Lad: A Dog (16 page)

Authors: Albert Payson Terhune

On the summit he lay down again to rest. Behind him, across the stretch of black and lamp-flecked water, rose the inky skyline of the city with a lurid furnace glow between its crevices that smote the sky. Ahead was a plateau with a downward slope beyond it.

Once more, getting to his feet, Lad stood and sniffed, turning his head from side to side, muzzled nose aloft. Then, his bearings taken, he set off again, but this time his jog trot was slower and his light step was growing heavier. The terrible strain of his swim was passing from his mighty sinews, but it was passing slowly because he was so tired and empty and in such pain of body and mind. He saved his energies until he should have more of them to save.

Across the plateau, down the slope, and then across the interminable salt meadows to westward he traveled; sometimes on road or path, sometimes across field or hill, but always in an unswerving straight line.

It was a little before midnight that he breasted the first rise of Jersey hills above Hackensack. Through a lightless one-street village he went, head low, stride lumbering, the muzzle weighing a ton and composed of molten iron and hornet stings.

It was the muzzleânow his first fatigue had slackenedâthat galled him worst. Its torture was beginning to do queer things to his nerves and brain. Even a stolid, nerveless dog hates a muzzle. More than one sensitive dog has been driven crazy by it.

Thirstâintolerable thirstâwas torturing Lad. He could not drink at the pools and brooks he crossed. So tight-jammed was the steel jaw-hinge now that he could not even open his mouth to pant, which is the cruelest deprivation a dog can suffer.

Out of the shadows of a ramshackle hovel's front yard dived a monstrous shape that hurled itself ferociously on the passing collie.

A mongrel watchdogâpart mastiff, part hound, part anything you chooseâhad been dozing on his squatter-owner's doorstep when the pad-pad-pad of Lad's wearily jogging feet had sounded on the road.

Other dogs, more than one of them, during the journey had run out to yap or growl at the wanderer, but as Lad had been big and had followed an unhesitant course they had not gone to the length of actual attack.

This mongrel, however, was less prudent. Or, perhaps, dog-fashion, he realized that the muzzle rendered Lad powerless and therefore saw every prospect of a safe and easy victory. At all events, he gave no warning bark or growl as he shot forward to the attack.

Ladâhis eyes dim with fatigue and road dust, his ears dulled by water and by noiseâdid not hear nor see the foe. His first notice of the attack was a flying weight of seventy-odd pounds that crashed against his flank. A double set of fangs in the same instant sank into his shoulder.

Under the onslaught Lad fell sprawlingly into the road on his left side, his enemy upon him.

As Lad went down the mongrel deftly shifted his unprofitable shoulder grip to a far more promisingly murderous hold on his fallen victim's throat.

A cat has five sets of deadly weaponsâits four feet and its jaws. So has every animal on earthâhuman and otherwiseâexcept a dog. A dog is terrible by reason of its teeth. Encase the mouth in a muzzle and a dog is as helpless for offensive warfare as is a newborn baby.

And Lad was thus pitiably impotent to return his foe's attack. Exhausted, flung prone to earth, his mighty jaws muzzled, he seemed as good as dead.

But a collie down is not a collie beaten. The wolf strain provides against that. Even as he fell Lad instinctively gathered his legs under him as he had done when he tumbled from the car.

And, almost at once, he was on his feet again, snarling horribly and lunging to break the mongrel's throat grip. His weariness was forgotten and his wondrous reserve strength leaped into play. Which was all the good it did him; for he knew as well as the mongrel that he was powerless to use his teeth.

The throat of a collieâexcept in one small vulnerable spot âis armored by a veritable mattress of hair. Into this hair the mongrel had driven his teeth. The hair filled his mouth, but his grinding jaws encountered little else to close on.

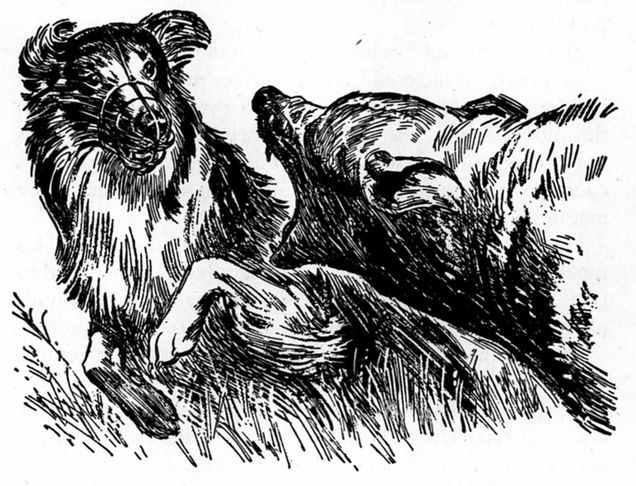

A lurching jerk of Lad's strong frame tore loose the savagely inefficient hold. The mongrel sprang at him for a fresh grip. Lad reared to meet him, opposing his mighty chest to the charge and snapping powerlessly with his close-locked mouth.

The force of Lad's rearing leap sent the mongrel spinning back by sheer weight, but at once he drove in again to the assault. This time he did not give his muzzled antagonist a chance to rear, but sprang at Lad's flank. Lad wheeled to meet the rush and, opposing his shoulder to it, broke its force.

Seeing himself so helpless, this was of course the time for Lad to take to his heels and try to outrun the enemy he could not outfight. To stand his ground was to be torn, eventually, to death. Being anything but a fool Lad knew that; yet he ignored the chance of safety and continued to fight the worse-than-hopeless battle.

Twice and thrice his wit and his uncanny swiftness enabled him to block the big mongrel's rushes. The fourth time, as he sought to rear, his hind foot slipped on a skim of puddle ice.

Down went Lad in a heap, and the mongrel struck.

Before the collie could regain his feet the mongrel's teeth had found a hold on the side of Lad's throat. Pinning down the muzzled dog, the mongrel proceeded to improve his hold by grinding his way toward the jugular. Now his teeth encountered something more solid than mere hair. They met upon a thin leather strap.

Fiercely the mongrel gnawed at this solid obstacle, his rage-hot brain possibly mistaking it for flesh. Lad writhed to free himself and to regain his feet, but seventy-five pounds of fighting weight were holding his neck to the ground.

Of sudden, the mongrel growled in savage triumph. The strap was bitten through!

Clinging to the broken end of the leather the victor gave one final tug. The pull drove the steel bars excruciatingly deep into Lad's bruised nose for a moment. Then, by magic, the torture implement was no longer on his head but was dangling by one strap between the mongrel's jaws.

With a motion so swift that the eye could not follow it, Lad was on his feet and plunging deliriously into the fray. Through a miracle, his jaws were free; his torment was over. The joy of deliverance sent a glow of berserk vigor sweeping through him.

The mongrel dropped the muzzle and came eagerly to the battle. To his dismay he found himself fighting not a helpless dog, but a maniac wolf. Lad sought no permanent hold. With dizzying quickness his head and body movedâand kept moving, and every motion meant a deep slash or a ragged tear in his enemy's short-coated hide.

With ridiculous ease the collie eluded the mongrel's awkward counterattacks, and ever kept boring in. To the quivering bone his short front teeth sank. Deep and bloodily his curved tusks slashedâas the wolf and the collie alone can slash.

The mongrel, swept off his feet, rolled howling into the road; and Lad tore grimly at the exposed underbody.

Up went a window in the hovel. A man's voice shouted. A woman in a house across the way screamed. Lad glanced up to note this new diversion. The stricken mongrel yelping in terror and agony seized the second's respite to scamper back to the doorstep, howling at every jump.

Lad did not pursue him, but jogged along on his journey without one backward look.

At a rivulet, a mile beyond, he stopped to drink. And he drank for ten minutes. Then he went on. Unmuzzled and with his thirst slaked, he forgot his pain, his fatigue, his muddy and blood-caked and abraded coat, and the memory of his nightmare day.

He was going home!

At gray dawn the Mistress and the Master turned in at the gateway of The Place. All night they had sought Lad; from one end of Manhattan Island to the otherâfrom Police Headquarters to dog poundâthey had driven. And now the Master was bringing his tired and heartsore wife home to rest, while he himself should return to town and to the search.

The car chugged dispiritedly down the driveway to the house, but before it had traversed half the distance the dawn hush was shattered by a thunderous bark of challenge to the invaders.

Lad, from his post of guard on the veranda, ran stiffly forward to bar the way. Then as he ran his eyes and nose suddenly told him these mysterious newcomers were his gods.

The Mistress, with a gasp of rapturous unbelief, was jumping down from the car before it came to a halt. On her knees, she caught Lad's muddy and bloody head tight in her arms.

“Oh, Lad!” she sobbed incoherently. “Laddie!

Laddie!”

Laddie!”

Whereat, by another miracle, Lad's stiffness and hurts and weariness were gone. He strove to lick the dear face bending so tearfully above him. Then, with an abandon of puppylike joy, he rolled on the ground waving all four soiled little feet in the air and playfully pretending to snap at the loving hands that caressed him.

Which was ridiculous conduct for a stately and full-grown collie. But Lad didn't care, because it made the Mistress stop crying and laugh. And that was what Lad most wanted her to do.

7

THE THROWBACK

THE PLACE WAS NINE MILES NORTH OF THE COUNTY-SEAT city of Paterson. And yearly, near Paterson, was held the great North Jersey Livestock Fairâa fair whose awards established for the next twelvemonth the local rank of pure-bred cattle and sheep and pigs for thirty miles in either direction.

From the Ramapo hill pastures, south of Suffern, two days before the fair, descended a flock of twenty prize sheep, the playthings of a man to whom the title of Wall Street Farmer had a lure of its ownâa lure that cost him something like $30,000 a year, and which made him a scourge to all his few friends.

Among these luckless friends chanced to be the Mistress and the Master of The Place. And the Gentleman Farmer had decided to break his sheep's fairward journey by a twenty-four-hour stop at The Place.

The Master, duly apprised of the sorry honor planned for his home, set aside a disused horse paddock for the woolly visitors' use. Into this their shepherd drove his dusty and bleating charges on their arrival.

The shepherd was a somber Scot. Nature had begun the work of somberness in his Highland heart. The duty of working for the Wall Street Farmer had added tenfold to the natural tendency. His name was McGillicuddy, and he looked it.

Now, in northern New Jersey a live sheep is well nigh as rare as a pterodactyl. This flock of twenty had cost their owner their weight in merino wool. A dogâespecially a collieâthat does not know sheep, is prone to consider them his lawful prey, in other words, the sight of a sheep has turned many an otherwise law-abiding dog into a killer.

To avoid so black a smirch on The Place's hospitality, the Master had loaded all his collies, except Lad, into the car, and had shipped them off, that morning, for a three-day sojourn at the boarding kennels, ten miles away.

“Does the Old Dog go, too, sir?” asked The Place's foreman, with a questioning nod at Lad, after he had lifted the others into the tonneau.

Lad was viewing the proceedings from the top of the veranda steps. The Master looked at him, then at the car, and answered:

“No. Lad has more right here than any measly imported sheep. He won't bother them if I tell him not to. Let him stay.”

The sheep, convoyed by the misanthropic McGillicuddy, filed down the drive, from the highroad, an hour later, and were marshaled into the corral.

As the jostling procession, followed by its dour shepherd, turned in at the gate of The Place, Lad rose from his rug on the veranda. His nostrils itching with the unfamiliar odor, his soft eyes outraged by the bizarre sight, he set forth to drive the intruders out into the main road.

Head lowered, he ran, uttering no sound. This seemed to him an emergency which called for drastic measures rather than for monitory barking. For all he knew, these twenty fat, woolly, white things might be fighters who would attack him in a body, and who might even menace the safety of his gods; and the glum McGillicuddy did not impress him at all favorably. Hence the silent charge at the foeâa charge launched with the speed and terrible menace of a thunder-bolt.

McGillicuddy sprang swiftly to the front of his flock, staff upwhirled; but before the staff could descend on the furry defender of The Place, a sweet voice called imperiously to the dog.

The Mistress had come out upon the veranda and had seen Lad dash to the attack.

“Lad!” she cried.

“Lad!”

“Lad!”

The great dog halted midway in his rush.

“Down!” called the Mistress. “Leave them alone! Do you hear, Lad?

Leave

them

alone

! Come back here!”

Leave

them

alone

! Come back here!”

Lad heard, and Lad obeyed. Lad always obeyed. If these twenty malodorous strangers and their staff-brandishing guide were friends of the Mistress he must not drive them away. The order “Leave them alone!” was one that could not be disregarded.

Other books

L'auberge. Un hostal en los Pirineos by Julia Stagg

Red-Hot Ruby by Sandrine Spycher

A Plea for Eros by Siri Hustvedt

Damaged by Pamela Callow

Sabine by A.P.

The Harriet Bean 3-Book Omnibus by Alexander McCall Smith

The Sibylline Oracle by Colvin, Delia

Morning Star: Book III of the Red Rising Trilogy by Pierce Brown

It Had Been Years by Malflic, Michael