Katrina: After the Flood

Read Katrina: After the Flood Online

Authors: Gary Rivlin

Table of Contents

Chapter Three: Behind Enemy Lines

Chapter Four: A First Burst of Optimism

Chapter Five: The Shadow Government

Chapter Eight: He Said, She Said

Chapter Twelve: Shrink the Footprint

Chapter Thirteen: Isle of Denial

Chapter Fourteen: Look and Leave

Chapter Fifteen: A Smaller, Taller City

Chapter Seventeen: Chocolate City

Chapter Eighteen: The Mardi Gras Way of Life

Chapter Nineteen: Darkness Revealed

Chapter Twenty-One: “You'll See Cranes in the Sky”

Chapter Twenty-Two: Eight Feet Across

Chapter Twenty-Four: Vanilla City

Chapter Twenty-Six: The Sore Winner

Chapter Twenty-Seven: Return to Splendor

Chapter Twenty-Eight: “Get Over It”

Katrina: After the Flood

Gary Rivlin

Simon Schuster (2015)

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster eBook.

Sign up for our newsletter and receive special offers, access to bonus content, and info on the latest new releases and other great eBooks from Simon & Schuster.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

or visit us online to sign up at

eBookNews.SimonandSchuster.com

For Daisy

CONTENTS

1: The Banker

2: Air Force One

3: Behind Enemy Lines

4: A First Burst of Optimism

5: The Shadow Government

6: Looking the Part

7: Cassandra

8: He Said, She Said

9: Rita

10: Brick by Brick

11: Blue Sky

12: Shrink the Footprint

13: Isle of Denial

14: Look and Leave

15: A Smaller, Taller City

16: Limbo

17: Chocolate City

18: The Mardi Gras Way of Life

19: Darkness Revealed

20: Road Home

21: “You’ll See Cranes in the Sky”

22: Eight Feet Across

23: Fatigue

24: Vanilla City

25: Blight

26: The Sore Winner

27: Return to Splendor

28: “Get Over It”

They say that in New Orleans is to be found a mixture of all the nations. . . . But in the midst of this confusion what race dominates and gives direction to all the rest?

—

Alexis de Tocqueville,

1832

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Water still covered much of New Orleans the first time I saw the city after Hurricane Katrina. Armed soldiers were stopping cars at roadblocks set up on the perimeter of the metro area. I had hitched a ride with a Republican state senator anxious to get to her flooded home and her then husband. My press credentials got us through one checkpoint; her legislative ID convinced the National Guard to allow us to pass through another. The highway was empty when, once inside the city limits, we hit an elevated stretch of road offering a panoramic view. This was the flooded city the world was seeing on television, but even there on the highway it still seemed unreal, like a special effect ordered up by Steven Spielberg. Eighty percent of the city lay underwater—more than 110,000 homes and another 20,000 businesses.

A week earlier, I had been sitting in the San Francisco bureau of the

New York Times

writing about Google, Facebook, and Silicon Valley’s next crop of underage billionaires. My New Orleans was the New Orleans of tourists: Bourbon Street, Mardi Gras, the Jazz & Heritage Festival, po’ boys. I had no connection to anyone living there. But an all-hands mentality prevailed at the

Times

given a disaster that displaced more than one million people.

My editor asked if I could help out, and a few days later I was picking up car keys at a rental counter at the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport, around an hour north and west of New Orleans. My new office

was whatever patch of free space I could find at a place my colleagues had already dubbed “the plantation”—a white-columned, antebellum house in Baton Rouge normally rented out for parties that the

Times

had transformed into a makeshift newsroom and barracks. We’d take turns in New Orleans, sleeping in a trio of rooms the paper had booked at the Sheraton there, which, as one of the few functioning hotels in the center of town, also served as the city’s main meeting place.

Most everyone around me was looking backward in those earliest weeks after Katrina. Teams of scientists were exploring how and why the levees around New Orleans had failed on the morning of Monday, August 29, 2005, when Katrina struck the Louisiana coast. Medical examiners around the region still had no idea what the final death count might be. There were reports of euthanized patients inside a New Orleans hospital. Three dozen elderly patients had supposedly been left to die at a nursing home. Reporters were assigned to each of those topics, but most were focused on the botched rescue, which had played out live on television. Thousands waited helplessly on elevated sections of the interstate, hungry and thirsty and looking skyward for the help that was not coming. It took the government four days to send the buses needed to rescue the twenty-five thousand people stranded inside the Superdome. Another twenty-four hours passed before buses were dispatched to pick up people at the Ernest N. Morial Convention Center, where another twenty thousand had taken refuge. The most powerful nation on earth had failed its citizens so miserably. Blame needed to be assigned.

Yet even before getting on that plane to Baton Rouge, my instincts had me looking forward to the mess ahead. Eventually, the floodwaters would recede. How would New Orleans go about the complicated task of rebuilding? The majority of the city’s police and fire stations had flooded. So, too, had most of the city’s schools. Flooding had destroyed the city’s electrical system and disabled its sewer and water systems. Even the weight of all that water on the streets proved catastrophic, cracking gas lines and underground pipes and, in some cases, the roadways themselves. Most of the city’s buses had been destroyed along with dozens of its streetcars. Meanwhile, powerful voices in Washington were saying the city shouldn’t be rebuilt—that a low-lying delta was no place for a city (except if there wasn’t a New Orleans at the mouth of the

Mississippi to serve as a port of entry to the thirty-one states and two Canadian provinces that are part of the Mississippi River Valley, they’d have to build a city there given its geographic significance).

The storm meant New Orleans would be without most of its revenues. All those shuttered businesses represented millions in lost sales tax revenues each month. Collecting property taxes, the city’s second-largest source of revenue, seemed unrealistic in a city 80 percent underwater. Five weeks after the storm, the city laid off nearly half its workforce, including most of its Planning Department. New Orleans had long been one of the country’s poorest and most violent cities. The Orleans Parish schools had been through eight superintendents in seven years, and off and on the New Orleans Police Department (NOPD) had been among the country’s most notorious. And racial tensions were never far from the surface in New Orleans. “Our celebratory culture and accepting nature conceals a city with a troubled soul,” Silas Lee, a well-liked black commentator, had written two years before Katrina. For two decades, Lee, a pollster with a PhD in urban policy, had been studying the socioeconomic makeup of the city. During that time, the portion of black New Orleanians earning a high school or college degree had dramatically increased, yet the income gap between black and white had widened. “Behind the mask,” Lee wrote, “resides a divided city.”

My temporary posting became more permanent when, around one month after Katrina, I was assigned to the “storm team” assembled to handle the paper’s coverage of Katrina. My center of gravity shifted from the plantation to the Sheraton in New Orleans, where my neighbors included the president of the City Council and other elected officials who had lost their homes in Katrina. New Orleans then felt more small town than big city—home to maybe twenty thousand people where it wasn’t uncommon to run into the mayor several times a week.

Any journalism endeavor has an element of luck. I wasn’t in Baton Rouge twelve hours when I sat across the desk from Louisiana lieutenant governor Mitch Landrieu, who would play a central role in the story I tell here. That night, I racked up a bar bill of nearly $200 at a restaurant popular among political insiders, collecting names and cell phone numbers—the only digits that would count for months in a city of shuttered businesses and flooded homes. That’s how I was able to reach the

personal friend of George W. Bush who served as Karl Rove’s eyes and ears in New Orleans and also Alden McDonald, a savvy, well-connected black banker whom the mayor would invite to shape the rebuilding plan as a member of the Bring New Orleans Back Commission.

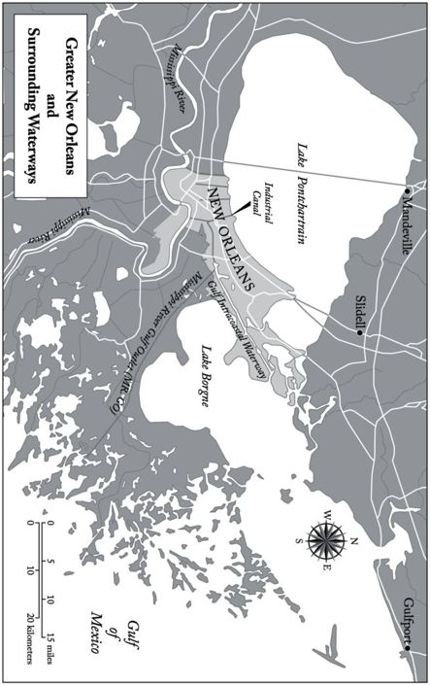

“Bring a map of New Orleans” was McDonald’s only precondition when he agreed to meet with me eleven days after Katrina. The talk then was of an equal-opportunity storm that had hit black and white alike, but he was having none of it. Sitting in the makeshift office his people had set up for him in the back of a bank branch in Baton Rouge, he drew a line down the middle of the map. He pointed to the western half of New Orleans. That’s the New Orleans you know, he said: the French Quarter, the Superdome, the Warehouse District, the Garden District, St. Charles Avenue. Then he pointed to the eastern half of the map. That’s where he lived, McDonald said, and also most of his customers. “Where you saw water up to the rooftops?” he said. “That’s where most of the city’s black people lived.”