Kinglake-350 (8 page)

Authors: Adrian Hyland

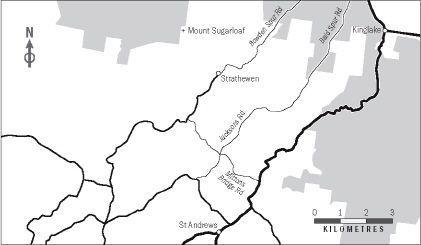

Paul Lowe takes Kinglake Tanker One hurtling down the bitumen and turns right into Mittons Bridge Road, bouncing over the corrugations. Dust spools behind them, is whipped away by the wind. The crew’s orders are to get to the fire at Strathewen, but they don’t have to: the fire comes to them. They’ve just travelled the couple of kilometres to the Jacksons Road intersection when the fire comes rushing over the paddocks from the north-west.

‘Jesus!’ spits Dave Hooper.

‘Where did that come from?’ mutters Lowe. They are still fifteen kilometres from their destination.

‘Grass fire attack!’ Hooper yells to his crew, meaning that they are to drive at the fire, attempt to suppress it. But as Aaron Robinson and Steve Nash leap out to man the hoses, Hooper realises the fire is moving at a speed he’s never seen before. It’s about to engulf them. ‘Back inside!’ he calls. ‘Crew protection!’

There are two types of truck on the fire front this day. On the older models, most of the crew are out on the back, exposed to the fury of the fire. The newer models have a twin-cab that seats the entire crew. The crew of Kinglake Tanker One have the good fortune to be in one of the modern tankers.

They’ve rehearsed this a hundred times, but can’t help wondering whether the real thing will run as smoothly. They scramble inside, draw the curtains, hit the spray button, lie low, brace themselves.

‘Here we go, boys,’ says Lowe calmly. ‘We’re into it.’

The flames come roaring up and over them. Their world is transformed into a flaming red singularity.

Lowe becomes concerned as the trees around them burst into flame: they’re throwing out massive blasts of radiant heat, and he’s worried that one of them could fall and entrap them. Mobility is one of your few defences in such a situation. He inches the truck through thick smoke, comes to an area that’s more open. They spend an agonisingly slow few minutes sheltering in their vehicle as it rocks and shudders, belted by the wind and battered by falling and flying debris. The men inside are panting and sweating in the heat, clutching wheel or handrail, giving the jesus grip a thorough workout.

‘Everybody okay?’ grunts Hooper. A couple of nods.

Then the intensity diminishes. They creep a little further along the road. Decide they’re going to survive.

Twenty-six years ago, in the Ash Wednesday fires, a dozen firefighters caught in a situation like this burned to death. The crew of Kinglake Tanker One won’t be joining them. The system has worked. All the training, all the efforts to develop more sophisticated operational practices—crews often rehearse for entrapment, and always ensure they leave enough water to save themselves—have paid off.

They still have a job to do, ‘putting the wet stuff on the red stuff ’ as Hooper expresses it, so they set about doing it.

A house on the hill opposite is surrounded by flames. Alerting

Vicfire as they jolt over the rough pasture, they race up to attack the flanks of the fire. The afternoon air rattles with the sounds of a fire fight: radio screaming chaos, pumps thumping, the jangle of metal, the hissing of water jets on flame, all in a haze of thick black smoke and mauling winds. And the strange distraction, as they crash around the paddock, of being followed by a mob of horses, who must have decided these yellow-helmeted aliens and their fat red truck are the closest thing to normal on this crazy day.

Other tankers arrive. Not a formal strike team, but local crews acting independently. The Kinglake crew work away until they run out of water, but now they hope the house is safe. As they go back to refill, they are joined by Kinglake Tanker Two, which has followed them down The Windies.

‘The radio was going berko as we drove into St Andrews,’ comments Ben Hutchinson. ‘Fires breaking out all over the place.’ There are tankers everywhere now, and a water truck belonging to local contractor Geoff Ninks is keeping them supplied. While Tanker One goes back to refill, Tanker Two patrols along Jacksons Road, its crew tackling whatever they can.

As is the case in any broad-scale conflict, the front-line fighters can only see what is happening in their little corner of the field, but they hear enough from the radio to know that things are going badly. And what they can see doesn’t look much better: no sooner do they get one spot under control than another flares up. The foothills of north St Andrews are being bombarded with flaming debris arcing in from the ridges around Strathewen, fires are breaking out everywhere. Hundreds of them.

‘Make tankers five,’ they hear the fire ground controller calling. Then it’s: ‘Make tankers ten!’ ‘Make tankers fifteen!’

They’ll take all the tankers they can get.

Fire spotter Colleen Keating is still in the observation tower at Kangaroo Ground, observing the battle as she has been from the beginning. Her own husband is on one of the trucks. At around 5.45 pm, those who are near a radio hear her calling:

‘Red Flag Warning!’

The Red Flag Warning system is a fire ground communications practice designed to alert firefighters to an imminent change in the weather. It was introduced after the Linton tragedy in 1998, when an entire CFA crew died after a sudden wind shift turned a tame flank into a raging killer.

Normally such a call would be issued by the Incident Control Centre at Kangaroo Ground, not by a fire spotter. But at that crucial moment the fighters on the fire ground were fortunate that a woman of Ms Keating’s initiative was in a position to make the call.

The spotters are a remarkable group of people. They are all experienced firefighters; they understand fire behaviour, they know the topography of their regions like their own weathered hands. They can triangulate a puff of smoke rising from a thick stand of distant forest to within a hundred metres. The firefighters on the ground entrust their lives to these people.

Mike Nicholls tells the story, from an earlier blow-up day, of the spotter who noticed a string of outbreaks along a remote St Andrews road, immediately recognised the work of a firebug and was confident enough to radio Vicfire straight away: ‘Make tankers ten!’ A big call, and something that would not normally happen until the local tankers were on the scene. By that time it would have been too late, the fires out of control.

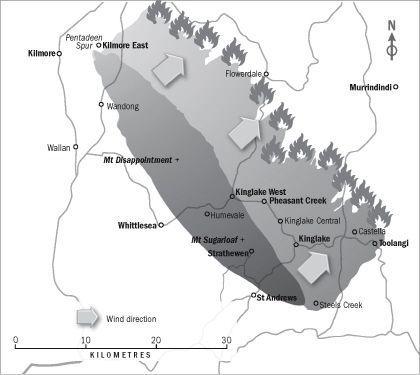

Communication systems were disintegrating in the chaos that was erupting all over the region, but Colleen Keating didn’t need the bosses to tell her that the chilling wind she could feel ripping past her lonely stone tower would have disastrous consequences for those out at the front. She’d spent the day transmitting increasingly desperate observations of the fire’s passage to the Kangaroo Ground ICC as the horror erupted before her startled eyes. She watched in disbelief at the size and speed of the thing as it came pouring over the slopes of Mount Sugarloaf and raced towards St Andrews: a mountain of smoke ten kilometres high, two wide.

All day the wind had been streaming down from the north-west. Suddenly, at around 5.45 pm, it swung around, roaring in from the south-west at ninety kilometres per hour, rattling her lookout something awful. She knew what that meant.

The southerly buster had arrived.

It had been forecast, but wasn’t expected for another hour or two. The experienced fire-ground controllers knew what would happen now. The northern flank of the fire would turn into the head and the inferno would go racing up the escarpment with an eruptive energy release anywhere between five and ten times that of the original blaze.

The wind change would prove to be a bullet dodged for the residents of Melbourne’s outer suburbs, a close escape most still don’t understand they had. At the time of the change, the firefighters on the front estimated the fire was two minutes from the town of St Andrews—the delaying operation carried out by the CFA crews on Mittons Bridge Road may well have saved the town. Given its speed, energy and direction, in another hour or two the inferno would have descended upon the tightly packed, overgrown suburbs of the northeast: Warrandyte, Hurstbridge, Diamond Creek, Greensborough, Eltham. If that had happened, the casualty figures would probably have been in the thousands, rather than the hundreds.

For Melbourne, it was a near miss. For the unwitting residents of the Kinglake Ranges, it was a catastrophe.

Colleen Keating, well aware of the implications, was aghast that this lethal change had arrived unannounced. ‘We didn’t get a pager to say there was a weather warning—weather coming early. We didn’t get a phone call,’ she would later tell the Royal Commission into the bushfires. ‘…It normally happens. next thing, bang, here is this wind…I could hear people I know on the fire ground and I’m thinking, Oh my god. This is Armageddon.’

The Kilmore East fire after the wind changed

So she broke protocol and issued the warning directly to her colleagues.

Viewed from almost anywhere other than the fire front—from, say, the comfortable perspective of the suburbs—the southerly buster feels like an enormous relief: it’s the long-awaited cool change. The temperature plummets, the sweat on your brow acts like air conditioning. Time to throw open the windows, let the refreshing breeze drift through the house.

But on the fire ground it’s the horror moment, the slo-mo sequence, the snake rearing in the grass. If you do think of it as a reptile, it may help to imagine it as one that is suddenly transformed from a single slithering serpent into a hydra-headed monster.

‘The change is the killer,’ comments senior meteorologist Tony Bannister. ‘When the wind was from the north-west, we had these long, thin slivers of fast-moving fire. But with the change, the flank becomes the head…The whole thing goes ballistic.’

Instead of a five-kilometre front heading south-east, you’ve got an eighty-kilometre front, and it’s rampaging all over the place. Historically, more than 80 percent of the destruction wrought by bushfires occurs after the cold front hits. Think of what your living-room fire does when you blow on it, then magnify that effect a trillion times over. A blast of cold air is driven into the heart of the storm; the fire turns upon itself—and comes across a massive source of untapped energy.

The very worst place, in time and space, is at the point of impact, when the weather systems collide. That’s when things on the fire ground go nuts. The vast majority of the vehicle burnovers on Black Saturday happened around that time. The flames go dancing in every direction and individuals are battered by blasts of wind, whips of flame, flying debris.

Fire historian Stephen Pyne describes this moment as ‘the deadly one-two punch, calculated to knock down by fire anything still standing after drought.’

That was how it had happened on the state’s previous disaster days: Black Friday, Ash Wednesday, Black Thursday. The northerly wind kick-starts the fire, drives it south, then the southerly change comes sweeping in and whips it into a frenzy. It will generally move to the north-east, but in those first few moments it is swept up into a vortex that can send its missiles spinning in every direction. This is why so many of Black Saturday’s victims reported that the fire came from directions they didn’t expect, from every quarter of the compass.

‘I felt like what we were fighting was a normal bushfire,’ recalls one Strathewen resident. It was still horrific, it still managed to destroy his house. But he and his family survived. ‘We were out of the house by then—watching it burn down. Everything around us was already burnt. Then the change came. I watched it change from a bushfire into a bomb. It swept up the slopes at a speed I couldn’t believe. Those poor bastards up there, they never had a chance.’

All over the fire ground, firefighters find themselves caught up in a gothic vision, a world gone mad. Trees bend to breaking point. Branches fly through the air like burning arrows. Wheels and whirls of fire dance across yellow paddocks. The tea-tree on the south-east side of Jacksons Road goes up like a plantation of monster sparklers, sending red, blue and purple fireballs sixty metres into the air. Some describe horizontal vortices—burning black holes—rolling along the flanks of the fire.

‘It was like a bloody tornado up there on Jacksons Road,’ commented one of the firefighters, and that was no exaggeration. The winds wouldn’t have seemed out of place in America’s Tornado Alley, only here they were more dangerous because they were loaded with fire.

The fire vortex is a well-known phenomenon, described by US fire scientist Clive Countryman in an account written forty years ago that is still regarded as a classic:

Moving air masses that differ in temperature, speed or direction do not mix readily. When they come into contact, a tearing or shearing action may be set up that can cause segments of the air in the boundary area to rotate and form eddies.

There are at least three wind types swirling around a bushfire: the dominant wind, which in this case is swinging from north-west to south-west, the convection column, and the air being sucked in to replace it. It’s the interaction between these three that kicks off the whirlwind.

The vortices in a fire can be anything from tens to hundreds of metres in height. Sometimes they might come spinning out from the flanks of a fire. At other times a large portion of the convection column itself can develop a sudden rotational motion. The physics at work is explained thus by meteorologist William Kininmonth:

It’s all about the concentration of angular momentum. Imagine an ice skater spinning. The skater develops a certain angular momentum by pushing on the ice and as the arms are drawn to the body the angular momentum is concentrated further and the body naturally spins faster. The air has a natural angular momentum due to the Earth’s rotation; if it is drawn into a small area by convection then the angular momentum is concentrated and the air tends to spin up.

Burning in whirls is five to six times more intense than burning in settled air and for those on the front line, it can be utterly terrifying.

Another extraordinary aspect of the fire at its most ferocious is that it can create its own weather.

CFA volunteer Andrew Brown commented: ‘They told us about fires, how they can make their own weather. Bullshit, I thought. Pull the other one.’ Then he watched, stunned, as the wind whipped up a maelstrom: the palls of smoke condensed into a fat pyrocumulus cloud that spat black rain into his face. There were crashes of purple lightning over the ranges, and a blast of wind blew him and his colleagues off their feet.

That a fire could create its own weather, that you could be lashed by black rain while in the middle of an inferno, might sound insane but it happens, and it is one of the factors that add to the chaos and confusion.

Again, it all comes down to convection. The same force that lifts heated air from the equator and regulates the Earth’s climate is responsible for the micro-climate that forms around a bush-fire. The convective updraft is of such strength that it will lift vast amounts of material—ash, embers—eight to ten kilometres into the atmosphere. Condensation starts to occur: any moisture in the vicinity, either in the elevated fuel or in the atmosphere itself, will accumulate around those microparticles of soot and ash. The air will become colder and heavier, lose its buoyancy. Eventually it gets so heavy that the column cannot hold it any longer, and it plummets back to Earth in the form of black rain. The lightning is a related phenomenon: the convection column is so unstable that it generates atmospheric friction and ultimately the cloud builds up more energy than it can carry, zaps it back to Earth in the form of electric bolts.

Sometimes this will be accompanied by terrible outdrafts of wind—hundreds of kilometres per hour—that come crashing out of the column and add to the chaos below.

Phillip Adams was crew leader on a Wattle Glen tanker. So powerful was the wind when the change came through, he could stay on his feet only by clasping the vehicle’s bull-bar with both arms. The wind ripped his uniform open, sucked the lenses out of his goggles and sandblasted his spectacles so badly that he spent the rest of the day half-blinded.

That incredible suction effect is an indicator of yet another wildfire phenomenon: the sharp drop in air pressure that occurs around the eye of the storm. One of the scientists interviewed for this book has heard of bushfire victims who’ve had their eyeballs sucked out by the force of the pressure differential.