Las Christmas (7 page)

Pasteles

de Arroz y de

Gallina

RICE AND CHICKEN STEAMED IN PLANTAIN LEAVES

Making

pasteles

can be a community endeavor, like a quilting bee. As part of the holiday celebration, a group of women will get together to chop and prepare the ingredients. Then, sitting around the kitchen table, they wrap the

pasteles

like an assembly line, with one woman preparing the leaves, another stuffing them, a third wrapping, and a fourth tying the packets. The

pasteles

can be made weeks in advance and frozen to be cooked later. This recipe was contributed by Jaime Manrique's “aunt-in-law,” Jocabeth de Ardilo.

THE WRAPPERS

30 to 40 prepared plantain leaves, or cooking parchment and aluminum foil

Plantain leaves can be purchased either prepared or raw in markets where tropical produce is sold. To prepare raw leaves: Clean each leaf with a damp cloth. Using shears, cut each into 9- or 10-inch squares. Hold each leaf by the edges, with a pot holder or tongs, over a burner, turning constantly until the leaf begins to change color. Stack leaves and wrap in foil to keep warm. Leaves will get stiff and hard to work with as they cool.

The leaves impart a wonderful flavor to the stuffing inside the packets, but if you can't find them, you can substitute paper and foil. Cut cooking parchment into 6- to 8-inch squares. Then cut 8- to 10-inch squares of foil. For every plantain leaf, use a square of cooking parchment on a square of foil. Wrap so that the foil is on the outside. These little packets have to stand up to a long simmering process.

THE ACHIOTE

In a cast-iron or heavy skillet, heat ½ cup olive or vegetable oil. When very hot, add annatto seeds. Turn heat to low, continue cooking, stirring frequently, for approximately 5 minutes, until oil is a rich orange-red color. Allow to cool, then strain into a clean glass container. Set aside.

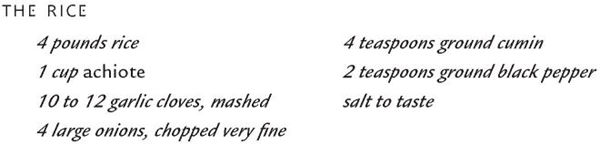

Wash the rice, drain well. In a big, heavy pot, heat the achiote oil until hot but not smoking. Add the garlic, chopped onions, and the rice. Cook, stirring constantly, until the rice becomes translucent. Add cumin, black pepper, and salt. Stir, then set aside.

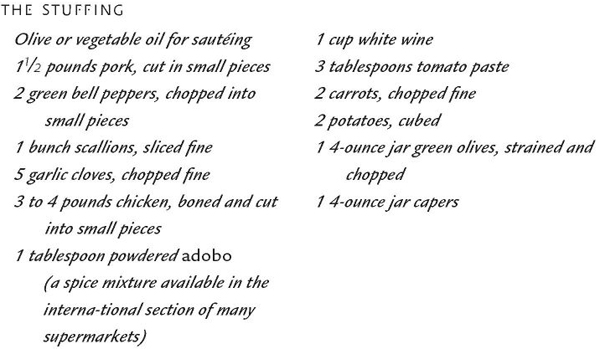

Oil the bottom of a heavy skillet, and sauté the pork for 5 minutes, stirring constantly so the meat cooks evenly. Then add the peppers, scallions, and garlic, cook for 2 minutes more, then add the chicken. Stir until the chicken begins to turn white, then add the other ingredients. Cook for about 10 to 15 minutes more. Vegetables will not be cooked completely at this point.

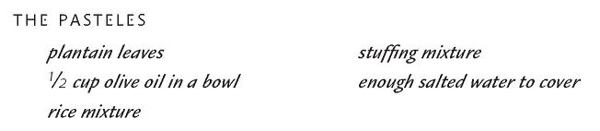

Lay a warm prepared plantain leaf flat on the table. Using a pastry brush, brush the center of one side lightly with olive oil. Place 2 heaping tablespoons of rice mixture in the center of the leaf. Top with 1 heaping tablespoon of stuffing mixture. Fold two long edges over the filling, then fold the open ends toward the center. Don't wrap too tightly, because the rice is going to expand. Cut about 1 yard of kitchen string and fold in half. Place folded string on the table with the loop facing you. Place the seam side of 2

pasteles

together. Put the 2

pasteles

in the middle of the string. Pull the ends of the string around the

pasteles

and through the loop. Pull the loose ends until the loop is in the middle of the

pastel.

Pull the two string ends in opposite directions towards the narrow ends of the

pasteles

. Turn

pasteles

over and tie the strings together in the middle.

Arrange

pasteles

on the bottom of large pot.

Pasteles

can be stacked three or four layers deep. Cover with salted water and bring to a boil. Lower heat and continue to simmer. After about 90 minutes, unwrap one of the

pasteles

and check for doneness. Serve in the packets. To eat, cut the twine, slide the stuffing out of the leaves, and enjoy!

Makes

30

to

40

pasteles

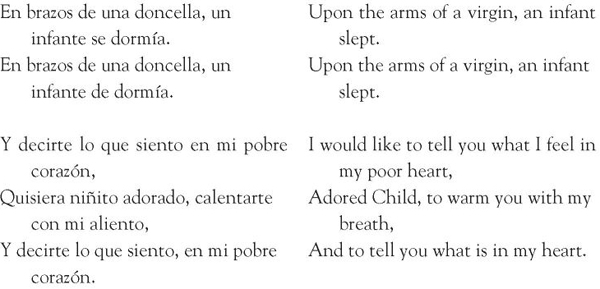

EN BRAZOS DE UNA DONCELLA

A Christmas Song from Ecuador

Michael Nava

Michael Nava grew up in Sacramento, California. He is the author of the Henry

RÃos mysteries, a detective series featuring a gay Chicano criminal defense lawyer.

His most recent book is

The Burning Plain

(Putnam).

CHARITY

I WAS RAISED on welfare. This was not so unusual in Gardenland, the Sacramento neighborhood where I grew up. It had always been a place where poor people lived. Most of us descended either from Mexican immigrants or Dustbowl Okies. My maternal family had lived there since the 1920s. My grandmother's family had been driven out of Mexico by the civil war that followed the Revolution of 1910. My grandfather was a Yaqui Indian, and his family had fled from Mexico to Arizona at the turn of the century to escape the invasion of their homeland in the Sonoran Desert by the federal army of Porfirio DÃaz. In Gardenland, they managed to achieve a modest, working-class affluence. My mother, however, their eldest daughter, did not fare as well.

Christmas was celebrated at my grandparents' house on Christmas Day, American-style, with a tree and a turkey dinner. Only my grandmother retained any connection to Mexican traditions and the only vestige of them were the tamales she served alongside the turkey. Among the piles of presents beneath the tree, there were always a few for my brothers and sisters and me, but these came from my grandparents or my aunts and uncles. My mother, scraping by on AFDC checks, could not afford presents, even for her own children, much less her nephews and nieces, which made Christmas a difficult time for her.

Then one year our family was chosen by the local chapter of the Lions' Club as one of the poor families whom the Club would sponsor at Christmas. This not only meant a basket of food would be delivered to our house on Christmas Eve, complete with our very own turkey, but also that we kids would be taken to a party at the Lions' clubhouse where Santa Claus would give each of us a present.

One of my aunts once told me that as a teenager my mother had been “as pretty as Rita Hayworth,” but by the time she was in her midthirties, with six kids and a husband in jail, her face had become a puddle of indistinct features held together by worry. But I was a kid and, except for the nickels I needed for candy and comic books, money meant nothing to me. Moreover, it was different being poor in the fifties and sixties than it is today, at least in Gardenland. Drugs and gangs had not yet entered the picture, nor were the poor despised as they are now, because poverty was still considered a circumstance that could be improved rather than a moral failing that could not. And Gardenland, as its name suggests, was a rural neighborhood where people grew some of their own food in vegetable gardens and old women, like my grandmother, kept flocks of chickens for eggs and meat. Moreoverâand this is the most important thingâGardenland was an isolated community, not so much on the wrong side of the tracks as a place the tracks never reached. We all lived the same way. There was nothing to which I could have compared us, that would have shown me how poor we were.

My mother, however, knew to the last penny how bad things were. She was the one who had to beg for extensions to pay the rent and for credit at the corner store. Poverty also forced her to forgo her pride and deliver her children to strangers who could give them things she could not, because this is a choice the poor must often faceâto keep their children in certain destitution or to give them away to the possibility of a better life. It was clear from an early age that I was a child fated to be given away. I was a curious, precocious boy who buried his head in books and looked far beyond the shantytown horizons of Gardenland. Throughout my childhood my mother gradually surrendered me to the world of white people, and it was there that I discovered how badly off we really were.

The Lions held their Christmas party in an auditorium in downtown Sacramento. I remember a big, brightly lit room furnished for the occasion with tables covered by red-and-green tablecloths, each with a centerpiece of gilded pinecones, holly, and candles. A long table at the back of the room held bowls of punch and plates of sweets. There were a couple of hundred children, most of us black or brown. We all wore our best clothes, enjoined not to get them dirty. There were always tears when someone scuffed her new shoes or spilled punch on his white shirt. We loaded paper plates with cookies, candies, and cake, and carried them, along with plastic glasses of punch, to our sponsor's table. The front of the room served as a stage from which we were entertained by a magician or a church choir singing the traditional carols, but they were merely a prelude. Behind them was an immense Christmas tree, its pine scent filling the room. Ropes of colored light twined through the dark branches hung with globes and tinsel. At the very top, almost scraping the ceiling, was a gold star bordered in tiny white lights. Beneath the tree were piles of presents gorgeously wrapped in silver and gold, red and green, and tied with bright ribbons and lavish bows. Next to them was a thronelike chair from which Santa Claus dispensed the bounty.

For most of us kids, the heaps of presents represented such unimaginable plenty that at first it hardly mattered what was inside them. But as the afternoon wore on and we filled ourselves with sugar, astonishment gave way to excitement, excitement to impatience, and impatience to anxiety that maybe there wouldn't be enough presents to go around. By the time Santa Claus emerged from the wings on a sleigh pushed by green-clad helper elves, the mood in the hall was not so much joy as agitation. It failed to occur to the good-hearted Lions, as they planned the party's little treats and surprises, that instead of delighting the poor children of Sacramento, the magician and the choir would only prolong our anxiety about the presents. We were kids who didn't have anything and to have these riches dangled in front of us was enough, really, to make us all a little crazy.

After a brief speech about how he had checked his list of good children and found our names on it, Santa distributed the presents with the help of an elf who handed him the packages from beneath the tree. After Santa read the name of the child for whom the gift was intended, he or she walked to the front of the room to accept it while a photographer memorialized the moment. With a couple of hundred kids, the ceremony took time and well before it was over any remaining gaiety had been replaced by restlessness. We were admonished not to open our presents until we got home, but some kids couldn't wait, and ripped through the shiny wrapping paper even as they walked back to their tables. Inevitably, they were disappointed because the present was not selected for the particular child but genericallyâdolls for girls, Lincoln Logs for boys, that kind of thing. At the end, the party felt no different to me than waiting in the hallway of the county hospital to have my eyes or teeth checked. But when I came home, and my mother asked me if I'd had a good time, I knew enough to tell her yes.

I was ten years old the last time I went to a Lions' Club Christmas party. By then I understood this was not a real party to which I had been invited because the hosts either knew or liked me. I had been asked only because we were poor, and I understood that one of the jobs of poor people is to be the object of charity. For whatever reason, out of some precocious sense of dignity or mere ingratitude, I did not wish to be one of the needy children on behalf of whom the Lions appealed to the public for toys. It was one thing to accept gifts from aunts and uncles who were better off than we were, because they were family and family provided for each other and there was no shame in it. Accepting charity from strangers was to be held up and labeled not just poorâbut inferior.

In a rare act of rebellion, I refused to go, but by then two of my siblings were old enough to be included, and my mother appealed to the good boy in me to take care of them. Mingled in that appeal was another, unspoken, plea: that I not judge her harshly for what she had to do to give something to her children they would not otherwise have. In that moment she made herself my equal, and I could not refuse her.

Our sponsor arrived. The three of us piled into his car, where a couple of other kids were already waiting, and we went off to the party. As soon as we entered the hall, I saw the tree and the presents and thought about having to make the march from our table to the front of the room to accept my generic gift. My stomach began to churn. Still obedient to my mother, I took my little brother and sister in hand and showed them the tree, the presents, and Santa's throne, and let them fill their little bellies with sweets. But their excitement only made me feel guilty, because I knew I had initiated them into something that was not quite what it seemed.

I sat worriedly through the afternoon, scarcely eating or drinking, waiting for the moment when my name would be called. At last, I heard Santa say, “Mike Nava.”

I slouched down in my seat.

“That's you,” my sponsor said.

“Mike Nava?” Santa repeated.

I looked down at my plate of half-eaten cake, refusing to meet my sponsor's eyes as he said, “Mike, go get your present.”

“No,” I whispered.

“Mike Nava?” Santa said, a little impatiently this time. “Where's Mike?”

The metal legs of my sponsor's chair squeaked against the linoleum as he stood up and strode decisively to the front of the room where he accepted my present from Santa, who joked that “Mike” seemed pretty big for his age.

“Here,” my sponsor said, handing me the gift. “What's wrong with you? Do you feel okay?”

“My stomach hurts,” I mumbled.

“Oh, why didn't you say so,” he replied. “You have to use the bathroom? The toilet?”

I nodded.

“You know where it is?”

“Yes,” I said.

I got up and made my way among the tables of clamoring kids to the bathroom, where I sat on the toilet, even though I didn't really have to go, until I thought enough time had passed for me to return to the party. I washed my hands at the sink, in case my sponsor checked, and stared at my face in the mirror. I was crying. I washed my face and went back for the rest of the party. When my sponsor dropped me off at home and my mother asked me if I'd had a good time, I tossed my unwrapped present aside and said, “Next time, I'm not going.”

She studied my face, looked sad, and replied, “I'm sorry you didn't have a good time,

m'hijo.

The kids will be old enough to go by themselves next year.”

The next day I scratched out my name on the tag of my still-unopened Lions' Club present and asked my mother if we could stop at the fire station on the way to my grandparents' house. I knew the firemen also collected presents for poor families. She pulled up and I ran in and shoved the gift into the hand of the first grown-up I saw.