Lark's Eggs (31 page)

Authors: Desmond Hogan

During the day I noticed his hair had copper in it.

One evening during spring tide I saw him stand in a

rose-coloured

shirt, not far from cottages, by the river where it was

bordered

by yellow rocket float down.

The first poppy was a bandana against the denim of the bogs of West Limerick.

In the evenings of spring tide when the Travellers came along and swam their horses I was reminded of St Maries which I'd visited

twenty years before, when the Gypsies would come and lead their horses to the water on the edge of the Mediterranean. To Saintes Maries had come Mary, mother of James the Less, Mary Salome, mother of James and John, and Sarah, the Gypsy servant, all on a sculling boat. There were bumpers by the sea and in little dark kiosks jukeboxes with effects on them like costume jewellery. Lone young Gypsy men wandered on the beach, great dunes on the land side of the beach. A little inland horsemen with bandanas around their noses rode horses through the Camargue.

Back briefly in the river pool one evening I found the Traveller youth with the cavalier hair shampooing himself after a swim. His underpants were sailor blue and white.

Later that week when I came to Gort the boy with the

primrose-flecked

hair was there alone with his horse, a Clydesdale, ruffs at his feet. A few days' growth on his face, he was naked waist up. There was the imprint outline of a tank topâthe evidence of hot days, his

nipples

not pinkâhazel, a quagmire of hair under his arms, freckles berried around his body. His body smelt of stout like the bodies of young men who gathered in my aunt's pub in a village in the Midlands when I was a child. A rallying, a summoning in the body to dignity.

I am in the West of Ireland, I thought. Illness prevents me from seeing, from looking. Like a soot on the mind. Sometimes I raise my head. Like Lazurus recover lifeâespecially vision.

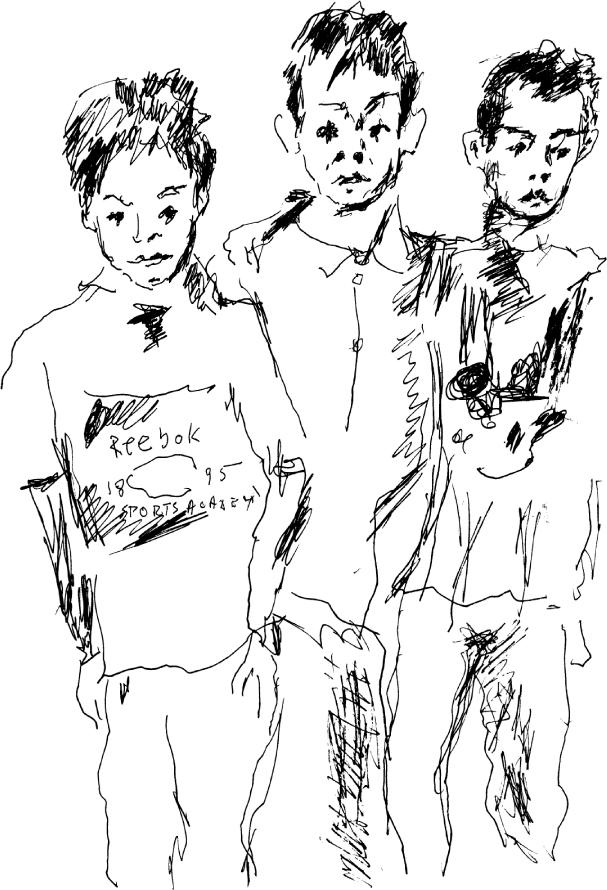

One Friday evening as I cycled home from Gort the youth with the primrose-flecked hair introduced himself. âCummian.' And he introduced the other two youths. âGawalan. ColÃn.'

âYou need a relationship,' he said.

When the tide came in in the evening again his horse had a wounded leg and he tied it to the ship rung on the pier and it would stand in the water for hours. Cummian stayed with it and he'd watch me swim and between swims he'd tell stories.

âThere was a man who fucked his mares. He tied them to trees.'

âSomeone sold a horse to a man who lived on Cavon Island off Clare and the horse swam back across the Shannon estuary to West Limerick.'

Two Traveller brothers troubled over a horse at Gort, their voices becoming muffled. They seemed to wager the tide. The river had aÂ

mirror-like quality after rain. Late one evening Cummian was sitting in the bushes to one side with some men, one of whom was holding up a skinned rabbit. Boys would often fish on the pier with the triple hookâthe strokeallâfor mullet. On the far side young men would hunt for rabbits with young greyhounds. On summer nights

Travellers

would draw up on the pier in old carsâFord Populars,

Sunbeams

. In Scots Gaelic there's a word,

duthus

âcommonage. That's what Gort was, people coming, using the place in common. The winter, the dark days were a quarter I thought, now I have to face people, I have to communicate. There was often a bed of crabs on the river edge as I walked in.

âIf I wasn't married, I'd get lonely,' said Cummian one evening.

Water rats swam through the water with evening quiet, paddling with their forepaws. The tracks of the water rat made a V-shape.

Sometimes in the early evening there'd be a harem of Traveller boys on the pier in the maple red of Liverpool or the strawberry and cream of Arsenal or the red white of Charlton

FC

or the grey white of Millwall

FC

.

âWhere are you from?' asked a boy in a T-shirt with Goofy playing basketball on it.

âYou don't speak like a Galwayman but you've got the teeth.'

Cummian would tell stories of his forebears, the Travelling peopleâbeet picking in Scotland, âWe lie down with manikins.' That ancestor used write poems and publish them in

Moore's Almanac

for half a crown.

Sometimes he got four and six pence. âSome of them were a mile long,' said Cummian.

âThey used stuff saucepans with holes with the skins of old potatoes and they'd be clogged. They used milkcans especially. Take the bottoms out of milkcans. Put in new ones.'

With his talk of mending I thought, recovery is like a billycan in the hand, the frail, fragilely adjoined handle.

In the champagne spring tide of late July Cummian rode the horse in a bathing togs as it swam in the middle of the river.

One afternoon there was a group of small boys on the pier fishing. One had a Madonna-blue thread around his neck, his top naked, his hair the black of stamens of poppies.

âI'll swim with you,' he said, âif you go naked.' I took off my togs. They had a good look and then they fled, one of them on a bicycle, in a formation like a runaway camel.

Sometimes, though rarely, Traveller girls would come with the boys to the pier, with apricot hair and strawberry lips, in sleeveless, picot-edged white blouses, in jeans, in dresses the white of white tulips. Cummian's wife came to the pier one evening in a white dress with the green leaves of the lily on it, carrying their child.

Cummian was a buffer, a settled Traveller and lived in one of the cottages near the river, incendiary housesâcherry, poppy or rosette colouredâwith maple trees now like burning bushes outside them. There'd be horses outside the Travellers' cottagesâa jeremiad for the days of travelling.

One night Travellers were having a row on the green by the riverâthere was a movement like the retreat of Napoleon from Moscow, hordes milling across the green. Cummian, holding his child, looked on pacifically. âYou're done,' someone shouted in the throng.

There was a rich crop of red hawthorn berries among the

seaweed

in early fall, at high tide gold leaves on the river edge. Reeds, borne by the cork in them, created a demi-pontoon effect.

A woman in white court high heels came around the corner one day as I stood in my bathing togs. âThis place used be black with swimmers during high tide. Children used swim on the slope.'

A swan and five cygnets pecked at the bladderwort by the side of the pier and the cob came flying low up on the river, back from a journey.

In berry the pegwood, the berberis, the rowan tree were fairy lights in the landscape. The pegwood threw a burgundy shadow onto the water. With flood the reflection was the cinnabar red of a Russian ikon.

One day in early November Cummian was on the pier with his horse alongside a man with a horse who had a sedate car and horse trailer. The grass was a troubled winter green. The other man, apart from Cummian, was the last to swim his horse.

âHe likes winter swimming,' Cummian said of his. âLike you. He'd stay there for an hour. And he's only a year.'

With the tides coming in and going out there was a metallurgyÂ

in the landscape, with the tidal rivers a metallurgical feel, something extracted, called forth. A sadness was extracted from the landscape, a feeling that must have been like Culloden after battle. On Culloden Moor the Redcoats with tricornes had confronted the Highlanders.

âWhy do you swim in winter?' asked Gawalan who was with Cummian one evening.

âIt's a tradition,' I said, âI used to do it when I was a boy,' which was not true. Other people did it. I did it later, on and off in Dublin.

Jakob Böhme said the tree was the origin of the language. The winter swim sustains language I thought, because it is connected with something in your adolescenceâthe hyacinthine winter

sunlight

through the trees on the other side of the river. It is connected with a tradition of your country, odd peopleâapart from the sea swimmersâhere and there all over Ireland who'd bathe in winter in rivers and streams.

A rowing boat went down the river one afternoon in late November, a lamp on the front of it, reflection of lamp in the water.

Gawalan and ColÃn went to England. They'd go to see female stripteasers first in the city and then male stripteasers.

With November floods there were often piles of rubbish left on the riverbank. A man in a trenchcoat, with rimless-looking spectacles,

cycled up to the pier one evening. âI hear them dumping it from the bridge at midnight. It kills the dolphins, the whales, the turtles. You see all kinds of things washed in further down, pallets, dressers.' He pointed. âThere used be a lane going down there for miles and people would play accordions on summer evenings. A boxer used swim here with wings on his feet. There was a butcher, Killgalon, who swam in winter before you. He swam everyday up to his late eighties.'

The river's been persecuted, vandalized I thought, but continues in dignity.

Early December the horse swam in the middle of the river, up and down, and I swam across it. The water rubbed a pink into the horse.

Hounds, at practice, having appeared among the bladderwort on the other side, crossed the river, in a mass, urged on by hunting horns.

A tallow boy's underpants was left on the pier. Maybe someone else went for a winter swim. Maybe someone made love here and forgot his underpants. Maybe it was left the way the Travellers leave a rag, an old cardigan in a place where they've campedâa sign to show other Travellers they've been thereâspoor they call it.

Towards Christmas I met Cummian near his cottage and he invited me in. âWill you buy some holly?' a Traveller boy asked me as I approached it. Cummian's eyes were sapphirene breaks above a western shirt, his hair centre parted, a cowlick on either side.

There was a white iron work hallstand; an overall effect from the hall and parlour carpets and wallpaper and from the parlour draperies of fuschine colours and colours of whipped autumn leaves. He sat under a photograph of a boxer with gleaming black hair, in cherry satin-looking shorts, white and blue striped socks. On a small round table was a statue of Our Lady of Fatima with gold leaves on her white gown, two rosaries hanging from her wrist, one white, one strawberry; on the wall near it a wedding photograph of Cummian with what seemed to be a pearl pin in his tie; a photograph of

Cummian

with a smock of hair, sideburns, Dom Bosco face, holding a baby with a patina of hair beside a young woman in an ankle-length plaid skirt outside a tent.

We had tea and lemon slices by Gateaux.

Christmas Eve at the river a moon rose sheer over the trees like a medallion.

Christmas Day frost suddenly came, the slope to the water

half-covered

in ice. In the afternoon sunshine the ice by the water was gold and flamingo coloured.

Sometimes on days of Christmas the winter sun seemed to have taken something from the breast, the emblem of a robin.

Cummian did not come those days with his Clydesdale. I was the only swimmer.

I was going to California after Christmas. I thought of

Cummian's

face and how it reminded me of that of a boy I knew at national school, with kindled saffron hair which travelled down, smote part of his neck, who wore tallow corded jackets. His hand used to reach to touch me sometimes. At Shallowhorseman's once I saw his poignant nudity, his back turned towards me. He went to England.

It also reminded me of a boy I knew later who smelled like a Roman urinal but whereas the smell of a Roman urinal would have been tinged with olive oil his was with acne ointment. One day after school I went with him to his little attic room and he sat without a shirt, his chest cupped. There was a sketch on the wall by a woman artist who'd died young. He used often walk with his sister who wore a white dress with a shirred front and a gala ribbon to an

aboriginal

Gothic cottage in the woods.

He went to England in mid-adolescence.

He was in the

FCA

and would sit in the olive-green uniform of the Irish Army, his chest already manly, framed, beside a bed of peach crocuses on the slope outside the army barracks which used to be the Railway Hotel, a Gothic building of red and white brick, a script on top, hieroglyphics, the emblems of birds.

It snowed after Christmas. The trees around the river were ashen with their weight of snow. There were platters of ice on the water.

As I cycled back from swimming Cummian was standing with two Traveller youths in the snow. There was a druidic ebony

greyhound

in historic stance beside them. Their faces looked moonstone pale.

I knew immediately I'd said something wrong on my visit to Cummian's house. It didn't matter what I'd said, it was often that way in Ireland, having been away, feeling damaged, things often came out the way they weren't meant. Hands in the pockets of a monkey

jacket, hurt, Cummian's eyes were the blue that squared school

exercise

books when I was a child.