Julius

Authors: Daphne du Maurier

Julius

DAPHNE DU MAURIER

Hachette Digital

Table of Contents

VIRAGO MODERN CLASSICS 506

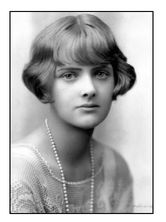

Daphne du Maurier

DAPHNE DU MAURIER (1907-89) was born in London, the daughter of the famous actor-manager Sir Gerald du Maurier and granddaughter of George du Maurier, the author and artist. A voracious reader, she was from an early age fascinated by imaginary worlds and even created a male alter ego for herself. Educated at home with her sisters and later in Paris, she began writing short stories and articles in 1928, and in 1931 her first novel,

The Loving Spirit

, was published. A biography of her father and three other novels followed, but it was the novel

Rebecca

that launched her into the literary stratosphere and made her one of the most popular authors of her day. In 1932, du Maurier married Major Frederick Browning, with whom she had three children.

The Loving Spirit

, was published. A biography of her father and three other novels followed, but it was the novel

Rebecca

that launched her into the literary stratosphere and made her one of the most popular authors of her day. In 1932, du Maurier married Major Frederick Browning, with whom she had three children.

Besides novels, du Maurier published short stories, plays and biographies. Many of her bestselling novels became award-winning films, and in 1969 du Maurier was herself awarded a DBE. She lived most of her life in Cornwall, the setting for many of her books, and when she died in 1989, Margaret Forster wrote in tribute: ‘No other popular writer has so triumphantly defied classification . . . She satisfied all the questionable criteria of popular fiction, and yet satisfied too the exacting requirements of “real literature”, something very few novelists ever do.’

By the same author

Novels

The Loving Spirit

I’ll Never Be Young Again

The Progress of Julius

Jamaica Inn

Rebecca

Frenchman’s Creek

The King’s General

The Parasites

My Cousin Rachel

The Birds and other stories

Mary Anne

The Scapegoat

Castle Dor

The Glass Blowers

The Flight of the Falcon

The House on the Strand

Rule Britannia

The Rendezvous and other stories

The Loving Spirit

I’ll Never Be Young Again

The Progress of Julius

Jamaica Inn

Rebecca

Frenchman’s Creek

The King’s General

The Parasites

My Cousin Rachel

The Birds and other stories

Mary Anne

The Scapegoat

Castle Dor

The Glass Blowers

The Flight of the Falcon

The House on the Strand

Rule Britannia

The Rendezvous and other stories

Non-fiction

Gerald: A Portrait

The Du Mauriers

The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë

Golden Lads

The Winding Stair: Francis Bacon, His Rise and Fall

Myself When Young

The Rebecca Notebook and Other Memories

Gerald: A Portrait

The Du Mauriers

The Infernal World of Branwell Brontë

Golden Lads

The Winding Stair: Francis Bacon, His Rise and Fall

Myself When Young

The Rebecca Notebook and Other Memories

Julius

DAPHNE DU MAURIER

Hachette Digital

Published by Hachette Digital 2010

Copyright © The Estate of Daphne du Maurier 1933

Introduction copyright © Julie Myerson 2004

Julie Myerson asserts her right to be identified as the author

of the Introduction to this Work in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored

in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form

or by any means, without the prior permission in writing

of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of

binding or cover other than that in which it is published

and without a similar condition including this condition

being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

eISBN : 978 0 7481 1460 3

This ebook produced by JOUVE, FRANCE

Hachette Digital

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

An Hachette Livre UK Company

Introduction

I remember exactly who I was when I first read

Julius

. Winter of ’73 and a skinny, bookish thirteen-and-a-half-year-old is lying on the floor of her lilac-wallpapered bedroom in Nottingham. Last week she took

Frenchman’s Creek

out of the library, the week before that

Jamaica Inn

- she was transported by the pure Cornish romance and excitement of them. Now here’s another Daphne du Maurier, one she hasn’t even heard of, fat and promising in its yellow, polythene-wrapped Gollancz cover. She flings herself down on the prickly nylon carpet and opens it enthusiastically.

Julius

. Winter of ’73 and a skinny, bookish thirteen-and-a-half-year-old is lying on the floor of her lilac-wallpapered bedroom in Nottingham. Last week she took

Frenchman’s Creek

out of the library, the week before that

Jamaica Inn

- she was transported by the pure Cornish romance and excitement of them. Now here’s another Daphne du Maurier, one she hasn’t even heard of, fat and promising in its yellow, polythene-wrapped Gollancz cover. She flings herself down on the prickly nylon carpet and opens it enthusiastically.

And is plunged straight into a harsh and remorseless world of Paris under siege, starving peasants, Algerian child prostitutes, ruthless sex, cold murder and emotional sadism. I was, by then, quite a mature reader, but I’d never alighted on a novel as psychologically savage and uncompromisingly sophisticated as this one.

Of course at thirteen, I was far too inexperienced to glean many of

Julius

’s deeper and darker meanings. I knew nothing of men-female sexuality, still less of money, class, deprivation and war. I am sure that back then in my adolescent bedroom, I read this singularly dramatic tale on a very superficial, one-note level. But the gist of it lingered - stayed with me right into adult-hood. All those years, at the back of my mind, I certainly remembered Julius - the uneasy flavour of him, his astounding capacity for money-making, his stark incapacity for anything approaching spontaneous human love. I think I knew even then that those pages contained the portrait of a monster, somehow all the more alarming for being emphatically, or at least, ambivalently, drawn.

Julius

’s deeper and darker meanings. I knew nothing of men-female sexuality, still less of money, class, deprivation and war. I am sure that back then in my adolescent bedroom, I read this singularly dramatic tale on a very superficial, one-note level. But the gist of it lingered - stayed with me right into adult-hood. All those years, at the back of my mind, I certainly remembered Julius - the uneasy flavour of him, his astounding capacity for money-making, his stark incapacity for anything approaching spontaneous human love. I think I knew even then that those pages contained the portrait of a monster, somehow all the more alarming for being emphatically, or at least, ambivalently, drawn.

There’s something calculated and frightening about this book. It’s intensely shocking in places. Its moments of violence and cruelty have, even today, more than fifty years on, an almost David Lynch-style kick to them. This is a tale of such emotional brutality and moral dislocation that it feels as if it’s been wrought by a master, someone who has seen, known and grappled with the world. Chilling, then, to discover that Daphne du Maurier was just twenty-six years old when she wrote it.

So what did this young woman believe she was writing? Is

Julius

a straightforward account of a monstrous sadist, a man whose feelings of possessive love for his daughter veer dangerously and desperately out of control? Or is it the tale of a life coming undone, the sad inevitability of a deprived child grown up to cold manhood and thankless, pointless prosperity - the story of a victim of poverty, circumstance and fate? And anyway, is Julius Levy the master of his own fate (and those around him) or is he in fact no more than face and bluster, no more in control than any of those people he destroys to get what he wants?

Julius

a straightforward account of a monstrous sadist, a man whose feelings of possessive love for his daughter veer dangerously and desperately out of control? Or is it the tale of a life coming undone, the sad inevitability of a deprived child grown up to cold manhood and thankless, pointless prosperity - the story of a victim of poverty, circumstance and fate? And anyway, is Julius Levy the master of his own fate (and those around him) or is he in fact no more than face and bluster, no more in control than any of those people he destroys to get what he wants?

And, maybe most intriguingly of all, what exactly was in du Maurier’s mind when she chose to make him a Jew? A young twenty-something woman scribbling away at her desk in windy Cornwall in 1932 was still safely innocent of the hideous drama to be played out only a few years later in Europe, but the choice can only set our post-Holocaust teeth on edge.‘Jew,’ sneers Julius’s Catholic grandfather to his hapless son-in-law, ‘nothing but a miserable Jew.’

Even though the grandfather is portrayed far from sympathetically - at best a bestial, overbearing peasant - still there were mutterings, in du Maurier’s later years, that this possible whiff of anti-Semitism should be excised from the novel. Apparently du Maurier even took them seriously. But thank goodness she never succumbed. Not only would it have meant bowdlerising a novel that is absolutely and innocently (in the best sense of the word) of its time, but there’s a more important point. Rereading it in the twenty-first century, it seems to me that it’s precisely Julius’s Jewishness - and other people’s attitudes to it - that redeems him, that makes him real and whole and fascinating. It’s his rediscovery of his religion, as he wanders into a temple by chance, that gives him his few moments of calm and happiness. He is not at odds with the world because of his Jewishness but in spite of it.

In fact, far from being a one-dimensional baddie, this spirituality and longing to belong makes du Maurier’s eponymous anti-hero so much grander: a questing, complex and, in many ways, touching man. Without this extra dimension, the novel would be far lighter and more brittle. As it is, it’s a tragedy - a vivid and profound exploration of what it feels to be an outsider, accepted as neither Christian nor Jew, neither aristocrat nor millionaire.

Julius begins and ends the novel with his hands stretched out to the sky, reaching for the clouds, searching, always searching. A mixed-up, lonely, starving child, he responds instinctively to the music in the temple, feels something warm take hold of his heart, realises he is among ‘his own people’. It is Julius’s particular tragedy that he spends the rest of the novel struggling to re-attain this fleeting emotion. If Julius has a benign side, a sensitive side, there’s no doubt that it’s the Jewish side.

Interestingly, du Maurier always avoids the easy racist cliché. Though Julius amasses incalculable wealth, she never portrays him as a money-grabber. He is no blinkered and greedy lover of cash and property - just a man who simply can’t help but work hard and do things well. His abiding code is ‘something for nothing’ but actually, it’s rarely for ‘nothing’ - Julius works and works and works, forgetting even to spend his money.When a friend persuades him to match his lodgings to his newly acquired wealth, it’s significant that Julius is uncomfortable. He’s ‘disturbed’ by his ‘first experience of luxury’. Julius is an ascetic, he’s pure in his soul. He works out of a sense of personal pride and for mental satisfaction, for the chance to take control of his life, rather than the chance to shirk it.

But though Julius will always survive he has, in the best tradition of tragedy, a single undoing flaw. He can’t love without wanting to possess and control. And if he can’t possess then he’d rather destroy - and he’s quite prepared to. As a young boy, forced to leave home and his beloved cat behind, he ties a stone around her neck and flings her in the Seine rather than leave her to an uncertain fate, or worse - to be cared for by someone else.

This act - an act of love in his eyes - is carried out unflinchingly, but it’s the start of a lifelong and sinister equating of love with destruction. When Julius discovers his mother committing adultery and tells his father, it seems painfully logical to him that his father should throttle her there and then. He knows he’ll miss his mother, but didn’t she deserve it, and won’t his father ultimately feel better if no one else can have her? Julius’s reaction to this crime quickly becomes its most disturbing aspect. Here is a boy with an almost autistic lack of sensibility. Where he should connect with others, there is an icy vacuum. He knows he ought to feel something, but he wonders what it should be.

But it’s precisely this vacuum that gives Julius his resilience and power. That’s what lies at the heart of this novel - a study of power and powerlessness, which has little or nothing to do with Jewishness.The helplessness that this young boy feels as a starving child in turn-of-the-century Paris turns him into a sadistic character - someone who discovers ‘a new thing, of hurting people he liked’. This destructive pattern - which ultimately bores him because it means he is always in control and life contains no surprises - continues until he finally meets his match.

His nemesis is his daughter Gabriel, his own flesh and blood, his alter-ego. At last Julius can take pleasure from the existence of another human being - even though the pleasure he feels is obsessive, a ‘voracious passion’ that gives him a ‘sensation in mind and body’ that is ‘shameful and unclean’. It is said that the character of Julius is based heavily on du Maurier’s own father, Gerald du Maurier, and the fact she was able to write it - such steady, concise prose - means she had come to terms with that intensely passionate relationship. It’s an idea I find comforting if baffling. Such candour and control? The author must have been an admirably sorted-out twenty-six year old.

I said at the beginning of this piece that I was far too young when I first read the novel to mine its deeper, darker meanings. Well, not quite. It’s true that I knew nothing of men and women, class, war and money. But I did know a little more than I’d have liked about the uneasy relations of fathers and daughters. The summer before, my mother had left my father and he - furious and unscrupulous - had begun a slow campaign to hurt me, to make me feel his pain. Fuelled by his own sense of powerlessness, it was his way of getting back; of punishing my mother for leaving, of punishing me, at almost fourteen, for looking and sounding more and more like her. I became increasingly afraid of my father - not so much of any single thing he did, more that I realised I did not know his limits. I did not know where he would stop.

Other books

Flambé in Armagnac by Jean-Pierre Alaux, Noël Balen

B00CGOH3US EBOK by Dillon, Lori

Smolder: Trojans MC by Kara Parker

Web of Love by Mary Balogh

Wexford 18 - Harm Done by Ruth Rendell

The Dragon in the Ghetto Caper by E.L. Konigsburg

Journey Between Worlds by Sylvia Engdahl

Behind The Mirror ( The Glass Wall Series - Prelude to Book 1 ) by Adler, Madison, Caine, Carmen

Werewolf Nights (The Pack Trilogy Book 2) by Chanel Smith

Midsummer Eve at Rookery End by Elizabeth Hanbury