Las Christmas (14 page)

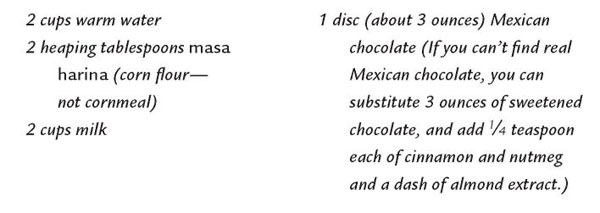

Hot Chocolate Atole

THICK HOT CHOCOLATE

Atole

is a hot cornmeal drink, and it can be flavored with chocolate or cooked fruit. If you're lucky enough to live near a market that caters to Mexican-Americans, you'll have no trouble finding the ingredients. The Mexican chocolate comes in discs individually wrapped in paper. It's already loaded with sugar and, depending on the brand, it's flavored with cinnamon, nutmeg, or crushed almonds. Be sure to look at the ingredients. Ibarra brand, which is imported from Guadalajara, is very pureâjust sugar, cocoa, almonds, cinnamon, and lecithin. Abuelita is another common brand. It's made in Mexico but distributed in the United States by Nestlé, so it's not hard to find. It melts well but lacks the flavor of almonds. What you decide to add to this recipe will depend on what's already in the chocolate you use.

In a blender, mix the corn flour and water until smooth (but see note, below). Transfer to a saucepan and bring to a boil, whisking constantly. Lower heat and simmer, for about 5 to 10 minutes, stirring to prevent lumps, until the mixture begins to thicken. Add the milk, raise the heat, and continuing to stir, bring the mixture almost to a boil. Lower the heat a little to prevent the milk from boiling, add the chocolate, and continue to whisk until all the chocolate is melted and the mixture is smooth. Simmer for 10 to 15 minutes more. The

atole

will be thick and creamy. Serve in mugs.

NOTE: Nowadays, many markets in Mexican-American neighborhoods sell “instant”

masa harina,

which eliminates the risk of lumps. If you can find it, you can skip the blender. Just mix up the corn flour with the water in your saucepan using a whisk.

Makes

2

generous servings

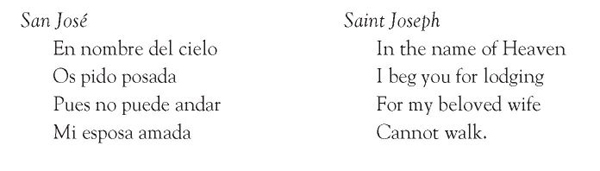

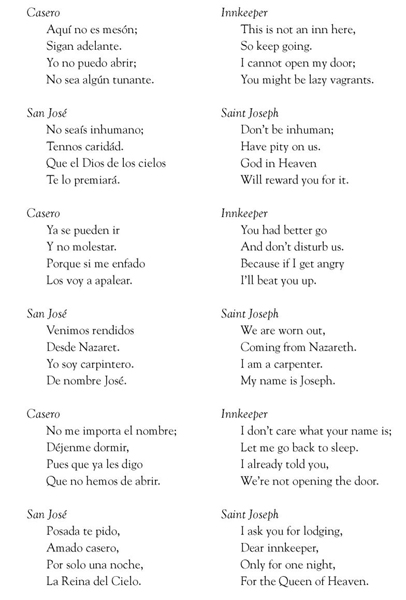

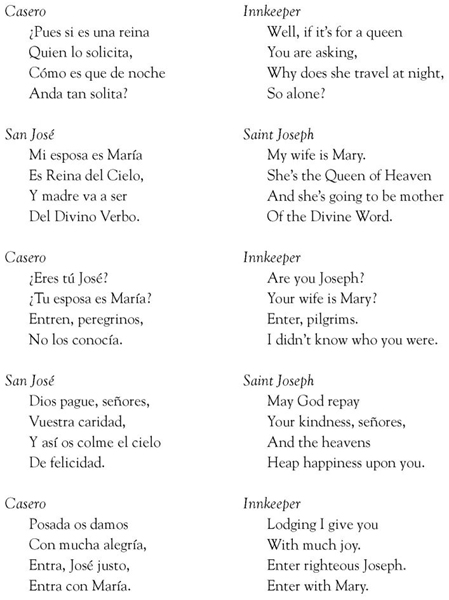

PEDIDA DE LA POSADA

Asking for Lodging

FOR NINE DAYS leading up to Christmas, the posadas are celebrated, re-enacting Joseph's search for an inn where Mary could give birth to the baby Jesus. There is a procession from house to house with candles and a manger scene, usually carried by children. Outside each house, the group sings Joseph's verses, begging for shelter, while inside, the host, who takes the part of the innkeeper, sings back his objections. When the door is opened at the end of the song, the group is invited in for refreshmentsâtamales, hot chocolate, and other treats. And there is often a piñata to break and sweets for the children.

Victor MartÃnez

Victor MartÃnez is a native Californian. He is the author

of

A Parrot in the Oven (HarperCollins), for which he received the 1996 National Book Award for

Young People's Fiction.

BARRIO HUMBUG!

AS A BOY, my Christmases were dreary reminders that my familyâno matter how colorfully one wants to paint itâwas poor. Until my father discovered the Lions' Club cheap-toy giveaway, what my brothers and I each got for Christmas was a rubber-banded bushel of dime-store socks and a pair of can't-bust-'em jeans to weather both winter and summer. Once, I got a plastic tyrannosaurus and, in the panic attack that followed, almost hyperventilated, believing God had definitely made a mistakeâtoys like that go only to rich kids!

Either way, my mother claimed we were lucky. In Mexico, she'd tell us, one doesn't expect a multigear bike, just some fruit and clay animals stuffed into one's shoes. Mexicans, she said, aren't soulless and corrupt like people in the United States, where there's so much to give away that we need two full-blown Christmases: one for the faithful minions of Jesus and another for those who just want to get drunk and receive gifts.

My mother was a wise woman, and still is, for that matter, but I was twenty-four by the time I figured out what she meant. That Christmas Eve, my sister Estela and I sat in our cousin's living room waiting for the twelve o'clock hand to turn. Around us, like wolves over the carcass of a deer, sat my cousin's children, breathless, waiting. My cousin wasn't wealthyâwhat Chicano family from Fresno, California, is? But he could, as they say, “rub the poor man's magic lamp” (which meant he could pinch pennies).

When the clock finally cranked twelve, a twister suddenly whirled into the room, snarling and licking at our hair. Actually, it was the kids, their little faces contorted with greedy enthusiasm, their chubby hands snatching at gifts as if they were afraid the toys would scurry away.

Kids barely out of their baby teeth became as predatory as great whites. The walls of the house practically collapsed from the frenzy of their feeding. My sister and I shivered with an icy fever from the cold greed. Those kids didn't just “open” their presents, they eviscerated them to judgeâin a calculating secondâwhat the hypereffluvia of their imaginations had been whipping up for months. Then they'd give off this low, almost caustic snort of disappointment. Obviously their gifts were not as phantasmagorically splendid as their fantasies. But then, maybe the next gift was! So immediately they gouged into another package.

There is a no more tortured landscape than the face a child makes when he hasn't gotten what he wanted for Christmas. Even this disappointment lasted only an instant, however. After gathering their own stash about them, they instantly decided what they really wanted was someone else's stash! That's when the fighting began, the sudden clap across the jaw, the stubborn pout, the grip on another's Tonka trucks, now undesired, now just weapons to be flung.

I stumbled away from my cousin's home a scorched man; I decided I'd never spin the wheel of Christmas commerce again. From that day on, I resolved, I would punch Santa on the nose (figuratively speaking, of course) whenever we crossed paths. I would remain unimpressed when my eyes happened to gaze upon a celestially baubled Christmas tree blazing magnificently at me from a department-store window. Any manner of rapture for this evergreen symbol, I believed, could only be purchased with a vacant heart, a heart that no longer listened to the howling, unexpressed agony of obliterated forests.

Furthermore, I felt free to explain to anyone who'd listen, we Chicanos were no better in this regard than anyone else. Corporate America had its hand buried to the elbows in our pockets. Ours was no innocent idyll of

posadas

and festive dinners. Here in America, I'd rant, we take as big a bite out of the earth's rump as the next glutton.

If you disagreed, I'd confront you with this: “Ask yourself how many times you've heard politically earnest Chicano parents say, âWell . . . the kids like it. It's for the kids.' And how many times have you seen the eyes of those same parents, who marched their dogs dead for equal rights, start twinkling on and off, red and green, when Christmas rolls around? We're as sentimental about this holiday as we are about El Movimiento. So every year,” I'd go on, “we shovel billions to corporations selling happiness inside a flame-red wrap. Why? Because we sense that, although we're responsible for them, our children don't really belong to us. They belong to the nightmare schools that educate them, to the fright-wig friends who influence them, to the pop-and schlock slot machine that passes for culture in this society!” I'd be very eloquent.

As you can probably imagine, riffs of moral umbrage of this sort didn't exactly endear me to family and friends, especially since I didn't have any children of my own. I became as welcome at family gatherings as a blistering rain on a papier-mâché parade, and despite the tradition that declares that hospitality cannot be refused without risking serious astral repercussions, people quit inviting me to Christmas dinners altogether.

Happily, one learns with ageâas I'm sure my mother, who had the wise soul of an ascetic Buddha, learned that no one wants a mealy bug in their geraniums. The gravity of my need to dematerialize myself wasn't as weighty as my need to be among people. After all, I came from a family of seven brothers and five sisters, and I wasn't used to being out in the cold. To be the Grinch at Christmas is to sled solo.

In the end, a little attitude adjustment served me well. As you may have guessed, I eventually succumbed to the glittering vortex of Christmas. I, who once touted my egalitarian cynicism to the stars, became a hypocritical wuss. And what of it? Christmas is a disease cured only by the death of one's fake enthusiasm for self-containment. If you want to know the truth, I like gleefully munching on cinnamon

buñuelos

and unabashedly drinking spiked eggnog under the mistletoe, andâcall me a wimpâbut I enjoy muddying my hands with

masa

every year for the customary tamales.

I'm not about to change back into that young, cynical spoiler who almost had his pessimistic butt driven from the family hearth. Because, at bottom, that is what Christmas is all about: family. For one day in a year that may have brought many disappointments, my family gets together and we talk, fight, relive past crimes inflicted on ourselves and others, and then we forgive. The world is out there, and we are in here; not alone, but together.