Killing Jesus: A History (17 page)

Read Killing Jesus: A History Online

Authors: Bill O'Reilly,Martin Dugard

Tags: #Religion, #History, #General

Before they can reply, Jesus turns to the crowd and says, “Listen to me. Understand this: Nothing outside a man can make him ‘unclean’ by going into him. Rather, it is what comes out of a man that makes him unclean.”

* * *

The Pharisees walk away before Jesus can further undermine their authority. The remaining crowds make it impossible for the disciples to eat in peace, so Jesus leads them into a nearby house to dine without being disturbed.

But the disciples are unsettled. In their year together, they have heard and absorbed so much of what Jesus has said and have been witness to many strange and powerful events they do not understand. They are simple men and do not comprehend why Jesus is so intent on humiliating the all-powerful Pharisees. This escalating religious battle can only end poorly for Jesus.

“Do you know that the Pharisees were offended?” one of them asks Jesus, stating the obvious.

Then Peter speaks up. “Explain the parable to us,” he asks, knowing that Jesus never says anything publicly without a reason. Sometimes the Nazarene’s words are spiritual, sometimes they contain a subtle political message, and sometimes he means to be uplifting. In the past few months, Jesus has debated the Pharisees about everything from eating barley on the Sabbath to hand washing, today’s debate, which seemed pointless to Peter. Perhaps the disciples have overlooked an important subtext to Jesus’s teaching.

“Are you still so dull?” answers an exasperated Jesus.

Jesus continues: “Don’t you see that whatever enters the mouth enters into the stomach and then out of the body. But the things that come out of the mouth come from the heart, and these make a man unclean. For from within, out of men’s hearts come evil thoughts, sexual immorality, theft, murder, adultery, greed, malice, deceit, lewdness, envy, slander, arrogance, and folly. All of these evils come from inside and make a man unclean.”

Judas Iscariot is among those listening to the words of Jesus. He is the lone disciple who was not raised in Galilee, making him a conspicuous outsider in the group. There is no denying this. He wears the same robes and sandals, covers his head to keep off the sun, and carries a walking stick to fend off the wild dogs of Galilee, just like the rest of the disciples. But his accent is of the south, not the north. Every time he opens his mouth to speak, Judas reminds the disciples that he is different.

Now Jesus’s words push Judas further away from the group. For Judas is also a thief. Taking advantage of his role as treasurer, he steals regularly from the disciples’ meager finances.

4

Rather than allow Jesus to be anointed with precious perfumes by his admirers, Judas has insisted that those vials of perfume be sold and the profits placed in the group’s communal moneybag—all so that he might steal the money for his own use. Judas’s acts of thievery have remained a secret, and, like all thieves, he carries the private burden of his sin.

5

Now Jesus is deepening Judas’s shame by reminding him that he is not merely a sinner but also unclean. To be morally unclean in Galilee is not just a spiritual state of mind; it is to enter a different class of people. Such a man becomes an outcast, fit only for backbreaking occupations such as tanning and mining, destined to be landless and poor for all his days.

Judas has seen these people. Many of them fill the crowds that follow Jesus, simply because they have nothing better to do with their time, and Jesus’s words offer them a measure of hope that their lives will somehow improve. They have no families, no farms, and no roof over their heads. Others turn to a life of crime, becoming brigands and highwaymen, banding together and living in caves. Their lives are hard, and they often die young.

This is not the life Judas Iscariot has planned for himself. If Jesus is the Christ, as Judas believes, then he is destined one day to overthrow the Roman occupation and rule Judea. Judas’s role as one of the twelve disciples will ensure him a most coveted and powerful role in the new government when that day comes.

Judas apparently believes in the teachings of Jesus, and he certainly basks in the Nazarene’s reflected celebrity. But his desire for material wealth overrides any spirituality. Judas puts his own needs above those of Jesus and the other disciples.

For a price, Judas Iscariot is capable of doing anything.

* * *

Frustrated by their inability to trap Jesus but also believing they have enough evidence to arrest him, the Pharisees and Sadducees return to Jerusalem to make their report. And while it may seem as if Jesus is unbothered by their attention, the truth is that the pressure is weighing on him enormously. Even before their visit, Jesus hoped to take refuge in a solitary place for a time of reflection and prayer. Now he leaves Galilee, taking the disciples with him. They walk north, into the kingdom ruled by Antipas’s brother Philip, toward the city of Caesarea Philippi. The people there are pagans who worship the god Pan, that deity with the hindquarters and horns of a goat and the torso and face of a man. No one there cares if Jesus says he is the Christ, nor will the authorities question him about Scripture. While Caesarea Philippi is just thirty-four miles north of Capernaum, Jesus might as well be in Rome.

Summer is approaching. The two-day journey follows a well-traveled Roman road on the east side of the Hulah Valley. Jesus and his disciples keep a sharp eye out for the bears and bandits that can do harm, but otherwise their trip is peaceful. Actually, this constitutes a vacation for Jesus and the disciples, and they aren’t too many miles up the road before Jesus feels refreshed enough to stop and relax in the sun.

“Who do the people say I am?” Jesus asks the disciples, perhaps inspired by the great temple at Omrit, dedicated to Caesar Augustus, a man who claimed to be god but who was, in the end, just as mortal as any other man.

“Some say John the Baptist, others say Elijah, and still others Jeremiah or one of the prophets,” comes the reply.

It is often this way when they travel: Jesus teaching on the go or prompting intellectual debate by throwing out a random question. Rarely does he confide in them.

“But what about you?” Jesus inquires. “Who do you say I am?”

Peter speaks up. “You are the Christ, the son of the living God.”

Jesus agrees. “Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for this was not revealed to you by man but by my heavenly father,” he says as he praises the impulsive fisherman, using Peter’s former name. “Don’t tell anyone,” Jesus adds as a reminder that a public revelation will lead to his arrest by the Romans. They may be leaving the power of the Jewish authorities behind for a short while, but Caesarea Philippi is just as Roman as Rome itself.

But if the disciples think that Jesus has shared his deepest secret, they are wrong. “The Son of Man must suffer many things and be rejected by the elders, chief priests, and teachers of the law,” Jesus goes on to explain.

This doesn’t make sense to the disciples. If Jesus is the Christ, then he will one day rule the land. But how can he do so without the backing of the religious authorities?

And if that isn’t confusing enough, Jesus adds another statement, one that will be a source of argument down through the ages.

“He must be killed,” Jesus promises the disciples, speaking of himself as the Son of God, “and on the third day be raised to life.”

The disciples have no idea what this means.

Nor do they know that Jesus of Nazareth has less than a year to live.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

JERUSALEM

OCTOBER, A.D. 29

DAY

Pontius Pilate sits tall as he rides to Jerusalem. His wife, Claudia, travels in a nearby carriage, as Pilate and his escorts lead the caravan through unfriendly terrain. Pilate has three thousand men at his disposal. They are not actual Roman soldiers but the same mix of Arab, Samarian, and Syrian forces who once defended Herod the Great.

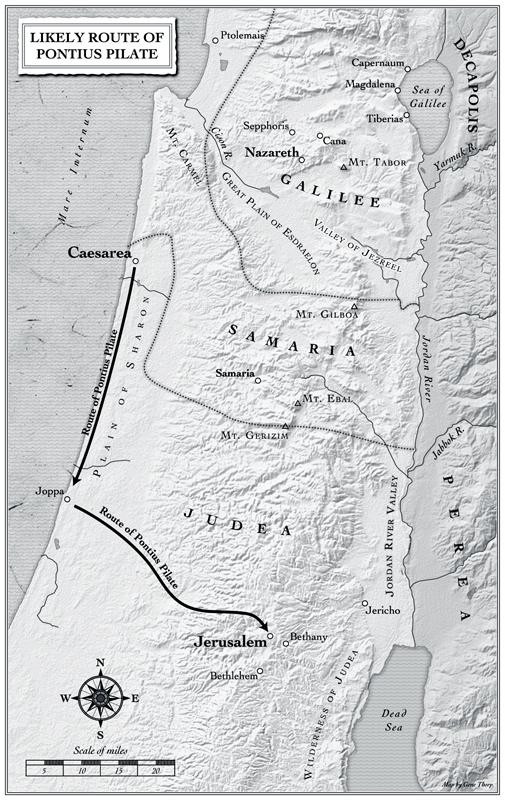

Pilate’s military caravan has set out from the seaside fortress of Caesarea. The Roman governor makes the trip to Jerusalem three times a year for the Jewish festivals.

1

The sixty-mile journey takes them south along the Mediterranean, on a paved Roman road. After an overnight stop, the route turns inward, onto a dirt road across the Plain of Sharon and on up through the mountains to Jerusalem.

Pilate intends to lend a dominant Roman presence to the Feast of Tabernacles,

2

one of three great celebrations on the Jewish religious calendar. Much like Passover, this holiday involves pilgrims by the hundreds of thousands traveling to Jerusalem to celebrate. The Jews commemorate forty years of wandering in the desert and enjoy a feast to celebrate the completion of the bountiful harvest. Pilate has little patience for Jewish ways. Nor does he think the Jews are loyal to Rome. The governor walks a fine line during these festivals: if the Jews revolt—which they are wont to do when they gather in such large numbers—he will take the blame, but if he cracks down too hard, he could be recalled to Rome for disobeying Tiberius’s order that these people be treated as a “sacred trust.”

Thus Pilate endures the festival weeks. He and Claudia lodge themselves in the opulence of Herod the Great’s palace and venture out only when absolutely necessary.

Pontius Pilate has been prefect of Judea for three years. His job as governor should be as simple as mediating local disputes and keeping the peace, but in fact the role of the occupier is always fraught with peril. The Jewish philosopher Philo will one day write that Pilate is “a man of inflexible, stubborn and cruel disposition,” and yet the Jews have already managed to outsmart him and damage his career. On the occasion that Pilate ordered Roman standards to adorn the Temple, not only did the residents of Jerusalem succeed in having them removed, but they also wrote a letter to Emperor Tiberius detailing Pilate’s indiscretion.

Tiberius was furious. As the historian Philo will report, “Immediately, without even waiting for the next day, he wrote to Pilate, reproaching and rebuking him a thousand times for his new-fangled audacity.”

This year, tensions are running even higher, and the finger of blame can be pointed only at Pilate. He had the ingenious idea of building a new aqueduct to bring water to Jerusalem, but he faltered in this act of goodwill by forcing the Temple treasury to pay for it. The Jewish people were outraged about this use of “sacred funds,” and during one recent festival, a small army of Jews rose up to demand that Pilate stop the aqueduct’s construction. They cursed Pilate when he appeared in the streets of Jerusalem, taking courage from the size of the crowd, thinking that their words would be rendered anonymous.

But Pilate anticipated the protest and disguised hundreds of his soldiers in the peasant robes of Jewish pilgrims, with orders that they conceal a dagger or club beneath the folds of their robes. When the crowd marched on the palace to jeer more violently at Pilate, these men surrounded the mob and attacked them, beating and stabbing the unarmed pilgrims. “There were a great number of them slain by this means,” the historian Josephus would later write, “and others of them ran away wounded. An end was put to this sedition.”

To the Jewish people, Pilate is a villain. They think him “spiteful and angry” and speak of “his venality, his violence, his thefts, his assaults, his abusive behavior, his frequent executions of untried prisoners, and his endless savage ferocity.”

3

Yet one of their own is just as guilty.

* * *

Pontius Pilate cannot rule the Jewish people without the help of Joseph Caiaphas, the high priest and leader of the Jewish judicial court known as the Sanhedrin.

Caiaphas is a master politician and knows that the emperor Tiberius not only believes it important to uphold the Jewish traditions but is also keeping the hot-tempered Pilate on a very short leash. Pilate may be in charge of Judea, but it is Caiaphas who oversees the day-to-day running of Jerusalem, disguising his own cruel agenda in religiosity and piety. Few people in Jerusalem realize that the same man who leads the rite for the atonement of sins, appearing in the Temple courts on Passover and Yom Kippur wearing the most dazzling ceremonial robes,

4

is a dear friend of Rome and of the decadent emperor Tiberius.

The glamour of his position is most spectacularly evident during the annual Yom Kippur atonement ceremony, when Caiaphas enters alone a Temple sanctuary known as the Holy of Holies, where it is believed that God dwells. To Jewish believers, this places him closer to God than any mortal man. He then walks back out to stand before the believers who pack the Temple courts. A goat is placed on either side of Caiaphas. As part of the ritual atonement, this high priest must decide which goat will go free and which will be sacrificed for the sins of the Jewish people.

This same man who stands in the presence of God and sees that sins are forgiven is also the high priest who does not object when Pilate loots the Temple funds. Caiaphas also says nothing when Jews are massacred in the streets of the Holy City. He doesn’t complain when Pilate forces him to return those jewel-encrusted ceremonial robes at the end of each festival. The Romans prefer to keep the expensive garments in their custody as a reminder of their power, returning them seven days prior to each festival so that they can be purified.