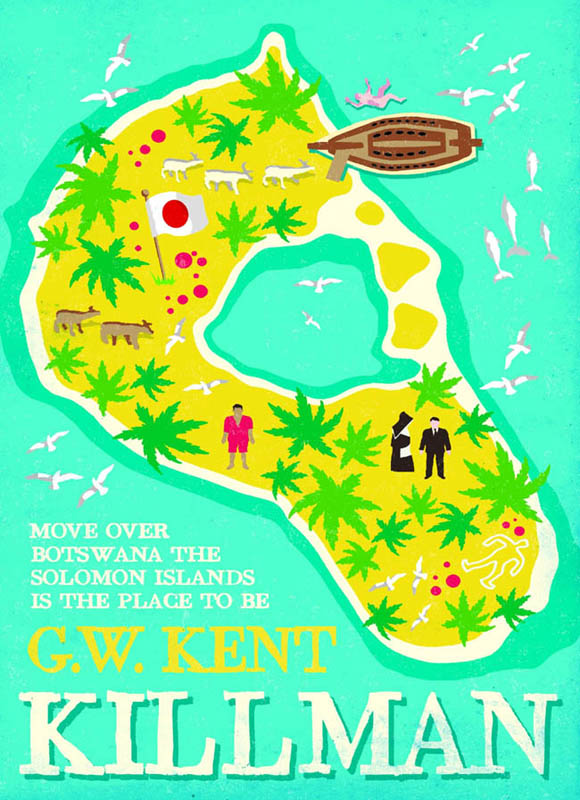

Killman

Authors: Graeme Kent

G. W. Kent

’s books have been published in more than twenty different countries. He has written fourteen novels, a number of critically acclaimed non-fiction books and several prize-winning television and stage plays. He has written and produced hundreds of radio plays and features for broadcasting organizations all over the world. As a freelance journalist he has written for many national newspapers and magazines. For eight years he ran an educational broadcasting service in the Solomon Islands. He lives in Lincolnshire.

A Sister Conchita and Sergeant Kella Mystery

G. W. Kent

Constable & Robinson Ltd

55–56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by C&R Crime,

an imprint of Constable & Robinson Ltd, 2013

Copyright © Graeme Kent, 2013

The right of Graeme Kent to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in

Publication data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-84901-342-0 (paperback)

ISBN: 978-1-47210-476-2 (ebook)

Printed and bound in the UK

Typeset by TW Typesetting, Plymouth, Devon

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Cover design:

boldandnoble.com

I am grateful to Markson Koroa for his help on my trip to Tikopia, and to Jimmy Kenekene and his family for their hospitality during my stays on the island of Savo. As always I am deeply indebted to my dedicated agent Isabel White for her unswerving understanding and enthusiasm. The charming and gifted editorial team at Constable & Robinson of Krystyna Green, Nicky Jeanes and Jane Selley has again contributed considerably. I am also conscious of how much I owe to Emily Burns and the sales, marketing and publicity departments for all their efforts on my behalf. My American publishers Soho Crime continue to be a source of much-appreciated enormous support and expertise.

JAPANI HA HA!

The twenty naked young virgins undulated slowly in front of Sister Conchita and the morose visiting female academic on the plateau next to the waterfall above the saltwater village. Beneath the enervating afternoon sun they were dancing the

tue tue

, the traditional Lau fishing song. Their fluttering hands raised above their heads depicted the graceful movement of frigate birds soaring over the canoes. Their sinuous, kicking legs represented the movement of fish leaping from the water to snap at bait dangling on hooks from kites attached to the imaginary gently rocking craft.

Sister Conchita wondered how the American researcher was reacting to the titillating entertainment on offer. At first glance she had seemed a little on the prissy side. From where she was sitting, Sister Conchita could no longer see the woman. Earlier she had caught a brief glimpse through the crowd of visitors of a thin white girl of about thirty in a nondescript blue dress. She had a pinched, discontented face and seemed uncertain of herself and uncomfortable in her exotic surroundings.

The pan-pipe music ended and the virgins stopped dancing with a flurry of smooth bare brown arms and legs. They stood giggling and revelling in their voluptuous nudity before their guests from all parts of the island. The entertainment was not yet over. Papa Noah, the custodian of the ark, clapped his hands. He was a fragile, grey-haired, almost fey man in his sixties, light on his capering feet and wearing a much-washed calico lap-lap extending from his waist to his knees.

A drum formed from a tree trunk with a hole gouged in the side started beating on the sidelines. The girls stopped undulating and stood to attention, composing themselves. In true, clear voices they began singing in pidgin, the lingua franca of the Solomons:

Me fulae olobauti, longo isti, longo westi.

Me sendere olo rouni keepim Solomoni

Me worka luka luka longo landi long sea

Ha ha! Ha ha! Japani ha ha!

Papa Noah clapped his hands again gleefully as he stood up. ‘No more tra-la-la! Time for our feast,’ he announced.

The virgins, glistening with perspiration in the hostile sun, broke ranks and ran back skittishly down the slope to the women’s house in the village below to dress. The hundred or so islanders who had been watching the dancing at the side of the waterfall scrambled to their feet and waited respectfully for the food to be carried across the clearing and placed on pandanus leaves on the ground. Some of them had walked for several days to attend the ceremony and were hungry. They showed no impatience; to do so would be regarded as impolite.

A raucous group of a dozen larger, lighter-skinned men sat a little to the left of the main gathering of guests, keeping a well-judged distance from them. Sister Conchita was sure that they came from the remote outlying Polynesian island of Tikopia. They had probably been working on one of the local plantations and were now waiting for a boat to take them home. They were ignoring the Melanesians at the ceremony but were chattering happily enough among themselves. There was a carelessly swaggering air to their posture. To fit the occasion they were determined to be happy, but they carried menace like a club and were capable of changing in an instant to something more dangerous but for them equally enjoyable.

It had been raining monotonously for several weeks, but there was a temporary lull in the downpour. The sun had eased through the clouds, causing a haze of steam to rise in tired exhalations from the wet grass. It was apparent that despite the threatening weather, the meal was going to be a sumptuous one. It was being prepared on the treeless plateau next to the waterfall, halfway down its leaping descent before the frothing, roaring water plummeted further down the rocks to the river a hundred feet below. At the far end of the plateau, trees and undergrowth grew thickly in almost impenetrable plenitude. This was where the jungle began. A steep, winding path led to the village below, built on the banks of the river where it ran out into the calm blue waters of the Lau Lagoon.

A dozen pigs had been slaughtered and quartered in advance. The grease-laden quarters were now being roasted over log fires on spits before being immersed in a sauce of grated coconut and milk. Chickens smothered in grated manioc were cooking in ovens scooped with clamshells out of the earth and covered with red-hot stones. A savoury vegetable broth was simmering in an iron cooking pot. There were piles of yams, taro and sweet potatoes, baskets of shellfish and bunches of bananas. As it was the pineapple season, pyramids of the fruit were scattered about.

Brother John, the gigantic Melanesian Mission travelling preacher, bullocked out of the trees and approached Sister Conchita, muttering an apology to Papa Noah for his tardiness as he passed him.

‘Did I miss anything?’ he asked the nun in low tones, surveying the scene before him. He was about thirty, six and a half feet tall and wide in proportion. His skin was a deep brown in colour. His face was broad and friendly, giving him the appearance of an affable bear, but one capable of being roused to rib-breaking retaliation by injustice or too much unnecessary torment. He wore the distinctive costume of his order, a black shirt and lap-lap and a broad black and white belt. The Melanesian Brotherhood was an Anglican sect, formed before the war by Ini Kopuria, a former policeman, who had adapted the then current police uniform for his evangelical order. Only Melanesians were permitted to join. Each volunteer brother spent a few years dedicated to poverty, celibacy and obedience, sometimes touring the islands, preaching and living off the land. The calm and imperturbable Brother John, Conchita knew, had been proselytizing in the Lau area of Malaita for almost two years, and should be coming towards the end of his tour of duty.

‘Just a couple of dances and a pidgin song,’ Sister Conchita told him, falling into step with Brother John as they walked towards the heaps of food.

‘I bet the song was the

tue tue

, the maidens’ fishing song,’ chuckled the big missionary. ‘It gives the girls a chance to get their kit off, and they like that, though not half as much as the boys do, of course. I’ve seen it performed all over Malaita.’ He paused. ‘Except on Sikaiana,’ he added.

‘Why not there?’ asked Sister Conchita. As soon as the words passed her lips she regretted them. She had given Brother John an opening, and she knew from experience that the big, rough-hewn man delighted in teasing young and inexperienced nuns from other orders, especially Roman Catholic ones.

‘They can never round up enough virgins on that island,’ said the Anglican pastor with a guffaw.

Sister Conchita resisted the temptation to laugh out loud. She struggled to maintain her habitual reserved expression. In the eleven months she had been at her mission station in the Solomon Islands, she had learned that if she could not seem old and wise, she could at least try to appear serene and above the fray, even if her current fate seemed to be acting as a straight woman to an overexuberant comic.

‘Which song did they sing?’ asked Brother John.

‘It was called “Japani Ha Ha!”. What’s it all about?’

‘It was a pidgin song of defiance that the Solomon scouts used to sing in the war when they were ambushing the Japanese troops in the bush,’ explained the huge Melanesian missionary in his deep operatic bass as the nun hurried to keep up with his raking strides. ‘It means

I keep watch everywhere, to the east and west, all over the Solomons. My duty is to guard the land and the sea against the invaders. I am not afraid. I laugh in scorn at the Japanese.’

‘Japani ha ha!’ nodded the nun. ‘But why sing that particular song here today? The war’s been over for fifteen years. There aren’t any Japanese left in the islands now, except for a few tourists now and again.’

‘I don’t know,’ said Brother John. ‘But I’m sure we’re going to find out. Just as I expect we’ll discover why Papa Noah has invited that American woman here with her recording device. The old man doesn’t do anything without a reason.’ He glanced at the dark clouds assembling threateningly over the sacred hill called Matakwalao. ‘Even if it means organizing a feast in the middle of the rainy season.’

Before Conchita could reply, she heard the scrawny woman’s voice complaining in petulant disappointment. She seemed to be arguing with Papa Noah on the far side of the clearing. Sensing trouble, Sister Conchita hurried over to try to defuse the situation. There was never any telling how easily an obtuse or arrogant visiting expatriate scholar might unwittingly offend against local protocol and upset the host tribe.

The white woman was plainly upset about something. The nun arrived in time to hear the tail end of her breathless protest, delivered in a New York whine. Sister Conchita noticed that the other woman was carrying a portable battery-operated Uher recording machine.

‘You promised me that there would be more songs,’ the thin woman was complaining. ‘That’s the only reason I agreed to come here today.’

‘I’m sorry, but there has been a change of plan,’ said Papa Noah placidly. ‘I know that you are particularly interested in pidgin songs of this island. Indeed, I particularly chose the one you have just heard to represent the unity showed by Solomon Islanders and your fellow countrymen from the USA when we fought the Japanese together here fifteen years ago. But I’m afraid there is no time for more music. We have a crowded timetable this afternoon.’

The woman turned away in obvious disappointment but said nothing else. She was not a fighter, decided the nun. Sister Conchita did not know what was going on, but she would have thought more highly of the other woman if she had stood her ground. She moved forward.