Just Fine

JUST FINE

Also by France Daigle

1953: Chronicle of a Birth Foretold

Real Life

France Daigle

Just Fine

A novel

Translated by Robert Majzels

Copyright © 1998 Les Ãditions d'Acadie

English translation copyright © 1999 House of Anansi Press Ltd.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Distribution of this electronic edition via the Internet or any other means without the permission of the publisher is illegal. Please do not participate in electronic piracy of copyrighted material; purchase only authorized electronic editions. We appreciate your support of the author's rights.

This edition published in 1999 by House of Anansi Press Inc.

110 Spadina Avenue, Suite 801

Toronto, ON, M5V 2K4

Tel. 416-363-4343 Fax 416-363-1017

www.houseofanansi.com

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Daigle, France

[Pas pire. English]

Just fine

Translation of: Pas pire.

ISBN 978-1-77089-150-0

1. Title

PS8557.A423P3713 C843'.54 C99-931349-5

PQ3919.2.D225P3713 1999-06-08

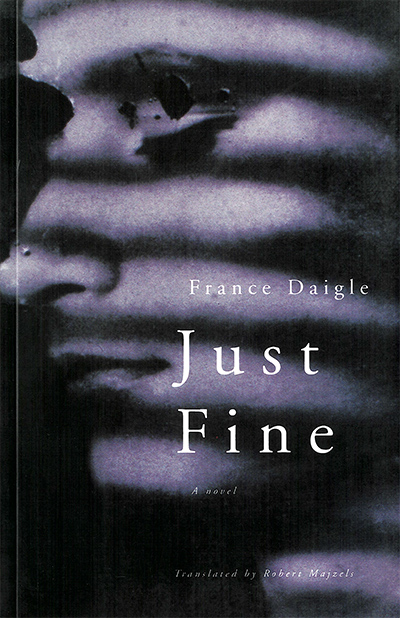

Cover photograph: SPL/Photonica

Cover Design: Angel Guerra

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario

A

rts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). This book was made possible in part through the Canada Council's Translation

G

rants Program.

The author thanks the Canada Council for the Arts for its support of the writing of this book.

JUST FINE

1

Tale of a Step Dance

I

W

INDY SUMMER IN

D

IEPPE

.

The sky is a solid white, that opaque white that, in winter, precedes a snowfall. But we're in summer, in mid-July, and the trees are covered in leaves, shaken and twisted by a wind that comes from everywhere at once, from high in the sky and from the ground, from the fields and from the city, from both ends of Acadia Avenue. This gusting wind has been blowing for days now, shuffling everything â not just the cards, but the rules of the game â to the point where we forget we're in summer, in Dieppe. Dozens of times I've recalled that summer when I separated myself from those who sit quietly at the dinner table.

I'm talking, of course, of Dieppe before the annexation of Saint-Anselme, and maybe even of Dieppe before Lakeburn. I'm talking of the old Dieppe, of central Dieppe, of the Sainte-Thérèse parish, with its Sainte-Thérèse Church beside Sainte-Thérèse School on Sainte-Thérèse Street. I'm talking about the Dieppe surrounded by fields and marshes that we burned every spring, fields of long grass through which slithered a few snakes and a river, the Petitcodiac, which seemed to cut right through our yards. Between our houses and the river, there were more or less overgrown fields. Close to the houses there were lawns and yards where we played games with firmly established rules. Beyond the vegetable gardens and raspberry bushes and a few apple trees there was the true country, marshland covered in long grass, territory of invented games, games we mostly made up in the course of an afternoon, games full of dense grass that moaned when our pants and boots brushed against it.

*

Perhaps reflecting something of the nature and spirit of the scientists who study and describe them, deltas have some profoundly human characteristics: they start out in an embryonic state, emerge, and become rooted. When we chart the six ways deltas generally extend into the sea, the forms we call mouths do indeed resemble the shape of the human mouth. Young deltas are swaddled and flabby; eventually they lie down and thicken with age. Some have lobes, a forehead, arms, a hand, or fingers. We attribute ways of life to them; they experience breakups and accidents. If angered, some will go so far as to kill. Others quietly change beds, subdivide, or reproduce as subdeltas that, like children, are the offspring of the resources and power that formed them. Still others change paths according to circumstances, go over the top, take shortcuts, rid themselves of excess members. Deltas like to play: they love sand and slides and never tire of splashing about in ponds and basins. They race between their banks, sowing reeds and mangroves, sculpting flitches, and uncovering bogs. Since deltas are often more wide than deep, their meanders, swamps, and marshes regularly flood and overflow. Some overflows playfully open up additional beds each spring, setting off new processes, reversing the traditional exchange between fresh- and salt water, heedlessly disregarding the inextricable interpenetration of earth and water, and mischievously covering the world with a new layer of ambiguity.

*

Madame Doucet, a very old woman in the neighbourhood, always had something for us when we brought her flowers. Our bouquets ranged from a lowly clump of dandelions plucked with little effort at her doorstep to more thoughtful arrangements of wild flowers that were, in those days, nameless. In exchange for whatever we had gathered that day, we invariably received a caramel, a slice of apple, a gingersnap, or a biscuit. It was a welcome snack near morning's end or in the afternoon when time dragged and there was nothing else to do. Even the boys occasionally indulged in this covert begging. We showed up at Madame Doucet's several times a week with our bouquets; that she never turned them down caused us to reflect on human nature, for we knew very well that our own mothers would never have played along. In the end, Madame Doucet's limitless patience and kindness so troubled our conscience that sooner or later, any self-respecting child quit the game of his or her own free will.

*

Not every river is blessed with a delta. The fact that the Amazon and the Congo, the two biggest rivers in the world, don't have one proves that a delta requires very particular conditions. Indeed, coastal research by experts has revealed a host of nuances in these conditions. Scientists have distinguished simple deltas from complex deltas, bird's-foot deltas from bell-shaped and atrophied deltas. Their work also describes spring tides and neap tides, terrigenous sediments and flocculation, creeping soil and silting, turbid pluming, lagoons and mudflats, ravines and hummocks. These specialists have studied the age of deltas and have observed that the morphological evolution of many of them is comparable to that of a human lifetime. The differences among deltas, which depend upon weather conditions, the role of wind and vegetation, and the profound perturbations caused by human intervention, have been studied and the various stages in the fall of a river have been mapped. Shifts in riverbeds have also been recorded: the Huang He River, for example, has apparently changed its course and mouth twenty-six times in

3,000

years.

*

Not all children were obliged to be so inventive in order to satisfy their minor personal needs. In some houses, nickels for buying candies were doled out liberally. In others, there were candies in the candy dish all week long. In still others, when you expressed a need, you generally received some kind of response. But there were also houses where there was nothing to be done, where needs were never even expressed. Or those that were expressed were of a completely different nature. When visiting our friends, we slipped into the daily routine of their homes in the same way we got on a merry-go-round, trusting in the particular machinery of the place. Things happened in other kids' homes that were unthinkable in our own, sometimes for the better, sometimes for the worse. All this nourished our gaze. We picked up bits here and pieces there and gathered them together to invent a life. Our lives were composed of these things. Of useful things and useless things. Of things of certain value and things of no apparent value. Of things whose value remained to be discovered.

*

A delta generally forms when the sea fails to redistribute over a wide area the sediment and particles transported by a large river. This transported material is gradually deposited at the mouth of the river, eventually creating small islands or accumulations that impede the water's free flow. To attain the sea, the river breaks up into several smaller rivers, the main branches of which appear to form the sides of an isosceles triangle when seen from the air. Hence the name

delta,

the fourth letter of the Greek alphabet, whose uppercase,

â

, has just such a triangular shape. The visible deltas, or those that present a relatively complex interpenetration of land and water, are the best known. But there are also subaqueous and tidal deltas, which are actually deltas in the process of forming and not considered true deltas. The only criterion for a delta relates to the incursion of land into sea. This incursion can be considerable:

30

kilometres in the case of the Danube, for example, and

140

kilometres in that of the Mississippi delta, which was long considered the biggest in the world. This honour now belongs to the Ganges-Brahmaputra delta. Even the multiplicity of branches is not a criterion for being a delta, although most deltas have many.

II

I

T IS NEITHER FREE nor easy to be born. Buddhists say that it is more difficult for a human to be born than for a blind turtle wandering the depths of an ocean as vast as the universe to stick its head through a wooden ring floating on the water's surface. The turtle's feat is all the more unlikely because the ring is cast about by waves and the turtle rises to the surface only once every one hundred years.

Astrology, on the other hand, claims that every birth corresponds to a cosmic goal of the universe. This means that individuals who are born, or who enter into density, are the fruit of a will and a project, a double project really: perfecting themselves and serving the needs of the universe by contributing their unique abilities. The hour, day, year, and place of a person's birth determine the forces in play at that moment and throughout that life.

Astrology is a highly complex science. Some of its treatises are like prayers while others are poetry. Still others consist of extravagant mathematical tables and vectors. The purpose of these things is to show us that life has meaning and that each of us has a mission, a unique path to follow. Astrology aspires to help people find their way so that they might fulfill their potential. One can ingest this information in small morning doses with one's breakfast or, from time to time, in direct consultation with a professional astrologer. The important thing is not to take astrology too seriously. It can work even if you take it with a grain of salt.

*

In our case, the difficulty lay not so much in being born as in being born to something. Our first efforts toward that end were made at Acadia Elementary School, a grey, entirely square, two-story building across the street from the church. This was a school for grades one, two, and three. We began our apprenticeship under the watchful gaze of two Madame Cormiers, Madame LeBlanc, Mademoiselle Melanson, Mademoiselle Cyr, and Madame Dawson. At first, I put too many humps in my

m

s and

n

s. The teacher finally lost patience with me, which made me cry.

I'm talking about the Dieppe of my school friends Cyrilla LeBlanc, Gertrude Babin, Debbie Surette, Louise Duguay, Charline Léger, Gisèle Sonier, Alice Richard, Lucille Bourque, Thérèse Léger, and Florine Vautour; and the Dieppe of the older guys who hung out at the corner and had names like Titi, Tillote, Pouteau, Pep, Hum, Youma, Lope, Dunderhead, Hawkeye, and Blind Benny.

*

Astrological signs are one thing, the houses of the governing stars are quite another. Each of the twelve astrological houses represents one of the major areas of human activity. In the progression from one house to another, an individual's abilities and aspirations evolve; from one to another, the physical and psychic body grows. The twelve houses, named for the place they occupy on the chart, represent a series of evolutionary stages. They deal with every aspect of an individual's development, from birth to death and beyond. As a whole, they constitute one of the five great components of the science of astrology. The other components deal with the actual signs of the zodiac, the planets, their aspects, and their transitions.

The chart of astrological houses looks like a pie with twelve slices. The first six houses are located beneath the horizontal axis and deal with the individual's growth in the material world, the material organization of life. Houses seven to twelve are found above the horizontal axis and deal with the development of consciousness. Each house relates in a particular way to its opposite house, so that we cannot study the forces in play in one without taking into account those in play in its opposite. Hence, the first house is associated with the seventh house, the second house with the eighth house, and so on. Each house also corresponds to the spirit of a sign in the zodiac. An individual whose heavenly chart shows a planetary concentration in a particular house will present characteristics corresponding to the sign associated with that house and to the sign associated with the time of that person's birth.

*

The firehouse siren wailed at nine o'clock every evening to remind children that it was time to go home. It also wailed when there was a fire. One day the nine o'clock siren did not sound. A part of our world disappeared. Later someone put up a wooden structure containing something that looked like a belfry on the roof of the little Acadia School. We wondered if the addition was intended to replace the siren. We were told it was an alarm in case of war. I seem to remember the word nuclear. It was also suggested that we dig bomb shelters in our basements and store provisions down there, just in case. I mentally began to organize such a shelter in our basement, beside the shelves where we stored jams and a few canned goods.

*

Some of us passed Régis's store and the Palm Lunch restaurant on our way to school every day. The building that housed both these businesses and the barbershop was called the corner, because it was located at the cross-roads of Dieppe's two main arteries, Acadia Avenue and Champlain Street. What made these streets main was probably that they led somewhere other than our friends' houses or the fields. Acadia Avenue led to Memramcook, Champlain Street to the airport.

Régis's was a grocery store with a butcher who sold meat, rounds of cheese, and headcheese. You could buy on credit there. We called it “marking it down.” Régis brought out his notebook and marked down what we bought. Sometimes we paid on the spot. The store also offered a pretty fine selection of penny candies. All the other sweets â chips, sodas, chocolate bars, ice cream â cost five or ten cents. The Palm Lunch also had a candy counter. Often we took the time to compare the two displays before buying, hence the constant coming and going of children between both stores.

The Palm Lunch, whose name we rattled off without a clue as to its meaning, consisted of a long, slightly raised counter lined with spinning stools along one side and cupboards full of the sort of merchandise you'd find in any general store along the other side, next to the candy counter. The owner, Moody Shaban, would often cross from one side to the other to serve us himself. The pinball machines and the billiard table at the back of the restaurant made the Palm Lunch an ideal place to kill time. As it turned out, there were a lot of folks, especially guys older than us, with plenty of time to kill. There was also this one family that was very different from other families, if only because the parents and children often ate at the restaurant, sometimes individually, sometimes together, and sometimes at all hours. I envied them this free diet of hamburgers, hot dogs, french fries, and hot chicken sandwiches, but I wasn't too sure about the mother's dyed, teased hair. Because the palm of a hand was the only definition I knew for the English word palm, I thought the name of the restaurant referred to its fare, most of which you ate with your hands. It was only years later that I realized that the little green-and-red neon palm tree hanging in the window was more than a decoration. It was only years later that the reality, or the unreality, of that palm tree really sank in for me.

Another small store, the Nightingale, was located below the church, that is, at the bottom of the hill, beyond the church. Many of the kids at school lived down there on Orleans, Thibodeau, Gaspe, or Charles streets, to name a few. The people living on Gould Street practically had a variety store, Gould's, to themselves. Candies varied from one shop to another and when new stuff appeared in one store and not the others, it would spark jealousy among the children. The Nightingale became far more mysterious in my eyes when a teacher told us a nightingale was a bird.

*

Once a year, my mother had us make our own root beer. We were always happy to comply and, besides, the homemade brew was good for the family budget since it was cheaper than store-bought pop. We began by pouring a large amount of some liquid concoction into enormous cauldrons to simmer on the stove; then we bottled it all in tall beer bottles. The project was somewhat ambitious. We could never quite believe that so much root beer could come from such a small flask of extract purchased at the pharmacy. Once the bottles were filled, capped, and clean and smooth, we carried them, two at a time, one in each hand, up to the attic. There were probably three or four of us going back and forth to bring the root beer upstairs, where it was left to ripen until we brought it out on special occasions, such as Christmas, birthdays, the occasional Sunday, and, if there was any left, on summer days, when we went for picnics at Belliveau's Beach, our big plaid beach bag stuffed with towels and our willow basket containing a snack. I can still see the green, almost black, bottles wrapped in newspaper and lying one on top of another in the darkness of the attic. Here, already, was a work of art of sorts.