Kleopatra

Authors: Karen Essex

This book is a work of historical fiction. In order to give a sense of the times, some names of real people or places have

been included in the book. However, the events depicted in this book are imaginary, and the names of nonhistorical persons

or events are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance of such nonhistorical persons

or events to actual ones is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2001 by Karen Essex

All rights reserved.

Warner Books, Inc.,

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

A Time Warner Company

First eBook Edition: April 2009

ISBN: 978-0-446-55961-4

Contents

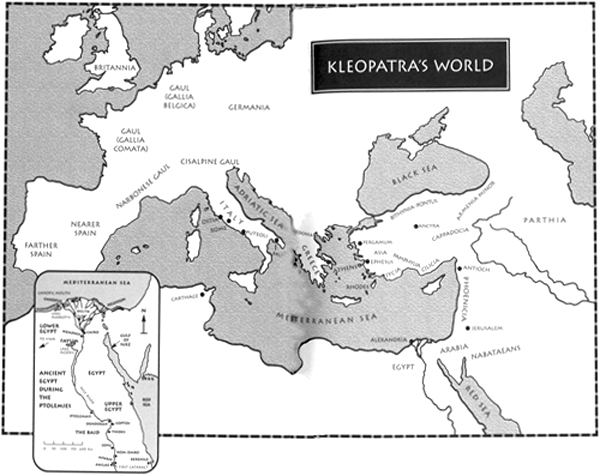

Part III: THE TWO LANDS OF EGYPT

Volume One is dedicated to the memory of

Professor Nancy A. Walker, and also to

my mother. Without the former’s intellectual guidance

and the latter’s generosity,

it may never have been completed

.

ALEXANDRIA

T

here was something about the air in Alexandria. It was said that the sea-god, Poseidon, who lived near the Isle of the Pharos,

blew a divine whisper over the town. Depending on his mood, he sent various sorts of weather. In the winter, the air might

be arid and unforgiving, so dry that it left old men gasping for breath and wishing for the balmy ether of spring. In the

summer, it hung over the city like a sea-damp gum. Sometimes it was but a carrier of flies and dust, and sometimes the harsh

winds of the African desert merely returned the sea-god’s breeze to its watery birthplace. But this morning, in spring disposition,

the god murmured a smooth rhythm toward the jewel-by-the-sea, teasing its way to the land, lifting the tender smell of honeysuckle

from the vine, and filling the air with essences of lemon, camphor, and jasmine.

In the center of town, at the intersection of the Street of the Soma and the Canopic Way, sat the crystal coffin of the city’s

founder, Alexander the Great. The Macedonian king had lain in his final resting place more than two hundred years, his youthful

mummy preserved against time so that all might pay tribute to his genius. Sometimes, the Egyptians would pull their sons away

from the coffin of the great warrior, forbidding them to say the prayer of Alexander’s cult taught in all schools, and scolding

them for their allegiance to foreign blood. But the dead Greek had envisioned this paradise, outlining in chalk the symmetrical

grid of streets. He had built the Heptastadion, the causeway that reached through the waters of the glimmering sea like a

long, greedy tongue, separating the Great Harbor from the Harbor of Safe Return. Alexander’s successors, the big-nosed Greek

Ptolemy and his children, had erected the Pharos Lighthouse, where the eternal flame burned in its upper tower like the scepter

of a fire god, guiding ships safely into the low, rocky harbor. They built the great Library that housed all the world’s knowledge,

the columned promenades that lined the paved limestone streets and shaded the pedestrians, and the city’s many theaters, where

anyone—Greek, Egyptian, Jew—could see a comedy, a tragedy, or a special oration. All in Greek, to be sure, but every educated

Egyptian spoke the language of the conqueror, though the favor was not returned.

The city was still a paradise, even if the once-great Ptolemies had degenerated into a new species—walrus-size monsters as

large as any creatures in the zoo, with appetites just as greedy. Sycophants who happily bled the Egyptian treasury to appease

the new Masters of the World, the Romans. Every few years, it was necessary for the Egyptian mob to assassinate at least one

Ptolemy, just to remind them that time brings down all races.

But on a day like today, where lovers nestled in shady groves of the Park of Pan, and stalky spring blooms jutted into a gaudy

lapis sky; where falls of white bougainvillea toppled from balconies like rivers of milk, it was easy to forget that the House

of Ptolemy was not what it used to be. Today, the god’s sweet sigh brought everyone into the streets to enjoy the parks and

promenades and open air bazaars. Today, everyone smiled as they inhaled the sea-god’s whisper. They did not care if it was

Greek air, Egyptian air, African air, or Roman air. It had no national character. It simply filled their lungs and made them

happy.

The Royal Family, whose ancestors had made the city great, saw none of this. The palace compound by the sea was a lone respite

from the city’s gaiety, its shutters closed tight against the delicious air and the extravagant day. Workers went about their

chores in silence, heads bowed like fearful worshippers. A thick haze of incense hung about the ceilings of the cavernous

rooms. All happiness had been shut out; the queen was ill, and the most famous physicians in the civilized world proclaimed

that she would not get better.

Kleopatra watched from her vantage point on the floor as the shimmering doors opened and the king rushed the blind Armenian

healer into her mother’s bedchamber. The girl’s eyes, sometimes brown but today green like baby peppercorns, widened as they

met the milk-white craters under the holy man’s brow. With tattered garments hanging about him like feathers, he hobbled toward

the child on what appeared to be two crooked sticks of kindling. Kleopatra leapt out of the way, barely escaping a swat in

the head from his saddlebags. She climbed onto the divan where her sister, Berenike, and her half sister, Thea, sat locked

in a silent embrace. Though neither moved, Kleopatra felt their flesh harden as she scampered to the end of the sofa and perched

herself on its arm.

“Should the little princess be present?” the Chief Surgeon asked the nurse, acting as if the child could not understand what

he said. “The situation is grave.”

Kleopatra’s mother, Queen Kleopatra V Tryphaena, sister and wife to the king, lay listless on the bed, gripped by a strange

fever of the joints. Frantic to keep his post, the Chief Surgeon had recruited physicians of great renown from Athens and

Rhodes. The queen had been sweated, bled, cooled with rags, massaged with aromatic oils, pumped with herbs, fed, starved,

and prayed over, but the fever won every battle.

“The child is headstrong,” whispered the nurse. “No one wishes to hear her incessant screaming when her will is challenged.

She is a headache. She is three years old and she cannot speak even one sentence of passable Greek.” They must have thought

she could not hear as well. Kleopatra jutted her bottom teeth as she did whenever she was angry.

“She is very small for her age. Perhaps she is slow to learn,” the physician pronounced, making Berenike laugh. The eight-year-old

sneered at Kleopatra, who glared back. “Her presence is always disruptive. I shall take it up with the king.”

The king—fat, melancholy, and agonizing over his wife’s mysterious illness—paid no attention to the physician. “The child

is exercising the royal will,” the king replied, his glazed, bulbous eyes staring at nothing. “Let her remain. She is my small

piece of joy.”

Kleopatra glowered victoriously at her sister, who kicked at her with a strong brown leg. Thea hugged Berenike tighter, stroking

her long coppery mane, settling her. The physician shrugged. Kleopatra’s father, King Ptolemy XII Auletes, had already sent

five doctors into exile. Others he simply abused for not curing his wife. If Kleopatra’s presence amused him, then all the

better. Perhaps no one would be slapped or dismissed or become the target of his verbal spew that day. He was a king famous

for his volatile temper. His subjects called him Auletes the Flute Player or Nothos the Bastard, depending on their mood and

mercurial allegiance to him. He preferred Auletes, of course, and adopted it as his nickname. Like his subjects’ loyalty,

his temper was notoriously changeable. But no one doubted that the king loved his sister-wife. It was said that theirs was

the first love match in the dynasty in two hundred years. The queen’s illness only heightened his choleric disposition.

The tonsured priest praying over the queen raised his slick head, astonished to see that the blind healer was to be given

access to the patient. With the attending physicians, he stood stationary, a human shield against the execrable creature.