Kate Berridge (28 page)

Authors: Madame Tussaud: A Life in Wax

Tags: #Art, #Artists; Architects; Photographers, #Modern, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

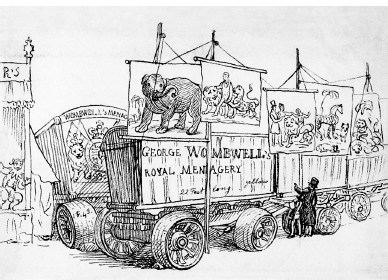

Her travelling years coincided with those of some other famous itinerant showmen, some of whom also built lasting family fortunes. Astley's circus continued to draw huge crowds wherever it went. Of heart-throb status was the stunt rider Andrew Ducrow, who quickened female pulses with his somewhat racy flesh-coloured bodysuit. His fans paid tribute not just with flowers, but also by presenting him with whips, silver spurs and other equestrian tokens of their esteem. Another big name on the same circuit at the same time as Marie was the clown Grimaldi. A large part of his appeal was the way he chronicled the news of the day in a comic format. One of the most successful of her contemporary fellow commercial entertainments was George Wombwell's menagerie. Just as one facet of Marie's appeal was the way she popularized history by proving herself a judicious curator of relics and characters, George Wombwell's menagerie enthralled by making natural history accessible. He boasted that his collection had as great a variety as Noah's ark, and like Marie he maintained a punishing

touring schedule, often overlapping with herâfor example in Bath and Bristol. Records for his returns at Bartholomew Fair show just how popular his menagerie was. In just three days his takings were £1,800, which at sixpence a time means an impressive headcount. Wombwell had the showman's knack of turning adversity into opportunity, and when his elephant died, prompting a rival circus to puff their elephant as âThe Only Living Elephant in England', his immediate response was to print posters offering the public the chance to see âThe Only Dead Elephant in England'.

Wombwell's Menagerie, drawing by George Scharf

It was not only men who made money in show business. Another contemporary of Marie's was Sarah Beffen. She was similarly famous in her own lifetime, and similarly immortalized in the works of Charles Dickensâand in three novels (

Nicholas Nickleby

,

The Old Curiosity Shop

and

Little Dorrit

) compared to Marie's sole mention in

The Old Curiosity Shop

. She was born without arms and legs, yet her dexterity as a miniaturist, a skill she perfected using her mouth and shoulder to control the paintbrush, won her such critical acclaim that she was for many years one of the biggest names on the fairs circuit.

She even won royal recognition, and was granted a pension by George IV, who, mixing bad taste with bon mots, commented, âWe cannot reward this lady for her handy-work, I will not give her alms, but I request she is paid for her industry.'

However, for the very few names who rose to national fame on this circuit, there were vast legions of entertainers who sank without trace. These peripheral people endured lives of real hardship living hand to mouth as they went from one town to the next, following the calendar of fairs, markets and race meetings. They constitute a shadowy underclass. A large number of them were open-air entertainers who moved among the crowds. Not enough pennies in the hat meant sleeping under the stars or in vermin-ridden lodgings where the calibre of patrons was such that the proprietors deemed it prudent to chain cutlery to the dining table. Of this number were the puppeteers, among whom Punch and Judy men were very well represented, the stilt-walkers and the knife-swallowers. There were even people with the skill to regurgitate live rats, who presumably took a crumb of comfort from the fact that if their acts went wrong, they could always restock rodents from their digs.

Marie knew that at any one time she had only the favour of the public between her and a swift descent to the destitution and oblivion that befell so many showpeople. She had no troupe or company to help to dilute disappointments, to give advice and to provide companionship: for many years it was just her and Joseph. But she had ambition, and this, iron will and artistic talent were her assets. She honed various survival strategies on tour, and flexibility about how long she stayed at any one place was key. Her pre-publicity wherever she opened was always carefully orchestrated, but she never committed herself to a set length of time for any specific visit. How long she stayed was always open-ended, and her publicity materials show how she often drummed up numbers by dramatically announcing imminent departure, only to defer it as required. In this way she kept her public hungry for her, and was never humiliated by their dwindling interest. It was a technique that served her well.

As far as we can establish from an early and battered ledger with columns of largely indecipherable entries, she managed to maintain a lifestyle of modest comfort. Her early letters hinted at respectable

lodgings and these seem to have set a level that she maintained. Her assiduous record-keeping, with every penny of outgoings listed alongside takings, suggests that expenditure on presentation was a priority, as one would expect. Outlay on candles was considerable, to create the requisite ambience. Attention to the details of costumes and jewellery was always a source of personal pride, and the ledger hints at this too. She never compromised her high standards, and the wear and tear of touring did not prevent her from exhibiting immaculate figures in freshly laundered outfitsââwasherwoman' and âsoap' are frequently listed in her costs. As for her own dress, austerity and sober respectability disposed her to a matronly style: there were no personal fripperies. A pint of porter, a pinch of snuff, the odd lottery ticket and theatre outing for sureâbut in the main the evidence is of exemplary dedication to the exhibition, and her accounts are a record of frugality and practicality.

Along the way there were music lessons and a smart set of clothes for Joseph, for, much as her own childhood had been an apprenticeship for showmanship, so it was with her son. For a time Marie placed his wax likeness at the door, and encouraged visitors to compare the model to the young man in person. With fluent English (as reported home in early letters) and an engaging personality (again mentioned in letters), he was a good guide and assistant. A peripatetic life meant he had had limited opportunities for a proper schoolroom routine, but, given that they stayed in some places for months at a time, he may have dipped in to the âhedge' schoolsâthe informal, ad-hoc assemblies of juveniles co-ordinated in local communities by philanthropic clergy. We know he learned English very quickly, so he seems to have been a bright little boy, and most probably he was more literate than his mother. By 1814, when they were in Bath, he was even accorded the honour of being introduced as âJ. Tussaud Proprietor' in their publicity, as if at the age of sixteen this was a rite of passage in the life of a budding showman, although his mother, as âMadame Tussaud, Artist', still topped the bill in bigger letters. As he grew up he became more active on the artistic sideâthe music and stagingâand in 1815 he was put in charge of making silhouette portraits of the public, which at one shilling and sixpence proved to be a lucrative and popular sideline.

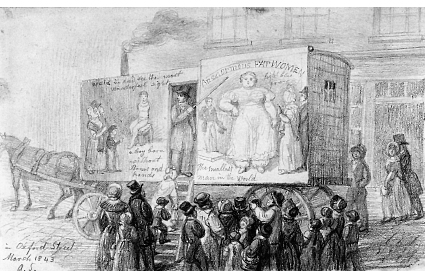

Whatever their individual specialities, and the differences in the size of their shows, the itinerant showfolk specialized in hyperbole, hoax and spectacle. The picture of the bloody-jowled wild beast on the outside of the van often bore no relation to the superannuated mangy creature within. The âBlack Giantesses' announced on posters were often impostors on platform heels with cork-blackened faces; the âPig-faced Ladies' were dogs or bears with shaved faces, draped in poke bonnets and voluminous clothes to complete the disguise. Some acts left spectators completely flummoxed, such as the feats of Chabert, the Fire King, whose seemingly fireproof constitution made him a household name. His star turn took the celebrity chef concept to a whole new level when he made himself the chief ingredient of his recipe for entertainment. In front of packed audiences, he entered a hot oven in which slabs of steak and mutton were simultaneously cooking. The oven had an aperture through which he conversed with the audience, and at the end, to prove the heat that he had endured, he shared the meatâcooked to perfection.

The Times

laconically noted that the joints were devoured with such avidity by the spectators that âhad Monsieur Chabert himself been sufficiently baked, they would have proceeded to a Caribbean banquet'.

Whether on a formal stage or in an informal caravan or booth, the exoticism and escapism on offer elicited a wide range of emotions. There were gasps of wonder, disgust and delight, and occasionally disappointmentâas memorably recorded by one of the spectators of the Living Skeleton. As well known in his day as Chabert, the Living Skeleton did not live up to his reputation as far as Prince Pückler-Muskau was concerned: âThe Living Skeleton was a very ordinary sized man, not much thinner than I. As an excuse for our disappointment, we were assured that when he arrived from France he was a skeleton, but that since he had eaten good English beefsteaks it had been impossible to curb his tendency to corpulence.'

Gradually the rich array of variety acts that had been the back-cloth to Marie's early years on tour started to be overlaid by educational entertainments, as spectacle alone started to be regarded as too frivolous. As audiences became more discriminating, some of Marie's touring companions could not count on the full houses they had once enjoyedâthe man who played his chin could not

really compete with the mechanical genius of Mr Haddock's Androides. âPhilosophical experiments, rational, fashionable and entertaining selections', as one showman described his more cerebral programme. Such learned fare started to eclipse the interest in Siamese twins and learned geese. The days of The Wonderful American Hen were numbered, but, with three wings and four legs, at least the bird billed in her heyday as âThe Greatest Living Curiosity in the World' could make a comeback as the star turn on a dining table. For some fifteen years Signor Capelli's Learned Cats had enchanted audiences by imitating human actionsâroasting coffee, grinding knives and turning a spitâbut now they were damned as being more âindustrious than intellectual'. By the time Marie stops touring there are almost signs of freak fatigue, in favour of educational content. She exemplifies the transition from the traditional innocent fun of the fair to a more elevated style of recreation centred on the town, not the country, and tapping into the new sensibility of aspiration.

Freakshow caravan, drawing by George Scharf

Although she followed the circuit established by the fairs, many of which kept to a seasonal calendar and were often linked to race meetings, livestock auctions or specialized markets, she kept herself well apart from the open-air temporary set-up of the booth and tent. She hired premises attached to public houses, hotels, and theatres, and where they were available she customized many of the comparatively new assembly rooms, which from the late eighteenth century were an innovative civic amenity in provincial towns. Some assembly rooms had separate function rooms, and sometimes Marie was able to maintain her exhibition in one part of the rooms while the ball season was ongoing. On one occasion, in York, she turned this shared-premises arrangement into a public-relations opportunity. When the distinguished guests attending the ball stopped their quadrilles and waltzes to retire for tea, Joseph drew back the canvas screen concealing the space dedicated to their exhibition, and before resuming dancing the guests were able to enjoy the interlude by inspecting the figures. The proceeds of their private view were donated to the Fund for Distressed Manufacturersâa charitable act which was reported in the press, thereby generating a very favourable impression of Madame Tussaud as a woman with a social conscience, an impression that one conjectures was part of her calculated publicity campaign, in which everything she did worked towards creating a very particular impression of herself in the public eye.

Of all the premises where she exhibited, assembly rooms were the perfect milieu for Madame Tussaud. They were a bricks and mortar, or rather gilded-cornice and chandelier-bedecked, manifestation of her ethos. They were the parade grounds of polite society, a forum for elegant recreation. Their value as a venue for social mixing, a place to see and be seen, was captured by Jane Austen. When Mr Darcy makes his entrance in the assembly room at Meryton, the room crackles with âthe report which was in general circulation within five minutes after his entrance, of his having ten thousand a year'. Designed in part for balls, they were equipped to accommodate orchestras, and a high standard of lighting was also a feature. The overarching aim was to create a congenial environment in which to display the dash and dazzle of provincial society at play. These amenities lent themselves particularly well to Marie's personal style of promenade, which she developed in

the 1820s, making music a crucial component of the experience. She cultivated an environment where people-watching was a legitimate part of the pleasure. After a pleasant perambulation around her wax figures, visitors could avail themselves of strategically placed ottomans and chairs and appraise those still inspecting the exhibits. Just as the study of human nature informs her fiction, in life Jane Austen was a compulsive people-watcher, and she testifies to the attraction of exhibitions as a social experience, confessing, âMy preference for men and women always inclines me to pay more attention to the company than the sight.'