Joyland (29 page)

The machine had the vocabulary of a second-grader, could only spell words that were foreign or unrecognized. Slang. People’s names. Anything beyond two syllables, the computer walked into a psychological wall. “Hello, T-A-M-M-Y.”

Occasionally, Mrs. Lane’s head bopped up and down past the window. The grating of Mr. Lane’s scraper on the garage supplied a guide to their locations. Tammy monitored her mother, as if her mother were Evil Otto stationed outside the house. Inside, Tammy navigated the things the computer did and did not understand.

“S-H-I-T-heaaaad,” the computer clipped without anger or emotion. White letters on a blue background. “Suck my dictionary.” The screen glowed. The blue-green light was tropical and sweet.

The clock on the wall burst open. Above its brown leafy dial, a door opened and a tuft of feather sprang in and out. Twelve. The

cuckoo

was skewed and metallic, followed by the quiet ringing of bells.

A whole hour had passed in nuggets of ad-libbed profanity. She’d missed all of

The Price is Right.

There was nothing on now but

The

700

Club.

“Screw off.”

Tammy rocked back and forth on the stool, folded a leg across her lap and pressed one heel under herself.

“Eat me,” the speaker belched without the slightest quiver — a phrase Tammy had only seen painted on walls.

She clasped her hands over her mouth.

“Eat me,” the computer said again, and “eat me,” its voice never changing.

Between the four lavender walls of the bathroom, an assessment was quickly made regarding how such a thing was done. That cow head in the diagram. The

vagina

. One, two, three. That was how they went, in pale pink circles on glossy white paper, slim black vector lines leading to their names.

Clitoris, urethra, vagina.

Easy. One, two, three . . . It didn’t feel like anything. Tammy shifted. Tammy shifted. Tammy shif — then she felt it.

It gave way like a jet of hot water.

When she looked down, she had not achieved some state of pleasure. She had broken her hymen, a firewall wafer of skin.

Its descent drummed a shock through her and she froze. The muddy lot of it sunk into the fabric of her clothes. Her limbs went shivery. She didn’t catch her breath, it caught her, jabbed a fist in her chest. She hiccupped, made a mad grab for a swatch of toilet paper. Against the white cotton, the blood was like oil, like car grease.

Tammy sat stiffly at the computer. She typed the most banal of phrases into its cold blue face. “T-A-M-M-Y is greaaaaat.” On the couch behind her, Mr. Lane sat with his mug. His shirt was hooked limply over the arm of the couch. Next to the back door, his shoes were spotted with paint.

“Hoo boy,” he huffed, “it’s a scorcher out there, it’s a scorcher.”

She had no idea if her mother had told him. She entered womanhood, two years and a lie early, sitting tight-kneed around a Kleenex.

“Going to the drug store,” Mrs. Lane announced from the kitchen doorway, worrying the car keys from a side pocket in her purse. Tammy cringed into the keyboard.

That was when phone rang.

Mrs. Lane answered. “Yes,” she said, “yes” and “yes” again, a jolt in her voice.

When she put the receiver down, she began to tell them. Her mouth moved, but there were no words. The room had freeze-framed. It began to slide out of place in a transition of neon as Mr. and Mrs. Lane moved from one room to the next.

A fight, the Bretons, an older boy, Chris. Dead. The words formed a wall around Tammy as she stood very still next to the doorway. Her head throbbed with the bits of data. She dropped to the living room carpet, clasped her arms around her knees, pressed chin to shins, rocked, Kleenex in her crotch forgotten.

She knew without being told. She shivered. It was Adam, the Rabbit, the pool man. It was the girl in the Sunset Villa, the girl he shouldn’t have gone to see. It was the cigarette behind the arcade. It was a long series of

it

s without a proper file for information storage. The nubby carpet gnawed from beneath her socks, beneath her nylon shorts when she tipped back, beneath her. She was back on the ground, the carpet squirmer, this time more foetal than frottaging. Across the den, the piano’s foot-rubbed wood stared at her. In the other room, her parents stood in the dip in the lineoleum where a marble or a HotWheels would stall, behind a door with a crack wide enough to slip a doll’s shoe under.

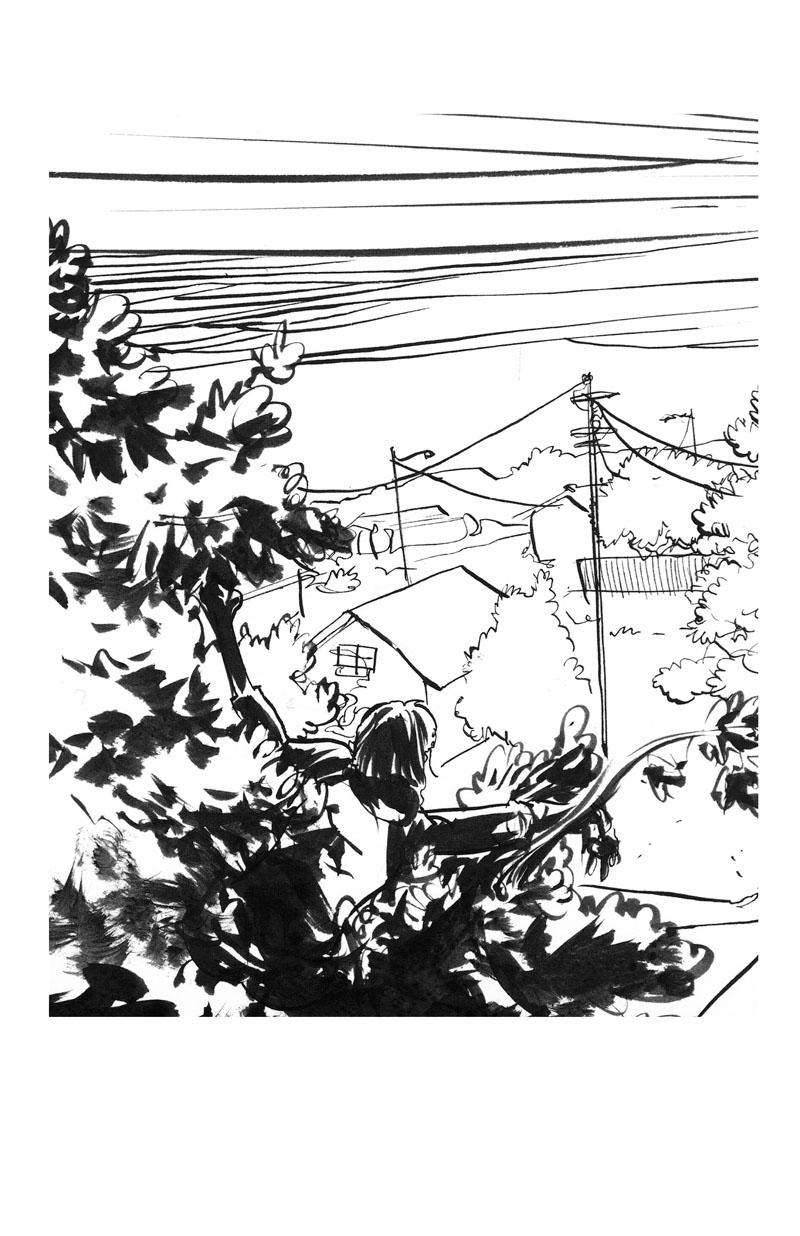

She didn’t take her bike. That would have meant going the back way, past the kitchen window. Without it, she was unencumbered, slipping quietly out the front door, the screen easing shut between pinched careful fingers, the head of the handle memorized for all time in those few seconds. Its ridged palm-sized square of silver teeth.

Tammy took a few slow steps, then ran, grass padding the sound, the thud of hard August mud beneath purple Kangaroos. She beelined across the VanDoorens’ lawn. From the corner of Running Creek she could see nothing, no yellow police ribbons, no ambulance cherry glinting. She flew over Mr. Sparks’ shrubbery like a steeplechase steed and snipped the head of a tiger lily off its stalk as she landed on the other side, still galloping. She landed in a blotch of blood, eventually. Her sneakers passed across it before she even saw the stain.

It was here, here.

She looked all around the crescent, the Bretons’ house like a strange gold tooth, and all the white houses surrounding her still smiling with roses, still yawning garage doors. No one was there, rushing about, weeping, distraught, gossiping. Nothing out of the ordinary. Tammy turned in all directions, then looked down at the single remaining piece of colour. She had no way to document it. The evidence.

Sudden, automatic, a sprinkler turned on, hissing, spun like a gear in a jewellery box with the ballerina pulled off. With its intrusion, Tammy jumped, the colour smearing beneath her shoe.

She bent down, touched it. Immediately self-conscious, glancing at glinting windows, she pretended to tie her shoe. She took a pebble from the scene, pushed it down inside the lip of her sneaker, sprinted home again on top of its jagged stone eye. The blood on it brought her blood to the surface, a small blister rising inside the perfect arch of her white sock.

PLAYER 1

Chris saw his father before his father saw him. Across the station. Through the glass frames in police reception. In profile, Mr. Lane had the presence of a pit bull. Years of weight training had left his short body broad and mean, his shoulders wider than he seemed tall. In comparison to the towering officer, he appeared dwarfed, but no less spry. He had the broad, muscled hands of a machinist. One rested upon his hip, the other on the counter, crooked, fingers flexed. Chris imagined the strained conversation through the half-brick half-glass wall that separated them.

“I’m here for my son.”

“Which one is he?”

“Christopher Lane. Lane, L-A-N-E.”

“Lane,” the officer called when he came to get him. But Chris was already on his feet.

As they walked down the hall and out the front doors, Mr. Lane’s basketball shoes squeaked against the fake marble. They didn’t speak. On the stairs outside, Mr. Lane stopped. He grasped the large brick wall that ran around the landing and down the wide steps, half-sat upon it, his body visibly shaking.

Chris stared down at the three stripes on either foot that thrust out in front of Mr. Lane, paint-pocked Adidas.

“Chris?” There was a rough question mark in it.

Mr. Lane folded the matchbook backward and pulled the match out from between the two flaps. It flared with a bright

psssst

. He stared at Chris above the cigarette that stuffed his mouth. The end of it glowed, and he held the breath in for a long time before blowing the smoke out. It drifted across to where Chris stood waiting. Around them, South Wakefield was alive and iridescent, sky and grass, rich blue and green, obscenely Norman Rockwell.

Mr. Lane’s fingers curled into a fist that knocked firmly upon the top of the stone ledge. Chris stared at it, knowing what he had earned. Mr. Lane glared across the parkette in front of the police station. His mouth opened and closed. He rapped his knuckles again against the stone, loosening a small chunk of skin. A small ragged red circle remained and the tip of the filter glowed. That cigarette was all that stood between Chris and his father. It burned and blew its way out again.

PLAYER 2

Mr. Lane strode across the porch steps as if he couldn’t get away from Chris fast enough. Tammy watched her father through the sheers. In front of her, Mrs. Lane also stood watching. Her fingers bunched and unbunched a tense white handkerchief, acquired during Tammy’s brief absence.

Mr. Lane stopped suddenly in front of the living room window, looked in at them. Chris — who hadn’t raised his head since exiting the car — bumped against him.

Mr. Lane’s hand came around, settled on Chris’s shoulder for just a second. Mr. Lane’s mouth loosened as his eyes fastened on his wife, what Tammy knew, even from behind, was her mother’s pinched, skinny mouth. Tammy’s father clapped Chris on the shoulder, wrapped his fingers around the tendon, perhaps to steer him into the house, perhaps for comfort. She had no idea that it was the first time they had touched in over a year.

He gripped Chris, solidly, as she had seen men do to one another earlier that summer at her grandfather’s funeral, broad palm stranded between affection and violence. Even then, it had struck her that they were bracing one another for something so large they couldn’t quite wrap their whole hands around it, or stand to touch it in any other way. Isolation, anger, pain. Things grown men did not have words for, but could only clap out of one another temporarily.

Chris stumbled under his father’s touch, his eyes meeting Tammy’s through the window, dull with sullen absence. For the first time in her life, more than a few feet and a wall or a sheet of glass divided all of them.

Flap, flap. Flap, flap.

She watched her brother swallow under the weight of it.

Then the hand rose up and flew away.

The moiré pattern of the sheer curtain cast a strange haze across the picture. Even as Mrs. Lane reached to sweep it aside, Chris’s face wavered. His dark eyes skipped between Tammy and his mother before they dissolved into static. Both sides of the screen blipped and broke into infinite fuzz.

BONUS

PLAYER 2

Tammy the Spy cruised down St. Lawrence Street, dipped into the crescent where the Bretons had lived. There was a new family there now — just since the weekend — and she took every possible opportunity to try to catch a glimpse. Today, the windows were dark. A large rubber skeleton hung on the door. The plastic ripped apart, serrated and stringy. Dark wood showed behind its jangled bones. Its yellow neon ribs sent a quake of happiness through Tammy’s chest. A white elastic thread held up Tammy’s heart. She looped her bike in a circle, three times. It meant they had kids.

In early September, Chris and Tammy had watched a tow truck cart away Mr. Breton’s chipped crash-derby cruiser. The Lane children were sitting on the curb together, an old tennis ball making a grey-green journey in and out of Chris’s palms. The police-painted black-and-white hood rumbled up alongside and passed them — disappeared down the road, the signal beside the burst headlight blinking as its porter lumbered around the corner onto St. Lawrence Street. The ball stopped, and Chris was gone, off and running, into the house. Tammy sat on the curb with the tennis ball in her brother’s place. She bounced it gently against the concrete and didn’t look over her shoulder at her brother’s bedroom window.

Mrs. Breton had taken J.P. to live with relatives in Quebec. Apparently, she and Mr. Breton had been on the verge of splitting anyway. The incident had allowed everything to fracture.

Separation was like that, apparently. One day everything seemed fine. The next day, people were gone. Tammy shrugged it off like a bad dream. There was no point in thinking about it; it just

was

. Her parents were still solid. She stopped waiting for the fission. Instead, she dodged in and out of driveways, swerving her bicycle to and fro over the abandoned road.