Lamplighter (29 page)

Authors: D. M. Cornish

Stepping onto the tiny landing, Rossamünd looked up. He could see only a few flights above, beyond which darkness brooded. He listened: he could hear nothing but his own workings beating,

lub-dub lub-dub

.

lub-dub lub-dub

.

“You must go gently-gently,” said the glimner. “Some others are up here too, all a-wandering. I hear them sometimes down here but they don’t hear me. Oh no.” He took something from his satchel and pressed it into Rossamünd’s hands. “Here, Mister Rossamünd, take this; it’s too dark up there.” It was a small pewter box, like those in which pediteers carried their playing cards, but this had a thick leather strap attached and felt almost empty. The prentice did not know what to say.

“It’s a moss-light,” Numps explained. “Push—push at the top.”

Rossamünd did as instructed.The top panel proved to be a lid that, when slid up, exposed a diffuse blue-green glow within.With a closer look he found the box was hollow with a glass top, and stuffed with a bizarre kind of plant, its tiny leaves radiant with that odd, natural effulgence like bloom.

“So you will find the way.” Numps blessed Rossamünd with his crooked smile once more.

“Oh, thank you, Mister Numps.” Rossamünd felt a small relief: at least he would see his way—even if he was not certain

where

that way would lead him.

where

that way would lead him.

“Go, go.” Numps bobbed his head bashfully. “Up up to the top, slide the door, through the hole and off to bed just like me. Bye, bye . . .” Mumbling, he shuffled back along the reverse of his path.

By the eerie nimbus-light of Numps’ gift, Rossamünd began to climb the furtigrade. It was steep, of course, and so very cramped he was obliged to climb slowly. Heeding the warning that the glimner had given of others above, he worked hard to make his footfalls light and prevent the flimsy stair from creaking. Three flights and still the furtigrade went on. At the fourth the looming shadows resolved themselves into a doorway, but the stair went on.

No stopping at any doors, Mister Numps said.

Rossamünd continued to climb. His ascent was soon foiled, however. Not more than another two flights higher he discovered to his great dismay that a part of the stair had collapsed, making a wreck of gray splinters that made the furtigrade impassable. He could go no farther.

What now?

His mind’s cogs raced.

I’ll try the door I saw below.

No stopping at any doors, Mister Numps said.

Rossamünd continued to climb. His ascent was soon foiled, however. Not more than another two flights higher he discovered to his great dismay that a part of the stair had collapsed, making a wreck of gray splinters that made the furtigrade impassable. He could go no farther.

What now?

His mind’s cogs raced.

I’ll try the door I saw below.

Rossamünd crept down to this door, the glow of the moss-light muffled against his chest, and listened: nothing but drips and the rush of his heart. He dared a little more light and peered gingerly beyond the doorway. The floor of the space was a mirror of the ceiling, a broad shallow drain that formed a vaulted junction with three other tunnels. Forward or back he was lost, he figured, but back meant certain discovery and the pillory while forward at least held a chance of undetected return.

So forward it is . . .

So forward it is . . .

He had heard somewhere—probably from Master Fransitart—that when caught in a maze you should always go left and eventually you would win free. Taking a deep breath he went left. If this did not work he would simply return and choose again.

Rossamünd followed the leftward tunnel and it took him farther and farther from the junction, finally terminating in eight steps that led up to a brick wall.

A dead end!

But there, hammered into the mildewed bricks with corroded pegs of iron, was a crude ladder. Hanging the moss-light by its strap about his neck, the prentice scuttered up and pulled himself through into a deep tight valley in the masonry that smelled of century-settled dust and stillness. Brittle twig-weeds sprouted from any suggestion of a crack between floor and wall. How they managed to live at all down in this subterranean night he did not know.

A dead end!

But there, hammered into the mildewed bricks with corroded pegs of iron, was a crude ladder. Hanging the moss-light by its strap about his neck, the prentice scuttered up and pulled himself through into a deep tight valley in the masonry that smelled of century-settled dust and stillness. Brittle twig-weeds sprouted from any suggestion of a crack between floor and wall. How they managed to live at all down in this subterranean night he did not know.

Leftward was blocked by a wall, and so Rossamünd went right. In the meager moss-light, he thought he could discern what looked like the blank sockets of windows high in the walls above. Soon this architectural chasm ended bluntly in a redbrick barrier fronted by yet another furtigrade going up and going down. Up was closer to Winstermill, he reasoned, so he began to wearily climb again.

The night was never going to end!

I should never have come this way. I should have knocked on the Sally door . . . or even the front door.

Becoming used to this creeping dark, he took the ascent a little more confidently, but the stair sooned reached its end. At its summit he was confronted with a wall into which was sunk an oblong trap-hole, about his height and nearly an arm’s-length deep. It was blocked by a stained panel of dark rusted iron fixed with a corroded handle and barely held shut by a sliding bar of wood and iron. Rossamünd tried it in hope, and the flaking metal resisted at first but then slid back with a loud crack.

Maybe this is the door Numps was thinking of . . .

He tugged, and the door did not shift. He shoved with hearty frustration, and in a small burst of rusting dust from its age-blackened hinges the portal bulged inward—just a little. Through this crack was a glimpse into blackness, and from it exhaled the foul odor of decay, so much like that far worse hint he had once detected in the hold of the

Hogshead.

In the bowels of the cromster it had been heavily masked with swine’s lard, but here it was full and oppressively potent, smothering him in its dread stink.

Maybe this is the door Numps was thinking of . . .

He tugged, and the door did not shift. He shoved with hearty frustration, and in a small burst of rusting dust from its age-blackened hinges the portal bulged inward—just a little. Through this crack was a glimpse into blackness, and from it exhaled the foul odor of decay, so much like that far worse hint he had once detected in the hold of the

Hogshead.

In the bowels of the cromster it had been heavily masked with swine’s lard, but here it was full and oppressively potent, smothering him in its dread stink.

A rever-man!

he intuited, stepping away from the door.

Down here? But how?

He could not believe it.

he intuited, stepping away from the door.

Down here? But how?

He could not believe it.

There was a sound, some nondescript evidence of motion; a step, a shuffle—Rossamünd could not tell, but he knew something moved behind that stubborn-hinged door.

I must try another way!

He reached for the handle of the panel to shut it.

He reached for the handle of the panel to shut it.

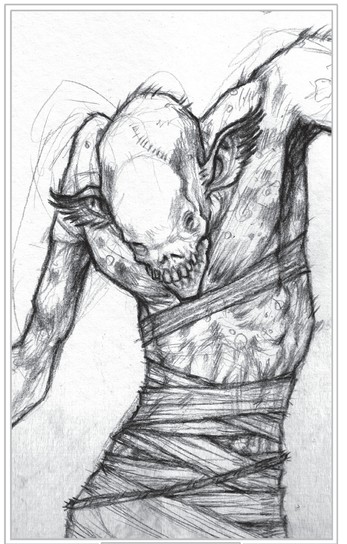

Some misshapen thing lurched at the space from the black within. Pallid hands, blotched and scabbed, gripped door and post and wrenched powerfully. Metal groaned, wood buckled and the door-gap widened. A pale head thrust through, craning and twisting right, then left, its spasmodic breath coming in a quivering wheeze. Its toothy, lipless mouth seeped saliva, at which it sucked almost as often as it breathed. The abominable creature twisted about and fixed its callous attention on him, pinning him with its morbid fascination.With a white flash of dread he realized this was a gudgeon. Here truly was a

rever-man

—uncaged, unfettered, dreadfully free.

rever-man

—uncaged, unfettered, dreadfully free.

Rossamünd bit back a scream. His innards churned. His thoughts wailed.

A rever-man! A rever-man here in Winstermill!

A rever-man! A rever-man here in Winstermill!

For a breath Rossamünd’s mind was overthrown as he tottered back, struggling to fathom what he saw.Yet with the cold, radiating dread that cried

Run! Run!

in a tiny, terrified voice within came a wholly unexpected rage. Faced now with a rever-man, a blasphemously made-thing, uncaged and visible, Rossamünd’s terror did not overcome him. His hand went instinctively to his salumanticum and found the Frazzard’s powder.

Run! Run!

in a tiny, terrified voice within came a wholly unexpected rage. Faced now with a rever-man, a blasphemously made-thing, uncaged and visible, Rossamünd’s terror did not overcome him. His hand went instinctively to his salumanticum and found the Frazzard’s powder.

The gudgeon shifted its grasp. Tiny little piggy eyes regarded him coldly—soulless, dead—as slowly, inexorably the panel-door was forced open. Large, furry, inhuman ears swiveled and twitched at either side of its long and bulging skull. Swathes of filthy bandages and even a rope were wrapped about its trunk, keeping its heaving chest and stitch-grafted abdomen together. What struck Rossamünd most was the utter absence of any threwd about the thing.

A threwdless monster: how could you ever tell it was coming?

Indeed, it was devoid of even a flicker of real vitality: a man-made thing, a dead thing.Yet its full and putrid reek, unmasked by swine’s lard, was potent. The gudgeon opened its slavering mouth and a long tongue like a lizard’s lolled obscenely, flicking in the dusty air. Even as Rossamünd stumbled backward onto the furtigrade and down the way he had come, the abomination stared with hungry curiosity as the crack between door and wall grew ineluctably wider.

A threwdless monster: how could you ever tell it was coming?

Indeed, it was devoid of even a flicker of real vitality: a man-made thing, a dead thing.Yet its full and putrid reek, unmasked by swine’s lard, was potent. The gudgeon opened its slavering mouth and a long tongue like a lizard’s lolled obscenely, flicking in the dusty air. Even as Rossamünd stumbled backward onto the furtigrade and down the way he had come, the abomination stared with hungry curiosity as the crack between door and wall grew ineluctably wider.

“Hmm,” it seethed, licking at the gap between it and the prentice, “yooouuu mmmake mmeee huuunnngreee . . .”

With one powerful spring, the made-monster flung itself through the gap, viper-quick, at Rossamünd, slamming into the balustrade as it made pursuit.

Tripping, nearly falling, Rossamünd blundered down the stair. The gudgeon staggered and turned with a dry, rattling hiss. On the lower landing Rossamünd twisted and flung the potive at it as it pounced at him from on high. His aim was as true at a natural throw as it was off with a firelock. The Frazzard’s powder burst against the creature’s neck and shoulder with a flash of bluish sparks and a series of tight detonations that sounded like the popping of corks.

“Aaiieeee!”

The creature hit the wooden steps with a crash and tumbled into Rossamünd as it fell. A thousand stars erupting across his senses, the prentice was crushed over and over between wooden step and rever-man. Together they toppled a whole other flight, then another, striking the banister rail on the lower landing hard, causing it to crack dangerously.

The creature hit the wooden steps with a crash and tumbled into Rossamünd as it fell. A thousand stars erupting across his senses, the prentice was crushed over and over between wooden step and rever-man. Together they toppled a whole other flight, then another, striking the banister rail on the lower landing hard, causing it to crack dangerously.

The gudgeon was on him in an instant, pressing him down, its whelming stench all about him, teeth snapping

clack! clack!

seeking to nip at exposed flesh: fingers, knees, cheeks. In white, blind terror Rossamünd heaved the abominable creature off and shoved it—almost threw it though it was twice his size—across the tiny landing. Free of its imprisoning bulk, he sprang up the stairs he had just descended so painfully, pointlessly crying,

“Help! Help!”

clack! clack!

seeking to nip at exposed flesh: fingers, knees, cheeks. In white, blind terror Rossamünd heaved the abominable creature off and shoved it—almost threw it though it was twice his size—across the tiny landing. Free of its imprisoning bulk, he sprang up the stairs he had just descended so painfully, pointlessly crying,

“Help! Help!”

“Ahhh! Yoouuu liiittle beeeast!” he heard it hiss behind him.The rever-man was fumbling about on hands and knees, its piggy little eyes burned out by the Frazzardian chemistry. The distinct peppery-salty smell of the spent potive spiced the close fug of the furtigrade. “I caaan stiiill heeeaaaarrrr yoouuu . . .”

The gudgeon shuffled toward Rossamünd and he turned to face it, scuttering up each step upon his bottom.

It made a strange cackling. “I could eeeat

yoouurrr

kiiind aaall the looong looong daayyy!” It sprang catlike at what it believed to be Rossamünd’s position, and struck the banister three steps below the prentice with enough force to smash the rails to flinders, which toppled down into the darkness. Nothing could stop the gudgeon. It bounced off the ruined wood, its arm a spasming dead weight, the left shoulder dislocated and deformed by the blow—the vile creature so utterly ravening it was destroying itself to get to him. It pounced again.

yoouurrr

kiiind aaall the looong looong daayyy!” It sprang catlike at what it believed to be Rossamünd’s position, and struck the banister three steps below the prentice with enough force to smash the rails to flinders, which toppled down into the darkness. Nothing could stop the gudgeon. It bounced off the ruined wood, its arm a spasming dead weight, the left shoulder dislocated and deformed by the blow—the vile creature so utterly ravening it was destroying itself to get to him. It pounced again.

Rossamünd kicked out with all the might his horror could muster—and missed. The unhallowed thing gripped his flailing leg and bit at his shin, a bite meant to tear away muscle. Its crooked teeth met proofed galliskins, cruelly pinching flesh against bone but failing to penetrate. Once again Rossamünd had been saved by the wonders of gauld. With a yelp, he lashed with his free leg, striking the putrid thing upon its face. The gudgeon must not have been well knit, for its jaw gave way with sickening ease under his boot-heel; teeth sprayed and clattered about the stair. The cobbled-together thing gurgled and shrieked and sought to grasp Rossamünd in a death grip. Kicking again, the prentice got his footing and bounded up the stairs.

Below, the gudgeon was hissing and sucking through its mangled mouth, struggling once again up the furtigrade seeking nothing but gory murder, utterly heedless of its broken parts.

THE GUDGEON

Rossamünd extracted another salpert of Frazzard’s powder.

Oh, for something more deadly!

Yet he did not dare use the loomblaze for fear it would cause the dry, dusty furtigrade to take fire, and start an unstoppable conflagration right within the foundations of the manse. He threw the potive hard on the step before the gudgeon, seeking to make a brief barrier, to give the abomination second thoughts.The potive popped and crackled as it erupted and sprayed the gudgeon again. With its cries of rage oddly flat and muffled in the squeeze of the dusty furtigrade, Rossamünd dashed up the stairs, pain jarring up his bitten shin.

Oh, for something more deadly!

Yet he did not dare use the loomblaze for fear it would cause the dry, dusty furtigrade to take fire, and start an unstoppable conflagration right within the foundations of the manse. He threw the potive hard on the step before the gudgeon, seeking to make a brief barrier, to give the abomination second thoughts.The potive popped and crackled as it erupted and sprayed the gudgeon again. With its cries of rage oddly flat and muffled in the squeeze of the dusty furtigrade, Rossamünd dashed up the stairs, pain jarring up his bitten shin.

The foul thing was staggering up after him—he could see it through the frame and rails—eyes fizzing, weeping gore, utterly ruined by two doses of Frazzard’s powder, jaw a crooked mass, mouth dribbling unstoppably. There was something almost pathetic about this abominable creature with its terrible injuries, yet it did not heed its damage. With long, clumsy reaches of its arms, the gudgeon slapped its hands on a higher step, felt the way and pulled itself up, gaining pace. There was no escaping the thing. Rossamünd could only try to flee up the furtigrade and out into the unknown cavities of the vault above.

“Help!”

he cried, a small pathetic sound in this claustrophobic fastness.

he cried, a small pathetic sound in this claustrophobic fastness.

The gudgeon slunk around the landing below, starting up the very stair he was upon. It jabbered at him incomprehensibly, trying to form vile taunts with its broken, dribbling maw.

“Help!”

Rossamünd bellowed again. He knew it was hopeless, but sanguine hope kept him crying.

Rossamünd bellowed again. He knew it was hopeless, but sanguine hope kept him crying.

He set his feet on the creaking boards of the tiny landing by the wrenched door, giving himself a little space to fight from, and seized a caste of loomblaze from his salumanticum. He had to risk it or perish. Rossamünd watched the ill-gotten thing climb, and waited. Waited till it was close enough.

Other books

Cataract City by Craig Davidson

How to Look for a Lost Dog by Ann M Martin

Brond by Frederic Lindsay

Captive Wolf (Werewolf Erotic Romance) (Amber in Darkness #1) by Reyer, Julianne

Silence of the Wolf by Terry Spear

A Biker and a Thief by Tish Wilder

Fat hen farm 01- Killer tracks by Sandy Vale

Appointment in Samarra by John O'Hara