Ladykiller

CANDACE SUTTON is a well-known Sydney journalist, who has covered major crime stories for many decades and has previously written the true crime thriller,

The Needle in

the Heart Murder

, for Allen & Unwin.

ELLEN CONNOLLY has been a journalist for almost two decades and has covered some of the biggest news stories in recent times including the Boxing Day tsunami and the Bali bombings. Previously with the

Sydney Morning Herald

and the

Sunday Telegraph

, she now writes for publications in Australia and the United Kingdom, including

The Guardian

.

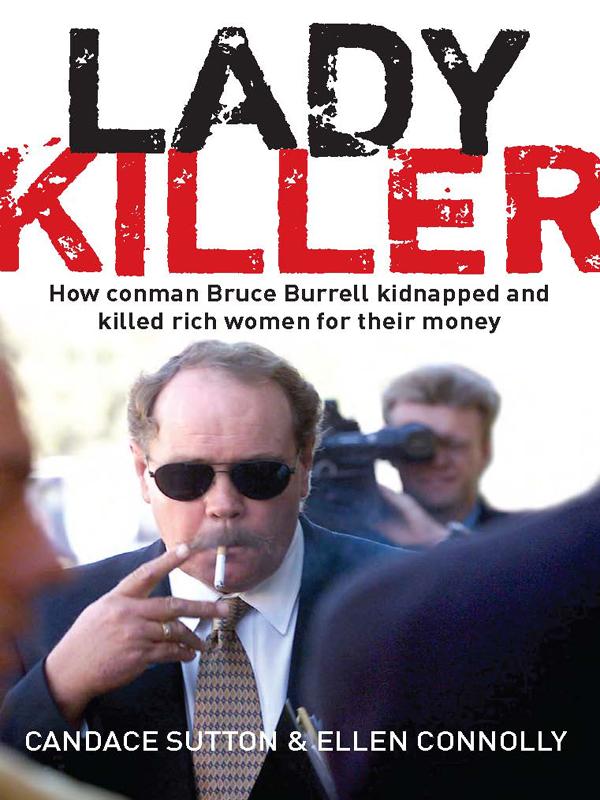

LADY

KILLER

How conman Bruce Burrell kidnapped and

killed rich women for their money

CANDACE SUTTON & ELLEN CONNOLLY

First published in 2009

Copyright © Candace Sutton and Ellen Connolly 2009

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The

Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Sutton, Candice, 1958- .

Ladykiller: how conman Bruce Burrell kidnapped and killed rich women for their money.

ISBN 978 1 74175 163 5 (pbk.).

1. Burrell, Bruce. 2. Whelan, Kerry. 3. Murder

investigation - New South Wales. 4. Criminal investigation

- New South Wales. I. Connolly, Ellen. II. Title.

364.152309944

Set in 11/14 pt Minion by Midland Typesetters, Maryborough, Australia Printed and bound in Australia by McPherson’s Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For the families of

Kerry Patricia Whelan and Dorothy Ellen Davis.

May their loved ones be returned to them.

CONTENTS

38 I did but see her passing by

46 The ten-million-dollar rip-off

We would like to give special thanks to all the people who gave generously of their time and expertise, and to those who spoke with us about the sensitive and personal matters this story entails. In particular, we wish to acknowledge the courage and honesty of members of the Whelan and Davis families. Some people have asked not to be identified. Their contributions were invaluable and we thank them as well as the following people for their kind assistance:

John Abernethy, Steve Barrett, Greg Bearup, Steve Benton, Mike Bowers, Detective Chief Inspector Dennis Bray, Michael Campbell, Peter Christopher, Michael Constable, Stephen Corby, Bruce Couch, Lessel Davis, Maree Dawes, Detective Darren Deamer, Allan Duncan, Gary Duncan, Stephen Gibbs, Sue Gladman, Rod Harvey, Mark Hobart, Mick Howe, Sandra Lee, Les Kennedy, Kate McClymont, John MacCulloch, Mick Maclay, Don McLennan, Gina McWilliams, Trish Miller, Steve Moorhouse, Marjorie Minton-Taylor, Sevinch Morkaya, Spiro Pandelakis, Amanda Peters, Sue Primmer, Sarah Rhodes, Donna Riley, Brett Ryan, Matthew Schramko, Clive Small, Joy Sutton, Mark Tedeschi, Frank Walker, Detective Sergeant Nigel Warren, Steve Warnock, Bernie Whelan, Debra Whelan, James Whelan, Matthew Whelan, Sarah Whelan, and Sue Whitfield.

A gunmetal-grey Jaguar Sovereign pulls up on Addison Street, Goulburn at Rugby Park where a large crowd is gathered in the autumn sunshine. It is mid-morning on Saturday 23 March 1996, the temperature hovering around 18 degrees Celsius.

At first glance, the Jaguar’s driver seems reasonably well-to-do. He is dressed in a variation of what the local graziers wear: elastic-sided boots, jeans, a double-pocketed shirt and V-necked jumper. He is a farmer perhaps, although not quite a member of the ‘squattocracy’, and the look on his plump face is smug. The Jag is covered with a patina of dust after the 22-kilometre trip north-west from his rural estate and has a respectable amount of earth stuck to the mudguards.

Bruce Allan Burrell walks into the chattering throng gathered to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the town’s rugby union club, the Dirty Reds, and heads for the bar. More than eight hundred locals and visitors from Canberra, the Southern Highlands and Sydney will turn up on this day to honour one of its golden sons. Families sit on rugs scattered on the grassy banks and groups of men and young people stand around drinking. The mood is triumphant in the town, Australia’s one-time wool industry capital and one of Australia’s wealthiest inland cities. All across the region, after years of middling results, wool prices are set to rise.

At 1.50 p.m., Goulburn will name a former chunk of Crown land along Addison Street after its most illustrious sporting product, rugby international Simon Poidevin. The Federal Minister for Transport and Member for Hume, John Sharp, will dedicate the field and then run onto it during a golden oldies game, one of five that afternoon to christen the hallowed turf. The doyen of rugby commentators, Gordon Bray, will referee the afternoon’s showcase: a Simon Poidevin XV versus a President’s XV tribute match. The ground is thick with local rugby talent, including Goulburn first graders and club greats from yesteryear ready to pit themselves in the president’s side against a team headed by the former Wallaby breakaway. Spectators are promised a free-flowing Barbarians style of play, a hard and fast game in which kicking will be virtually taboo.

On this auspicious day, Bruce Burrell feels he justifiably belongs. He is himself a former Goulburn rugby player, a tall, barrel-chested and, by all accounts, fair-playing second rower in the juniors teams of the 1960s. He is now forty-three years old, with receding reddish-brown hair, and is running to fat around his middle, a result of inactivity and a lust for beer. Bruce Burrell loves drinking beer, stubbie after frosty stubbie of Victoria Bitter, mostly.

He has brought to Goulburn his wife, Dallas, and his greatest supporter, his father Allan. Bruce wants his father to believe he is a successful country gentleman who has the properties and lifestyle to prove it. He leads Dallas and Allan through the crowd to some old rugby acquaintances. Bruce wastes no time dropping into the conversation that his Jaguar is parked outside. He slips the boast in several times, then moves on to his career as a city advertising executive.

Dallas nods as her husband spins a few stories about his prowess in the advertising field. She works in advertising too. Bruce explains to the group that he divides his time between a seaside apartment and his property, 160 kilometres south of Sydney, at Bungonia. When a new person joins the group, Bruce shifts the conversation back to his Jag and the houses.

A voice comes over the public address system. A group of men is gathering around a microphone on the field for the day’s official ceremony. By the time Simon Poidevin is ready to accept his hometown honour and cut a ceremonial ribbon, Burrell’s bonhomie is beginning to wear a little thin on his old ‘mates’, one of whom is Jeff Peterson, two years older than Bruce. ‘Peto’ is a schoolteacher, but he has some experience working in marketing. The two know each other from the Goulburn Rugby Club tournaments in which Jeff played in the under 16s and Burrell in the under 14s. Burrell regales him with stories of excitement and glamour in the Sydney advertising world, all featuring Bruce closing deals which make him rich. Peto has not had much to do with Bruce since the Burrell family left town in 1968, but he can tell he’s big-noting. Burrell is full of bullshit of the highest order, Peto thinks.

Nevertheless, everyone celebrating the newly christened Simon Poidevin field seems to be having a sensational day. Despite the best efforts of Simon Poidevin, who at thirty-seven is a fit and dashing-looking redhead, his side loses the game, 22-19 in a bone-jarring contest that does not live up to the prediction of a try-scoring fest. Just before full-time, the man of the hour is sent off after a brawl which the referee claims ‘Poido’ started. From a distance, the fracas appears to be staged for the crowd and Bruce boos merrily along with the others.

As the day wears on, Peto loses track of Bruce, who once upon a time played the game hard and fair on the field but has become, well, a bit of a wanker. Bruce was always a bullshitter, according to another of his old rugby friends, Spiro Pandelakis, but now it seems it’s too late to remind him: ‘Bruce, you’re talking to us!’

The revellers troop over for dinner in the great hall of St Patrick’s College, Poidevin’s alma mater. At 7 p.m., five hundred guests are seated; among them are Bruce, Dallas and Allan Burrell at a table with Bruce’s old school friend John MacCulloch and his wife, and Spiro and Judy Pandelakis. As the guests tuck into their plates of chicken, former Wallaby John Lambie warms them up with stories of rugby exploits in funny, foreign places, before he introduces Poido. The Goulburn crowd give their most prestigious export a rousing welcome. The night ends late, but happily, Jeff Peterson recalls. He will not hear from Bruce Burrell for another year.

Peto is not in a position to know the truth about his old football friend’s new life. He does not know it is practically all an illusion. For a start, the Jaguar is stolen and its registration plates belong to another stolen vehicle. Bruce’s marriage is a façade; his wife Dallas has decided to leave him because she can no longer handle his violent tirades. In two months’ time she will have moved out and without her financial support, Burrell’s cash flow will dry up. Contrary to the glittering business world Burrell purports to inhabit, in truth he has had no income of his own for three years. His bank account is practically empty, although he has cash secreted away, the remainder of the $100 000 he stole from a 74-year-old Sydney widow he killed. The thought of easy money brings a smile to his face. Bruce takes what he wants, does as he pleases, without the slightest sense of guilt or regret. He has no conscience and takes pride in his achievements, no matter how nefarious.

Bruce was questioned the previous year about the disappearance of Dorothy Davis, a kind of family ‘aunt’ to Dallas who lived around the corner from their ocean-view apartment. His alibi was never properly checked. Bruce delighted in getting away with the murder and credits his smooth talk and cleverness; he and Dallas made a good impression when they turned up in the Jaguar at the police station. The police are less likely to suspect a rich man with an apparently stable relationship. The police are pretty stupid, in his view.