Kornel Esti (27 page)

That sentence, which was in fact much more exhaustive and exhausting than that, he finished at two minutes past eleven.

Esti thereupon went to the wastepaper basket and took from it the latest, still uncut, number of

Moments and Monuments

. Dani thanked him for it, clarified a few secondary obscure points, and made to leave. Esti escorted him to the stairs. That did not pass off quickly either. When Esti had closed, locked, and bolted the gate behind him and returned to his room, his watch said that it was seventeen minutes past twelve.

In which he gives an appalling description of an everyday tram journey and takes his leave of the reader.

“

THE WIND WAS HOWLING,” SAID KORNÉL ESTI. “THE DARK

, the cold, and the night were lashing at my face with icy rods.

“My nose was a dark purple, my hands blue, my fingernails lilac. Tears were streaming down my face as if I were weeping, or as if such life in me as had not yet frozen into a solid mass of ice were melting. Black side streets yawned all around.

“I just stood and waited, stamping my feet on the rock-hard asphalt and blowing on my nails, hiding my numbed fingers in the pockets of my overcoat.

“Finally far away in the mist there appeared the yellow light-eye of the tram.

“The tram screeched along the rails. It took a slight bend and stopped in front of me. I was about to get on, but scarcely had I reached for the handrail than unfriendly voices shouted at me, ‘Full up!’ Bunches of people were hanging from the steps. Inside, in the doubtful red half-light of a single-filament bulb, living beings were moving, men, women, and children in arms.

“I hesitated for a moment, then with sudden decisiveness jumped aboard. I couldn’t afford to be fussy. I was so cold that my teeth were chattering. And then, I was in a hurry and had a long way to go; I simply had to get to my destination.

“My situation at first was more than desperate. I clung to the human bunch, and myself too became another indistinguishable grape. We hurtled over bridges and through tunnels at such a wild speed that had I fallen off, a terrible fate awaited me. Now and then I brushed against a wall, a wooden fence or a tree trunk. I was playing with death.

“The knowledge that my fellow passengers loathed me caused me greater suffering than the danger. Up on the platform of the tram they were laughing at me, but down on the step those to whom fate had welded me would clearly have greeted my falling off and breaking my neck with a sigh of relief—that’s what it would have cost them to be rid of a nuisance.

“It was a long time before I was able to get onto the platform. I found a tiny foothold on the very edge. But I was up there, on firm ground. I clung tightly with both hands to the rear of the car. There was no longer any need to be afraid of falling off.

“True, popular feeling turned against me again, and strongly. Down below I had become more or less used to it. My existence had been noted as a sad fact, and after a heated exchange no further attention had been paid to me. Up there, however, I was the next to force an entry, the newest enemy. They all united in burning hatred toward me. They greeted me openly and covertly, aloud and silently, with complaints, humorous curses, and coarse, despicable remarks. They made no secret whatever of the fact that they’d rather see me six feet underground than there.

“I didn’t give up the fight, however. ‘Just hold out,’ I encouraged myself. ‘Take the flak, don’t give in to it.’

“My obstinacy paid off. I got hold of a hand strap and hung from it. Soon someone pushed me, but I fell forward so luckily that I went farther inside. I was now no longer standing right by the exit but was wedged rock-solid in the very middle of the crowd standing on the platform. I was being crushed and kept warm on all sides. Sometimes the crush was so strong that I couldn’t breathe. Sometimes an object—an umbrella handle or the corner of a suitcase—poked me in the stomach.

“Apart from annoyances of a transitory nature, however, I couldn’t complain.

“Then my prospects gradually improved.

“People came and went, got on and off. Now I could move freely, unbuttoned my overcoat with my left hand, extracted my purse from my trouser pocket, and was able to satisfy the conductor’s repeated and solemn, but so far fruitless, appeals to buy a ticket. What a pleasure it was at least to pay.

“After that another little trouble arose. On climbed an imposing, fat inspector, whose 250 pounds almost caused the crowded tram to overflow like a brimful coffee cup into which a lump of sugar is dropped. The inspector asked for my ticket. Once more I had to undo buttons, this time with my disengaged right hand, and feel for the purse which I had only just put into my left trouser pocket.

“I was, however, definitely in luck. As the inspector forced a passage, bored a tunnel between the live bodies into the interior of the tram, a powerful surge of humanity swept me inward too and—at first I couldn’t believe my luck—I was in there, right inside the tram: I had ‘arrived.’

“In the process someone hit me on the head and a couple of buttons were torn off my overcoat, but what did I care about such things then? I swelled with pride at having got so far. There could, of course, be no question of a seat. I couldn’t so much as see the distinguished company of the seated. Those standing, straphanging, obscured them completely as they stood now on their own feet, now on other people’s, as did the vile fug, redolent of winter mist permeated by garlic-laden gastric exhalations and the sour effluvia of damp clothing.

“At the sight of this compressed and reeking herd, devoid of all human dignity, I was so disgusted that the thought haunted me of abandoning the struggle and not continuing my journey, close as I was to its end and achievement.

“At that moment, though, I caught sight of a woman. Poorly dressed, wearing a rabbit-fur stole, she was standing in one dimly lit corner and leaning on the side of the vehicle. She looked weary and woebegone. She had a simple face, a gentle, clear forehead, and blue eyes.

“When I felt the ignominy to be unbearable, when my limbs ached and my stomach churned, I would look for her in the rags, among the bestial faces, in the foul air, and play hide-and-seek among the heads and hats. Mostly she stared in front of her. Once, however, our eyes met. From then on she didn’t remain aloof. It seemed as if she too thought as I did, as if she knew what I thought of that tram and everything to do with it. This consoled me.

“She let me look at her, and I looked into her blue eyes as hospital patients look into that blue electric light which is lit at night in the ward so that they shall not be quite alone in their suffering.

“I have only her to thank that I didn’t finally lose my fighting spirit.

“A quarter of an hour later I actually found a place on the bench, which was divided into four seats by brass rails. At first I only had space enough to lower myself onto one thigh while the other dangled. Those sitting around me were horrid, small-minded persons, ensconced in their thick furs and the rights they had acquired, from which they would yield nothing. I made do with what they gave me. I made no demands. I pretended not to notice their paltry arrogance. I behaved like a sack. I knew that people instinctively hate people and are much quicker to forgive a sack than a person.

“So it was. When they saw that I was indifferent, the kind of nobody and nothing that didn’t count, they moved up a little and ceded a tiny bit of the seat that belonged to me. Later I was able to take my pick of the seats.

“A few stops farther on I obtained a window seat. I sat down and looked around. First I looked for the blue-eyed woman, but she wasn’t there—she’d obviously gotten off somewhere while I’d been engaged in life’s grim struggle. I’d lost her forever.

“I heaved a sigh. I stared through the frosted window, but all that I could see were lampposts, dirty snow, and darkly hostile closed gates.

“I sighed once more, then yawned. I consoled myself as best I could. I decided that I had ‘fought a good fight.’ I had achieved what I could. Who can achieve more on a tram than a comfortable window seat? I reflected and thought back almost contentedly over certain scenes in my terrible battle, the initial charge with which I had taken hold of the tram, the agonies of the step, the fisticuffs on the platform, the unbearable atmosphere and spirit inside the car, and I reproached myself for my lack of faith in all but losing heart and nearly retreating. I looked at the buttons missing from my coat as a warrior contemplates his wounds. ‘Everyone gets their turn,’ I repeated with the mellow experience of a philosopher, ‘you just have to wait.’ Rewards are not lightly bestowed on this earth, but nevertheless we receive them in the end.

“Now the desire came over me to enjoy my triumph. I was about to stretch out my cramped legs, finally to rest and relax, at last to breathe freely and happily, when the conductor came up to my window, turned round the destination board. and called out, ‘Terminus.’

“I smiled and slowly got off.”

Copyright © 1933 by Dezsó Kosztolányi

Translation copyright © 2011 by Bernard Adams

All rights reserved. Except for brief passages quoted in a newspaper, magazine, radio, television, or website review, no part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the Publisher.

Grateful acknowledgment to the Hungarian Book

Foundation, which supported the translation of this book.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Published simultaneously in Canada by Penguin Books Canada, Ltd.

New Directions Books are printed on acid-free paper.

First published as a New Directions Paperbook Original (NDP1194) in 2011

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kosztolányi, Dezso, 1885–1936.

[Esti Kornél. English]

Kornél Esti / Dezso Kosztolányi ; translated by Bernard Adams.

p. cm.

eISBN 978-0-8112-1958-7

1. Self-perception--Fiction. 2. Doppelgängers--Fiction.

3. Authorship--Fiction. 4. Psychological fiction.

I. Adams, Bernard. II. Title.

PH3281.K85E6713 2011

894'.51133--dc22 2010048874

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

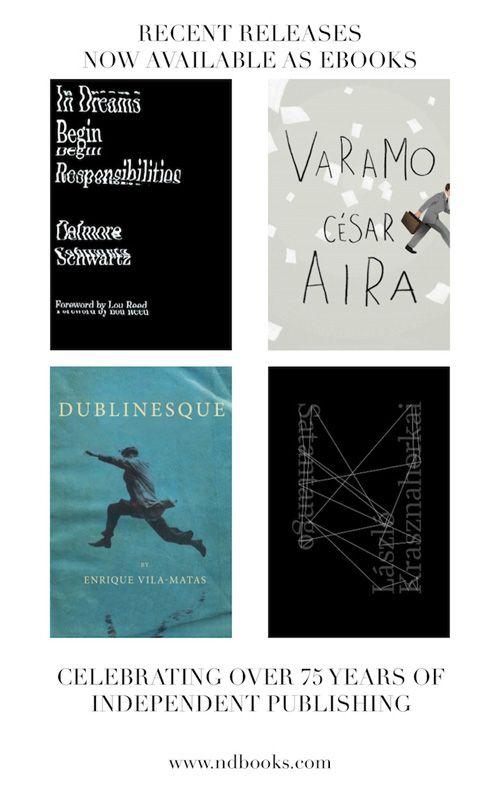

New Directions Books are published for James Laughlin

by New Directions Publishing Corporation,

80 Eighth Avenue, New York 10011

Also by Dezsó Kosztolányi

from New Directions

Anna Edes