no crossings-out except for one redacted reference to a matron where the censors may have intervened and there are only two notes in the margin. It seems clear that she intended the journal to be read and we know that she re-read it after the war as there are whole pages or passages which are marked with a blue pencil or an asterisk. These are often places which are described vividly in the journal or moments which she might have to wished to recall on cold winter evenings in Swansea in the 1950s.

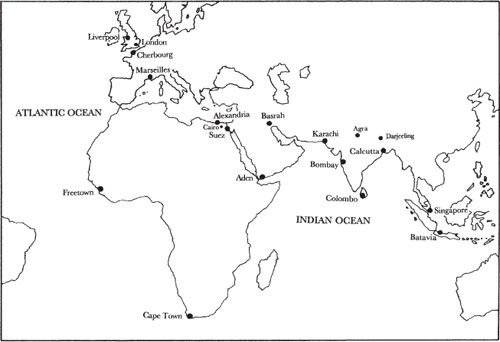

From a practical point of view, editing the journal has entailed the usual challenges of someone else’s handwriting, wartime abbreviations and acronyms. I have transcribed word for word from the two handwritten vellum foolscap notebooks and occasionally added a word to make the sense clearer and I have made some paragraphs shorter. I have added footnotes, where I thought this helped the text; in particular I have sourced the many lines of poetry scattered through the journal. I have left her contemporary names for places she visited unless the name has changed significantly. I have added the following sections: dramatis personae; abbreviations; a map of the principal places; a postscript and index. My sister Siân Bailey has created the illustrations, which capture the mood perfectly.

Editing the journals has inevitably raised questions for me as its editor. Joyce was my mother but she was not my mother when she wrote these journals and her life then was entirely separate from the family life she later created. Is it appropriate that this former life be revealed to the world, even partially? The answer I believe is that she did intend the journal to be read as her record and eyewitness account of the war but she safeguarded herself and others by keeping aspects of her life private. Despite all the hundreds of letters exchanged between Joyce, her family and friends in Australia and Wales, and with Ken, Bob and David, sadly not one has survived. There are, however, eight letters from an envelope marked ‘Letters’ from other times, including from writers with whom she corresponded during the war. Her registration and call-up papers have been retained and there is also a full set of payslips together with correspondence with the War Office recording the saga of the non- or mis-payment of her salary. There are four war medals in their original box and albums containing some hundreds of photographs taken with her box camera.

Joyce comes through as a brave, loyal and independent-minded woman committed to fairness and justice, whose experiences of places, people and events are recorded vividly because she loved to write. Her dry sense of humour and her irony are refreshing: ‘This morning I packed an emergency bag in case of “abandon ship” – two actually: one with essentials … the other with as much of my new undies as I can stuff in and which I have no intention of resigning to the fishes.’ Her compassion for her patients shines through together with her own modesty. She reflects on 22 May 1941:

If by some chance I should become a war victim too … I should hate to think my name was inscribed on a brass roll of honour – as though I were some heroine – which emphatically I am not, and should be perfectly happy knowing I had done my job according to my own standards – although they may be a little odd at times.

Rhiannon Evans

2015

Many people are mentioned in the journal but below I have listed the people who are mentioned most often or where additional information has come to light. Unfortunately it has not been possible to trace many of Joyce’s friends and colleagues:

Australia

Rev. Robert and Annie Ffoulkes Parry

, father and mother, Ballarat, Victoria, Australia.

Glyn

, brother, wife Edna and son Bruce (b. 1941).

Mona

,

sister.

Clwyd

, brother.

Major-General Robert Ernest Williams

, CMG, VD, State Commandant for Victoria and editor of the Ballarat

Courier.

Joyce was his private nurse until she left Australia to travel to the UK in 1937 and they corresponded throughout the war.

Jean Oddie

and

Enid Baker

,

schoolfriends who were also nursing in the ME where they met with Joyce from time to time.

Wales before the war

Gwen Roberts

, first cousin and also nursing colleague in France, but Gwen elected to stay in the UK when she married Ronald.

Mali Williams

, a good friend from 1937. She lived with her mother Mrs Williams and her sister Gwerfyl in

Old Meadows

, Deganwy, North Wales. Mali corresponded with Joyce throughout the war and frequently sent her books and literary journals. They remained friends after the war, corresponding frequently until Mali’s death from cancer in 1951.

Ruthin

, referring to second cousins Mabel and Bert, whose names are not mentioned but who lived in Ruthin, North Wales.

On board HTS

Otranto

Mona Stewart

, who registered as a QA at the same time as Joyce; they were companions, colleagues and friends throughout the war. Mona married

John Newman

. Mona also served on HMHS

Karapara

.

Bill Williams

, a fellow Australian, from Adelaide, whom Joyce met in London in 1940; they were together in France and Alexandria. She married a naval captain in 1941 but died of cancer at a young age.

On board HMHS

Karapara

Major T.C. Ramchandani

, Chief Medical Officer in 1942. He was bundled off

Karapara

in 1944 on a stretcher after twenty-one days of enteritis had reduced him to a skeleton. He recovered and served the rest of the war in India and Burma. He wrote to Joyce after the war, thanking her for her support to India and independence.

And …

Kenneth Hannan Stanley

, to whom Joyce was engaged from July 1941 until September 1942. He was in 5th Indian Troop Transport Corps and in Cyprus. He married Sheila Allen, an Assistant Installation Superintendent, in December 1946 at Rawalpindi, India.

Bob

, a good friend. Stationed in Basrah and possibly an army doctor.

David Herbert Davies

, Joyce’s first husband. Joyce married David (or Dafydd as she called him) in May 1943 at St Andrew’s Church, Calcutta.

ABBREVIATIONS USED IN THE TEXT

AC1 | Aircraftsman Class 1 |

A/C | Air Commander |

ADMS | Assistant Director Medical Services |

AGH | Australian General Hospital |

AIF | Australian Imperial Force |

AN | Australian Navy |

BA | British Army |

BI | British Information / Intelligence |

BGH | British General Hospital |

BMH | British Military Hospital |

BORs | British Other Ranks |

CB | Confined to Barracks |

CCS | Casualty Clearing Station |

CIW | Clinical Investigation Wing |

CO | Commanding Officer |

DDMS | Deputy Director Medical Services |

DIL | Dangerously Ill List |

FC | Field Cashier |

HMAS | His Majesty’s Australian Ship |

HMT | His Majesty’s Troopship |

ICC | Indian Casualty Clearing Station |

IGH | Indian General Hospital |

IMS | Indian Medical Service |

JOLs | John O’London’s |

ME | Middle East |

MEF | Middle East Forces |

MO | Medical Officer |

NAAFI | Navy, Army & Air Force Institute |

NYD | Not yet diagnosed |

NZ | New Zealand |

OMO | Orderly Medical Officer |

OTC | Officers’ Training Camp |

PO | Principal Officer |

POW | Prisoners of War |

PM | Post-Mortem |

QA | Queen Alexandra (nurse) |

RAMC | Royal Army Medical Corps |

RAMS | Royal Army Medical Services |

RASC | Royal Army Service Corps |

RRC | Royal Red Cross |

RTO | Railway Transport Office/r |

SRMO | Senior Royal Medical Officer |

STO | Senior Technical Officer |

TAB | Typhoid and Para-Typhoid Inoculation |

QAIMNS(R) | Queen Alexandra’s Imperial Military Nursing Service (Reserve) |

VAD | Voluntary Aid Division |

VD | Venereal Disease – now called sexually transmitted diseases/infections |

JOYCE’S WAR

Wales – London – France – Troopship

Otranto

– Egypt Cairo – Alexandria British General Hospital

August 6th 1940

Onward bound for the Middle East

on board HMT Otranto

At sea … somewhere north of Liverpool, the Irish coast to the left and the Scottish to the right. We embarked on Saturday, leaving London Euston at 6.30am, having gone to bed at 3.30am the same morning and arisen at 4.30am. I slept most of the journey to Liverpool. We had hopefully thought of some hours at large in Liverpool to finish our endless shopping, but we were run out to the docks, in the train, and then after standing with our hand luggage on the platform for an hour or so, we were hustled onto the boat – the

OTRANTO

– all set for the first stage of adventure. After some reshuffling Mona Stewart and I are able to share a cabin together which is very small – I practically have to retire to bed to let Mona dress and vice versa. The chair and the ladder are the only moveable pieces of furniture and they have to be removed before we can turn around.

We manage somehow, however, with the two cabin trunks under the bunks and the coal scuttle which serves as a blackout – later on – under the washbasin, the surplus blankets and rugs somewhere on rafters under the roof, the cases along the lobby and the remainder where it will best fit. There is so far no water in the cabin so we have to trek upstairs to the ‘ladies’ where there are neat rows of washbasins and plenty of cold water but no hot water, nor will there be, we are told, for the duration of the voyage. This is very sad because we shall have to do our washing in cold water. We can have hot sea water baths but no fresh water hot baths. At present the scene in the bathroom morning and evening is a fair replica of any Grecian frieze: beauty in varying stages of unadornment, a new angle of the QAIMNS(R)

2

but hardly for publication!

Monday. We left under cover at 10pm and were allowed on deck to see the sights. It was dark, or nearly so; the English coast to the right as we went upstream, and the coast of my beloved Wales on the left. The dim outline of ships, in irregular procession – 12 we were told – several destroyers in front of us and behind us, and a torpedo last, painted in black with seven white stripes like a zebra, and probably other protecting craft that one can’t see. In any case we retire to bed feeling quite safe and think no more at all that we are on the sea, and that there is a war on, and that we are involved. This morning the usual boat drill and a conference about what we may do or not do. And now I am at long last attempting to write a resume of what has happened since I joined up, or rather was called up last March. For this I need to go back a few months.