Kate Berridge (13 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Hollow stomachs were never a problem for the other two Estatesâin reverse order of power, the clergy and the nobility. These upper echelons, comprising less than half a million people, owned two-thirds of the land, compared to a tenant class of twenty-five or so million common people. Engravings depicting the plight of the disenfranchised masses used a common imagery of oppression. Typically a peasant was shown giving an uncomfortable double piggyback to a fat noble and a cleric, or, more dramatically, he was being trampled underfoot by them. Men of letters reinforced this theme with grim metaphors. For Abbé Sieyès the nobility and clergy were to the Third Estate âa malignant disease which preys upon and tortures the body of a sick man'. For the historian Sébastien de Chamfort, the Third Estate were the hare, the nobles and clergy were the hounds, and the King

was the hunter. With a hunting-mad king on the throne, this was particularly apt.

Occupying an expansive space between the fat cats of the old order and the teeth-chattering classes too poor to buy firewood were the rapidly growing ranks of the middle class, who were also part of the Third Estate. These employers and entrepreneurs, of whom Curtius is a prime example, enjoyed the fruits of self-made prosperity. They sent their offspring to expensive private schools, and acquired second homes, which they furnished in expensive imitations of aristocratic grandeur. Mercier marvelled at the middle-class makeoversâbell wires installed in walls for summoning servants, expensive carpets, gilt moulding and superb beds. He wrote, âThe middle classes are better housed today than monarchs were two hundred years ago. I believe an inventory of furniture would greatly astonish our ancestors were they to return to this world.' It is this group in particular who followed with avidity the twists and turns of the political drama that unfolded at Versailles between May and June, and which culminated in the Tennis Court Oath, when the representatives of the Third Estate declared themselves a National Assembly committed to working towards the establishing of a constitutional monarchy and the reducing of

Ancien Régime

privileges. There was mounting concern about the mixed messages from the King who, while seemingly compliant with the pushes for reform, was at the same time sanctioning a greatly increased military presence in Paris. French guards and foreign regiments were mobilized in and around the city.

To keep abreast of these developments, the best place to go was the Palais-Royal, which had become the headquarters of Third Estate propaganda. Here Pierre Choderlos de Laclos was one of the writers employed by the Duc d'Orléans to churn out politically inflammatory tracts. In 1783 his epistolary novel

Les Liaisons dangereuses

had scandalized high society and provoked waves of gossip as people speculated on the real-life identity of the amoral protagonists, and his subversive writings stirred up weighty debates. From noon until night beer flowed at the Café Flammande and brandy at the Café Foy, but it was the intake of news and views that was intoxicating. In a letter to his wife the Marquis de Ferrières, visiting from the provinces, evoked the exhilarating atmosphere:

You really can have no idea of the variety of people who regularly collect at the Palais-Royal. The sight is truly amazingâ¦Here a man drafts a reform of the constitution, there a man reads aloud his own pamphlet; at another table someone is castigating a minister; everyone is busy talking each with his own attentive audience. I was there almost ten hours. The paths are swarming with girls and young men. The bookshops are packed with people browsing through books and pamphlets, and not buying anything. In the cafés one is half suffocated by the press of people.

Up until now the most famous orator in the Palais-Royal was a chestnut-seller. On her way to and from the exhibition, Marie would have seen this distinctive figure enthroned on his ebony seat, from where he delivered his legendary sales spiel: âSirs, I have gathered to tell you that I have perfected my talent. I may not be the equal in eloquence of all those who occupy the

lycée

, the museums, the clubs of the Palais, but I am as zealous. They stir up the air with vain words; I prove realities. They caress the ear, I delight the

palais

[palate] by means of an exquisite fruit.' But now soapbox speakers drowned out the âSupérieur des Marronistes'(Chestnut Supremo) with their impassioned appeals to the public to try new political ideas. From every quarterâballad singers, salesmen, pamphleteersâthere was a deluge of words.

With public interest in the political affairs of the day at fever pitch, and the woes of the nation a subject of fierce debate, people flocked to the Palais-Royal, where anti-Establishment rhetoric poured forth. The unbridled ranting amazed Arthur Young; âThe press teems with the most levelling and seditious principles that if put in execution would overturn the monarchy, nothing in reply appears, and not the least step is taken by the court to restrain this extreme licentiousness of publication.' Formerly the Palais-Royal had been a recreational destination, a sensation-seeker's paradise, and time-killer's dream; now it was the natural habitat of a new species of wild-eyed, vein-throbbing fanatic. It was the unofficial news agency, and at any one time the number of people congregating there for the latest updates could be counted in thousands. Arthur Young conjures up a vivid picture:

The coffee houses of the Palais-Royal present yet more singular and astonishing spectacles; they are not only crowded within, but other

expectant crowds are at the doors and windows listening

à gorge déployée

[open-mouthed] to certain orators. The eagerness with which they are heard and the thunder of applause they receive for every sentiment of more than common hardiness or violence against the present government cannot be easily imagined.

Given this edgy atmosphere, it is not surprising that Curtius had decided to remove himself from the crucible of fanaticism. He was not merely an interested observer in the Third Estate cause: his keen interest extended to socializing with many of those involved, and, according to Marie, he was regularly a host to most of the key players who were committed to reshaping the political landscape of France. In her memoirs she describes the new cast of characters at the family dinner table: âFormerly, philosophers and the amateurs and professors of literature, the arts and sciences ever resorted to the hospitable dwelling of M. Curtius. But they were replaced by fanatic politicians, furious demagogues and wild theorists, for ever thundering forth their anathemas against monarchy, haranguing on the different forms of government, and propounding their extravagant ideas on republicanism.' There is a symbolic contrast between the animated scenes at the wooden dining table upstairs and the sedate tableau immediately below, where the wax figures of Louis and Marie Antoinette were still seated in all their formality at the Grand Couvert, fragile figures oblivious of the growing contempt in which they were held.

Talk eventually tipped into action, and from taking passive interest in the issues of the day the people of Paris started to show their readiness to take a participatory role. The symbolic destruction of primitive effigies of those who had incurred the wrath of the people was an ominous indicator of the potential for violence. In succession, two finance ministers who had failed to implement vital reforms were murdered by proxy: in 1787 a primitive effigy of Calonne was hung, and in 1788 a makeshift Loménie de Brienne was ceremonially burned. More menacing, on account of the scale and force of the associated riots, was the mock murder of the wallpaper manufacturer Réveillon in April 1789. A casual remark by this prosperous man about worker's wages was misinterpreted and blown out of proportion to the extent that it incited an angry mob to go on the rampage. They destroyed the printing machines and stock in his

warehouses, and then moved on to ransack the luxurious Rue Saint-Antoine home of this employer who had only ever had the interests of his employees at heart. The rioters had carried a mock gallows through the streets together with a crude dummy of their foe, inviting those en route to come and witness it being hanged and burned in the Place de Grève. Little could Marie have known that this atavistic energy was but the ominous beginning of violent political activism in which the wax heads that were her and Curtius's livelihood would play a major role, where the symbolic and the real would become interchangeable. Wax heads formerly used to celebrate heroes and decry villains, viewed for a small fee by a good-natured public, were imminently to be borne aloft in protest and in triumph, and were then supplanted by real heads on pikes, displayed as bloody trophies of murderous anger.

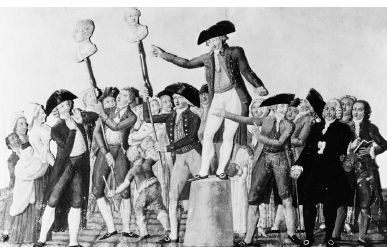

The King's sudden sacking of finance minister Necker on Saturday 11 July was the spark in the powder keg. From now on there was a sense of events overwhelming people, rather than people controlling outcomes. On the afternoon of Sunday 12 July the news of Necker's dismissal reached the Palais-Royal. Inside the coffee shops, along the arcades, to the upper levels of the wealthy residents, and down to the busy bookshops, which these days were permanently packed, this sensational piece of news spread. There were ripples of rumour and panic, and a keenness to know more. As the report of a major happening circulated, many of an estimated six thousand people who were present that afternoon migrated to where the crowd seemed to be concentrating. From a tabletop outside the Café Foy, the charismatic Camille Desmoulins had turned the news into a dazzling speech, a rallying cry to take up arms in protest. While he was in full stride there was a panic that the police were on their way to break up the crowd. He seized on this with a flourish of hyperbole as being âthe sounding of the tocsin of a new St Bartholomew's Massacre'. His already keyed-up listeners were agog, hanging on every word. In the course of his oration he picked a leaf from a nearby tree and urged his stunned listeners to follow suit so that collectively they would be displaying the colour of hope. This improvised insignia was a precursor of the tricolour, which shortly afterwards became the approved emblem of patriotism. To emphasize the seriousness of Necker's loss,

Desmoulins urged the crowd to support the proposal of closing the theatres as a sign of mourning. Seizing on this theme, a contingent of the crowd broke away and made for the theatre district in the Boulevard du Temple, leaving in their wake the sorry sight of a tree stripped of any foliage that was within reach, and the ground strewn with broken twigs.

The first Marie knew of the disturbance was when, after invading the Opéra to demand the immediate suspension of the scheduled performance, the crowd surged noisily along the Boulevard du Temple. Chanting âVive Necker! Vive le Duc D'Orléans', it came to a halt outside the waxworks. Curtius quickly gave instructions for the gates of the railings in front of their house to be shut. But it soon became apparent that the crowd was not as threatening as it looked. Marie describes the protesters as âvery civil and their general bearing so orderly that she felt no alarm whatever'. At the entrance to the exhibition they entreated Curtius to hand over the wax busts of Necker and the Duc d'Orléans, the people's favouritesâthe one whose sacking had strengthened his appeal in their eyes, and the other whose blood-line connection to the King seemed to increase their appreciation of his commitment to their cause. Curtius complied with their requestsânot least because he recognized the makings of a sensational publicity coup. Ever the showman, as he handed over the first bust he declared, âNecker, my friends, is ever in my heart but if he were indeed there I would cut open my breast to give him to you. I have only his likeness. It is yours.' There were bows and bravos all round. The âwhat if' school of historians may be interested in Marie's assertion in her memoirs that the crowd also demanded the figure of the King, âwhich was refused, M. Curtius observing that it was a whole length, and would fall to pieces if carried about; upon which the mob clapped their hands and said, “Bravo Curtius, bravo!” '

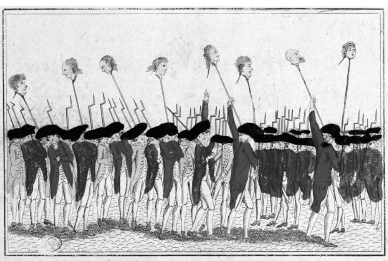

With the heads of their heroes in its hands, the crowd restyled itself as a funeral cortège to show the sorrow caused by the loved minister's fall, and the mood became more sombre. The heads, elevated on shallow pedestals, were draped with black crape, the material of mourning, and to the beat of muffled drums and with black banners edged in white the cortège processed through the streets. An eyewitness, Beffroy de Reigny, was in the Boulevard du Temple at the

time. He put the crowd at âfive or six thousand'. He reports that they were âmarching along, quickly and not in any kind of order', and that they had an improvised selection of weapons and were threatening to burn down any theatres which opened, âsaying that French people should not be enjoying themselves at such a moment of misfortune'.

Wax heads of Necker and the Duc d'Orléans held high to celebrate the people's heroesâ¦