Kerry Girls (7 page)

Authors: Kay Moloney Caball

By early 1848 some of the ‘orphans’ had been in the Kenmare, Killarney and Listowel workhouses since they opened on 1845. (In Dingle they would have been in the temporary workhouse since it opened there in February 1848.) Some of the girls were undoubtedly genuine orphans in that both parents were dead. Close family relationships then the norm would not have allowed these genuine ‘orphan’ children to be placed in the workhouse unless the family situation was desperate – it would have been a last resort. Others had been there only since the start of the Famine in 1846 or later and would have been a mix of those who had gone into the workhouse with the entire family or those who had one parent alive and who put a daughter in the workhouse to guarantee at least two meals a day and shelter.

A memory that has remained strong in Kerry folklore is the horror of the poorhouse. In the 1960s a teacher’s threat to a reluctant student usually included a reference to ‘ending up in the workhouse’ if more effort was not put into studying. The stigma of having a ‘workhouse’ background remained with those who entered it and served to terrify those who managed to survive these hungry and disease-ridden times.

Catherine Ryan

Catherine Ryan was baptised on 6 June 1830 in Ballylongford Roman Catholic Church with an address as Tarbert, County Kerry. Her parents are listed as Michael Ryan and Margaret Driscoll. Records from Ballylongford Parish Register show that Catherine had two brothers, an older one called Patrick, born in 1829, and a younger one, Thomas, born in 1832.

Viv Melville, Catherine Ryan’s great-great-great-granddaughter, continues:

Tarbert is a small town in the north of County Kerry, on the Shannon estuary. From Baptismal records it would appear that at the time of her birth, the family were living between Tarbert and Ballylongford, eking out a subsistence living on a small plot of rented farmland. In the 1832 Tithe Applotments record there is a Michael Ryan living at Carhoonakilla, Tarbert with 4 acres, 1 rood, 35 perches which would appear to be the Ryan family place. In Griffith’s Valuation, (1848–1864) however, the same land is valued at only £4 5s. 0d. per year and no house is included. There is a house and land also in the name of Michael Ryan nearby, Cockhill townland valued at 11s and the Landlord there is William Sandes.

17

He was a member of the notorious Sandes lineage, but he has been described as ‘the most fair-minded of the Sandes family.

Catherine seems to have lost all her family during the Great Famine and she ended up in Listowel Workhouse.

Catherine was one of the lucky girls who travelled on the

Thomas Arbuthnot

with the humane Surgeon Superintendent Strutt looking after them. After arrival in Sydney and two weeks spent in the depot at Macquarie Street, Catherine had a Memo of Agreement with Henry G. Douglass, who was the physician for the Sydney Infirmary and Benevolent Asylum.

By April 1853, Catherine was in Melbourne, Victoria where she married Irishman Patrick Keays, in St Francis’ RC Church. Patrick had come to Ireland from Queen’s County, on board the ship

Lloyds

accompanied by his younger brother John. Patrick (26) is listed on the passenger register as a ‘ploughman’ and John (23) as a ‘labourer’. They were listed as Roman Catholic and both could read and write. They had initially arrived in Sydney in 1850 but, like many, had been lured south by the gold discoveries in Victoria. On the shipping register Catherine was listed as being able to read and write, and yet she could only sign her marriage certificate in 1853 with an ‘X’. It’s possible she told a few ‘white lies’ to get herself accepted by the Earl Grey Scheme’s commissioners. Letters written by her do survive but they were not written until 1914, suggesting that she learned to read and write in her later years.

After their marriage, Catherine and Patrick settled at Kangaroo Flat in the Bendigo goldfields, where they remained for much of the next twenty years and where Catherine spent most of her time producing a family of eleven children. In 1869, the Victorian government enacted the Free Selection Act in order to encourage the settlement of the mining population onto the farmlands of Victoria. Patrick and Catherine took up the offer in 1874 and applied for a lease of 320 acres at Tongala, 140 miles north of Melbourne, near the Murray River. Patrick was badly injured when logs fell on his legs, breaking one and badly crushing the other. Thinking he would never be able to work the land again, they were forced to give up the lease and returned to Golden Gully in Bendigo.

By 1877 however, Patrick had recovered sufficiently to apply for another land grant and by 1 June 1878, Catherine and Patrick began occupying a Crown Lease of 225 acres in the Parish of Narioka, near the town of Nathalia. This was harsh, dry land, which demanded unceasing efforts and deep reserves of courage and perseverance. Neither Catherine nor Patrick were young at this time – Catherine would have been about 48 and Patrick in his early 50s. Their eldest boys, William, Thomas, Michael and James, had all left home, but the family was still large: Margaret aged 20, Patrick 16, John 14, Joseph 11, Mary 9 and Peter the youngest at 5.

The first priority on acquiring land was shelter for their large family, so a slab hut was built comprising of two rooms with a bark roof. Optimistically they named their property ‘Rosalind Park’ after the beautiful park near their old home in Bendigo, and set about clearing and fencing the land. They gradually added a stable, barn, dairy and piggery and raised wheat, barley, cattle and pigs. But life was tough and Patrick’s name appeared sometimes on the Arrears Lists when droughts, crop failures and loss of equipment and animals made it impossible to keep up with rent payments.

It seems that most of the Keays boys inherited their father’s dream of striking gold. Having grown up on the goldfields, it was probably not surprising that ‘life on the land’ didn’t initially appeal to them. All the boys except Thomas and Peter went seeking their fortunes in the goldfields of Queensland, Victoria, New South Wales or Western Australia. James Keays even ventured to South Africa, where he died in Durban of Madagascar Fever, aged 28. There were newspaper articles at the time, suggesting that James may have been involved with and even had been murdered by a fellow who was a contender for the Jack the Ripper title!

In the July of 1900, Catherine lost her husband of forty-seven years. Patrick was about 75 and died intestate. Catherine was appointed administrator of his estate and took over the running of his property, which at the time of Patrick’s death, was valued at £1,411 5

s

0

d

. The house had been expanded by this time and now consisted of a six-roomed weatherboard house with an iron roof. There was a detached slab kitchen also with an iron roof and several outbuildings including a stable, a blacksmith’s shed and a dairy.

In January 1901, the lease of the property was transferred into Catherine’s name and she became the official owner of Rosalind Park.

Her youngest son Peter was the only one of her boys to remain on the property and he along with Catherine and his sister Margaret ran the property for the next twenty-one years. Peter married Cecelia Brown in 1910 but in 1913 she died giving birth to their daughter Mercia. So Catherine, at the age of 80, became the primary carer for her infant granddaughter. In letters to her son Tom in Melbourne, she spoke about having to use condensed milk because their cow was only giving enough for the baby, and mentioned that ‘Mercia [was] beginning to creep and wants more attention’.

Catherine died at Rosalind Park on 7 August 1921 in her early nineties. She was a true pioneer, a woman of inspirational strength and endurance who had survived the Great Famine, the workhouse, a three-month voyage to an unknown land, twenty years on the goldfields, the births of eleven children and the deaths of three of them, and all the terrors and trials that the farming life in Australia could throw at her.

1

Peter Higginbotham,

The Workhouse in Ireland

, accessed 2 July 2013

http://www.workhouses.org.uk/Ireland/.

2

Ibid.

3

1 & 2 Vic. C.56 An Act for the more effectual relief of the Destitute Poor in Ireland

British Parliamentary Papers

.

4

Poor Law Commissioners, State of the Unions in Ireland,

http://eppi.dippam.ac.uk/documents/12269/eppi_pages/296037

accessed February 2013.

5

Brid A. Liston,

Education in Listowel Workhouse 1845–1859

, Research Project, Education Department, Mary Immaculate College, Limerick, quoted in John Pearse,

Teampall Bán

(Listowel 2014).

6

Noel Kissane,

The Irish Famine

,

A Documentary History

(National Library of Ireland 1995), p. 101.

7

Fr Kieran O’Shea, ‘In the Line of Duty’, in

The Famine in Kerry

, Michael Costelloe (ed.)

(KAHS Tralee 1997), pp. 28–30.

8

Ibid., pp. 56–57.

9

Ibid., p. 57.

10

Sr Philomena McCarthy,

Kenmare and its Storied Glen

(Killarney 1993), p. 66.

11

Diary of Fr John Sullivan, Kerry Diocesan Archives, Killarney.

12

Fr Kieran O’Shea, ‘In the Line of Duty’, in

The Famine in Kerry

, Michael Costelloe (ed.)

(KAHS Tralee 1997), p. 30.

13

William J. Smyth,

‘

The Province of Munster and Great Famine’ in

Atlas of Great Irish Famine

(Cork 2012), p. 369.

14

Ibid.

15

John Pierse,

Teampall Bán

(Listowel 2013).

16

Ibid.

17

Smith’s

History of Kerry

, indicates that Lancelot Sandes was granted an estate in Kerry in 1667 under the Acts of Settlement. The estate of Charles L. Sandes was one of the principal lessors in the parish of Aghavallen, barony of Iraghticonnor, at the time of Griffith’s Valuation.

The Ordnance Survey Name Book

noted in the 1830s that he held lands from the Trinity College estates.William Sandes held several townlands in the parishes of Kilnaughtin, Knockanure and Murher, in the same barony. In 1863,1864 and 1865, over 2,000 acres of William Sandes estate was offered for sale in the Landed Estates Court.

CIRCUMSTANCES IN AUSTRALIA

T

HE

E

ARL

G

REY

Scheme was not the first scheme devised by the colonial authorities in conjunction with the British Government, in order to balance the male surplus then in existence in Australia. In 1831, a number of girls from an orphanage in Cork were sent to New South Wales, paid for by the colonial government. From this time onwards there were offers of free passage available to the colony for women emigrants. These efforts were not very successful, as at that time it was impossible to persuade women of ‘good character’ to travel alone on long sea voyages to an unknown and undeveloped land that had the reputation of being in the main a penal colony. As a result, the majority who travelled were women who had been taken off the streets of the main British cities – London, Liverpool and Dublin. While the authorities wanted and needed women to travel and successfully take up residence in Australia, no effort was made to look after them on the voyage or after their arrival. As a result, with no employment or accommodation arranged, many of these girls became prostitutes. In 1838, 600 homeless girls, the majority of them Irish, were wandering the streets of Sydney and sleeping out at night in the parks or beneath the shelter of rocks in area.

Following the end of convict transportation to Eastern Australia in August 1838, the colonial administrators had to consider how they would fill the labour workforce required to continue the expansion of their developing colony. When looking for male labour, initially consideration was given to recruiting Chinese and Indians; £1,500 had been dispatched to Singapore that year with an ’order’ for 100 such men.

1

This idea did not go very far, as the colonial authorities wanted white Europeans and in particular workers from what was regarded by most as ‘the home country’ – England. Understood, if not stated, was the expectation that these English workers would also espouse the Protestant faith and display a Protestant ethos of hard work and moral rectitude. In 1840, as the shortage of labour became acute, an Immigration Association was formed in South Australia, for the ‘promotion and improvement of Bounty Immigration to this colony’.

2

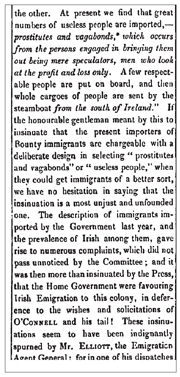

While the aims of the association were admirable, the fact was that there was ‘an urgent and increasing demand for labour’ which was not being met by the Government to their satisfaction, and this was the driving force in the association. They were promoting the Bounty system to ‘import 3550 adults of the best description’, which they estimated would cost £71,000

3

rather than the previous Government system. ‘At present, we find that great numbers of useless people are imported – prostitutes and vagabonds

… a few respectable people are put on board and then whole cargoes of people are sent by the steamboat from the south of Ireland’.

4