Julia Child Rules (14 page)

Authors: Karen Karbo

The story has been told many times, how Julia and Simca delivered an unwieldy behemoth, not the smart French cookbook geared for the American housewife/chauffeur that Houghton Mifflin had contracted for, but a mad, not to say obsessive, compilation of every sauce and poultry recipe in the known French culinary universe. Still to be addressed were eggs, vegetables, fish, meat, and desserts. In a letter to Avis, Julia wrote, “We intend to take an attack position. That this is the type of series of books we plan to do, and that Volume II will be ready well within a year of the publication of Vol. I; and that Volume III will be ready within about six months of Volume II. This is going to mean hard and constant application but we feel it must be done …”

Houghton Mifflin did not feel the same, and it was a good thing, too. Eight hundred pages of sauces and poultry? As Dorothy de Santillana pointed out in her respectful rejection letter, length aside, the two don’t have anything in common, aside from the fact that Julia and Simca happened to focus on those sections first. Oh, I know. The romance of this kind of saga demands that the suits get a bad rap for thinking only of the bottom line, for quashing Julia’s creative integrity and genius, but the meanies and the pencil pushers aren’t always wrong. Houghton Mifflin saved Julia from herself and helped her to refocus. In case there’s any doubt, after Julia became the most famous cook in America, with a spate of best-selling cookbooks and a hit TV

show, with Emmys, honorary doctorate degrees, and a running spot on

Good Morning America,

did she call Judith Jones on her private line at Knopf and say, “We must publish an eight-hundred-page book on sauces and poultry?” No, she did not.

Her letter acknowledging the rejection letter was determinedly upbeat, her attack position abandoned. She acknowledged that what she and Simca had slaved away on was not what they’d been contracted to do, and that they were prepared to write a “short and snappy book directed to the somewhat sophisticated housewife/chauffeur” of about three hundred pages that would include “unusual vegetable dishes including the pepping up of canned and frozen vegetables” and, hopefully, even “insert a note of gaiety and a certain quiet chic.”

Julia was frustrated and heart-bruised. Avis, who never lost the faith, consoled her with the truth that nothing we learn ever goes to waste, and that someday her work would pay off.

It could not be said of Julia that she was no quitter. She’d quit quite a few things in her time. At Smith she quit the basketball team when it was obvious she wasn’t the star her mother had been. She quit the Packard Commercial School after a mere month,

*

quit her good job at W. & J. Sloane and New York City entirely after she’d been jilted by Tom, her literature major boyfriend. Julia’s passion and sense of theatrics cut both ways; she could throw herself out of something as easily as she could throw herself into it.

There was no reason why she shouldn’t have quit The Book, too. Why persist? The project had occupied her time, given her a sense of purpose, and enriched her life beyond measure, while Paul was overworking at his various embassies. Creating The Book had given her a

métier

and a

raison d’être,

words that find feeble translation in English. Also, unlike writing an eight-hundred-page novel that no one wants, the recipes you’ve created for a cookbook are useful. You still have to eat. It’s the nature of cookery-bookery that several times a day you can still practice the thing that inspired you to want to write a cookbook in the first place. Indeed, for people who have a tortured ambivalence about cooking, the exact same thing plunges us into Sisyphean despair, that not ninety minutes after we’ve cleaned up after one meal it’s time to start preparing the next one. But this is cause for great joy for a devoted foodie like Julia. She and Paul would still need to eat, and she could still cook up a storm, dirtying every copper pot in the place. That would never change.

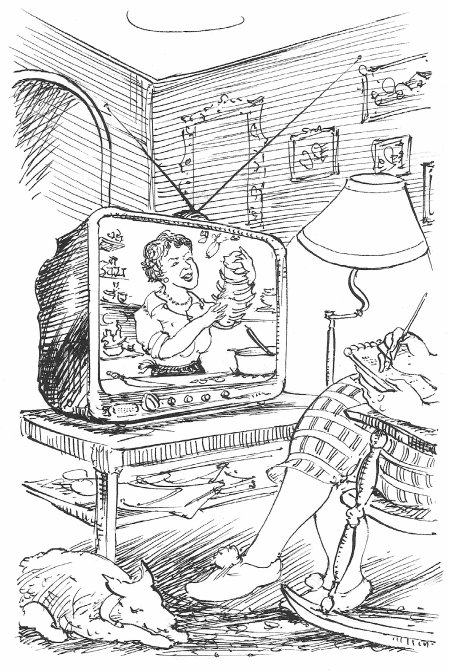

It couldn’t have helped her frame of mind to witness firsthand the state of American cuisine. She and Paul had been abroad for many years, and they had only heard about the invasion of entire frozen meals that were served in the compartmentalized tin tray in which they were heated and then consumed on trays in front of the television. Julia and Paul didn’t own a television, nor had they ever watched it. Craig Claiborne, the then-new food editor and restaurant critic for the

New York Times,

bemoaned the state of cooking in America.

At any rate, life was moving on. Paul had just accepted a posting in Norway, at the Cultural Affairs Office in Oslo. Publicly she was grateful for the posting—Paul needed to work, and this was a promotion—but Julia sobbed in private at the thought of packing up her

batterie de cuisine

and leaving her new gas range, the dishwasher, and pig in the sink for another tiny kitchen in another foreign country that was not France.

The obvious lesson in all this, knowing how it all turned out, is that when faced with a setback of this magnitude, there is nothing for it but to pick yourself up, dust yourself off, and soldier on with renewed determination to succeed! If only it were that easy. Julia was in a funk. How did she manage to persevere, turning a stupendous failure into a groundbreaking success?

Keep trying, keep failing.

Paul and Julia sailed for Europe on the SS

United States,

stopping in France for a few days to indulge in a bilious-inducing tour of their favorite restaurants and see old, beloved friends. Julia’s first friend in Paris, Hélène Baltrusaitis, had just organized a special exhibit at the US Information Agency (USIA), Paul’s old haunt: “The Twenties: American Writers in Paris and Their Friends.” Julia and Paul missed the exhibit by a few days, but not the chance to make the acquaintance of Sylvia Beach, owner of Shakespeare and Company and publisher of

Ulysses

. If anything could coax the famously reclusive playwright Samuel

Beckett from his hidey-hole on the rue des Favorites, it would be a celebration of his beloved James Joyce.

Until the end of her long life, Julia was never afraid to seek the advice of experts.

In all the Western world, no one was a bigger expert on failure than Beckett. If Julia was happiest in the kitchen, the author of

Waiting for Godot

was happiest in the pit of despair. Who better, then, to advise her on how to go on when you simply couldn’t go on?

They met for dinner at La Closerie des Lilas on Boulevard du Montparnasse and sat on the lamp-lit terrace. Since it was spring, chances are it was depressing and gray, just the kind of weather Beckett preferred. Inside, the same piano player who entertained Hemingway, Picasso, Apollinaire, and all the rest, played his old standards. The two feasted on escargots with garlic and parsley butter, duck foie gras terrine, steak tartare, and white asparagus. They enjoyed one of those beautiful, perfectly matured Bordeaux that made Julia swoon.

Beckett, who resembled a bird-of-prey, with his large, bony nose and thick, cowlicky, stand-up gray hair, was known to be a man of few words. But Julia wielded her polecat-charming genius and had him waxing philosophical before the end of the first course. He nodded sagely—also something at which he was an expert—as he listened to her tale of cookery-bookery woe, then reminded her that as long as you take even one step forward you haven’t failed.

Success was complicated, he said, but failure is easy. All you had to do was keep going, one step at a time. All you had to do was solve the problem in front of you.

“Try again. Fail again. Fail better,” he said, over the cheese course.

Of course, this meal is a figment of my butter-addled imagination. This meal never happened, or not that any of the Julia scholars know of, but given how Julia proceeded, it might have. She spent the last two days in Paris working with Simca, who was recovering from an attack of gout, on a failed recipe for

jambon en croûte,

determined to give Houghton Mifflin a cookbook they would be proud to publish.

Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

Given Julia’s dedication to doing things right, her passion for teaching, and her aversion to shortcuts, she was never going to be able to produce the “short and snappy” three-hundred pager she promised Dorothy de Santillana. Even if she could do it, there’s every chance that Avis, who was not only her best friend, confidant, and mentor, but also an important publishing-world contact, would not have let her.

Avis was that outlier, the most excellent housewife-chauffeur, and Julia’s perfect reader. Without Avis, there could have been no Julia Child, The French Chef. Houghton Mifflin was DeVoto’s publisher, and it was Avis who hooked Les Trois Gourmandes up

with Dorothy Santillana, but her greatest gift was guiding Julia so that her zeal didn’t get in the way of her message.

Julia loved French cuisine only a smidge less than she loved Paul: the discipline it required and the respect it demanded, but she was also, at heart, a populist. She wanted the people most disparaged by the world of gastronomy—American housewives—to have a shot at making something great to eat. She was on a mission to demystify French cuisine. She was Toto, pulling away the curtain to reveal the Great Oz.

Despite her dedication to process, about taking the proper amount of time and never heeding the siren call of shortcuts, Julia was never a food snob. Once, when she and Paul were living in Germany, they made a trip back to the States, and she claimed the only good thing she ate was a foot-long hot dog with sauerkraut. When they moved back to the States, for good, settling not far from where Avis lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Julia went on record as saying the only thing wrong with McDonald’s was that they didn’t serve red wine.

In editing the original book-length chapter of sauces and poultry, Julia struggled to simplify, while still being thorough. She’d gotten the message, finally, that for someone who wasn’t naturally and perpetually high on life, love, cooking, and Paris, her recipes could be a lot of work, especially since her potential readers suffered a dilemma completely foreign to French women: having to bust ass in the kitchen while being expected,

at the same time, to float among their guests, the serene hostess. Even when she and Paul remodeled their kitchen in Georgetown, she refused to entertain the notion of installing a professional stove, because she knew her housewife audience would never own such a thing. To that end, she tried to structure her recipes so that some steps could be done in advance.

Avis was a genius at helping Julia strike the right balance. Reading the first draft Avis made a note, “I have a strong impression that very few American butchers these days know how to pull tendons.” Yet she also encouraged her not to dumb down the book: “Use finesse as often as you like—once you have explained what it means once or twice.”

Julia and Simca put their heads together and spent another year culling, rewriting, and simplifying. Sauces and poultry needed only to be edited; sections on fish, meat, vegetables, entree and luncheon dishes, cold buffet, and desserts and cakes were brand new. They argued, sometimes bitterly. Simca, in her

La Super-Française

–mode, shrieked at the idea of using a canned or frozen vegetable in even one recipe.

Most of the work was done while Julia was in Oslo, where she was reminded of her mission every so often. Once, at a luncheon for embassy wives, they served for the main course a “salad” made of pink mayonnaise, frozen strawberries, peaches, dates, and bananas with whipped cream—a lone piece of iceberg lettuce peeped out from underneath—followed by a piece

of banana cake from a mix, with thick lard frosting. Julia snorted and declared it a “triumph of Norwegian/American

McCallism

,” after the magazine that rejected her recipes.

When she wasn’t involved in her cookery-bookery or teaching one of her cooking classes (she ran two, with eight students each), she and Paul hiked and skied. She found Norway and the Norwegians to be “nifty.” She devoted herself to learning Norwegian, and by the time she left she could read it and could understand half of any given theater performance. She dutifully practiced with her cleaning lady and the shopkeepers but despaired a little because her Norwegian friends all spoke English.

Finally, in September 1959, the new version of the cookbook was ready. Julia’s promise that it would be a short, snappy three hundred pages was made by a distraught, exhausted author desperate to fulfill her contract and salvage something from her years of long hard work. It was never going to happen. In preparation for submitting the new, slimmer seven-hundred-and-fifty-page manuscript, Julia wrote a letter explaining: “Good French food cannot be produced by zombie cooks,” she said, “one must be willing to sweat over it.”

It took only two months for Houghton Mifflin to reject it again.

She then sent the following letter:

Dearest Simca and Avis,

Black news on the cookbook front … The answer is NO, Neg, Non, Nein … too expensive to print, no prospects of a

mass audience … We must accept the fact that this may well be a book unacceptable to any publisher, as it requires work on the part of the reader …

Julia was beginning to loathe the housewife-chauffeur, the chauffeur–den mother, whatever they wanted to call this apparently lazy, easily intimidated, yet powerful, creature to whom commerce was in thrall. She licked her wounds by throwing herself into learning about French pastry, heretofore her weak spot.

But Avis, who had worked as a book scout at Alfred A. Knopf, had already sent it to a senior editor named Bill Koshland, who passed it on to a junior editor named Judith Jones. Both of them were the rare book people who loved to cook. Persevering is often not simply a matter of working hard and refusing to quit; often, by trying again, failing again, and failing better, we inadvertently place ourselves in the way of luck. Yet another reason to keep on keeping on.