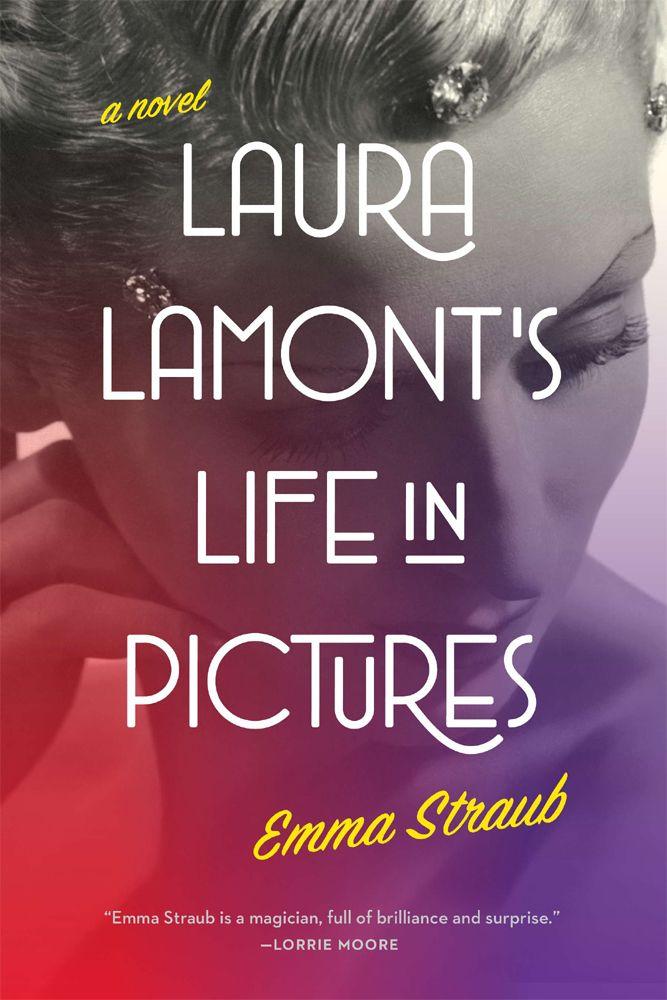

Laura Lamont's Life In Pictures

Read Laura Lamont's Life In Pictures Online

Authors: Emma Straub

LAURA LAMONT’S

Life in

PICTURES

A

LSO BY

E

MMA

S

TRAUB

Other People We Married

LAURA LAMONT’S

Life in

PICTURES

EMMA STRAUB

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

New York

2012

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA • Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario M4P 2Y3, Canada (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) • Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England • Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephen’s Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) • Penguin Group (Australia), 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) • Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi–110 017, India • Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) • Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

Copyright © 2012 by Emma Straub

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the author’s rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

Published simultaneously in Canada

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Straub, Emma.

Laura Lamont’s life in pictures / Emma Straub.

p. cm.

ISBN: 978-1-101-59689-0

1. Motion-picture actors and actresses—Fiction. 2. Fame—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3619.T74259L38 2012 2012011330

813’.6—dc23

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Book design by Michelle McMillian

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

ALWAYS LEARNING

PEARSON

FOR MY HUSBAND

,A GOLDEN STATUE

IF EVER THERE WAS ONE

You can take Hollywood for granted like I did, or you can dismiss it with the contempt we reserve for what we don’t understand. It can be understood too, but only dimly and in flashes.

—F. S

COTT

F

ITZGERALD

, The Last TycoonGold rushes aren’t what they used to be.

—D

AVID

T

HOMSON

, The Whole EquationI can be an actress or a woman, but I can’t be both.

—All About Eve

E

lsa was the youngest Emerson by ten years: the blondest, happiest accident. It was John, Elsa’s father, who was the most pleased by her company. His older daughters already wanted less to do with the Cherry County Playhouse, and it was nice to have Elsa skulking around backstage, her white-blond hair and tiny pink face always peeking out from behind the curtain. Elsa was a fixture, the theater’s mascot, and the summer crowds loved her.

The Cherry County Playhouse, so named because of the cherries Door County produced, was housed in a converted barn on the Emerson property in Door County, Wisconsin’s thumb. The barn was two hundred feet off the road, which had been renamed Cherry County Playhouse Road in honor of Elsa’s parents’ efforts and because there was no real reason not to. From May until September, tourists from Chicago and Milwaukee and sometimes even farther afield drove up and stayed in the small wooden rental cabins for the entire summer. After days spent on Lake Michigan or Green Bay, they would pile into the old barn and sit on wooden pews cushioned with calico pillows

sewn by Mary, Elsa’s mother. John directed and often starred, his booming baritone carrying into the surrounding trees, all the way to the road. The older girls, Hildy and Josephine, who had been such promising Ophelias and Juliets in their early teens, had instead taken jobs at the Tastee Custard Shack down the road and could most often be found handing over cones of frozen custard. Elsa was nine years old and happy to participate. She tore tickets, swept the stage of errant leaves and clods of dirt, and doted on the barn cat, who hated everyone, especially children.

The actors and crew members all moved onto the Emersons’ land for the entire summer. The boys from fancy schools on the East Coast, the ones with drama programs and crew teams, and all the delicate young women moved into the main house; the men with sturdier constitutions slept in tents and cabins scattered around the property, which gave the whole place the feeling of a summer camp. Elsa loved cuddling up to the beautiful young women, who would do her makeup and brush her hair for hours on end, all for the low cost of listening to them talk about their sordid and endlessly complicated relationships with men back home.

Hildy, Elsa’s second-oldest sister, was nineteen and had few interests outside of her own body. She would sometimes borrow her mother’s sewing machine to make new dresses, but would give up halfway through and leave the fabric limping off to one side like a wounded animal. Hildy was given to the dramatic, despite having forsaken the theater.

“Mother, I could not possibly help you with the dishes. My headache is the size of Lake Michigan,” Hildy said. It had previously been the size of the kitchen, the size of the house, and would soon be the size of the entire state of Wisconsin. Elsa sat underneath the long barn-wood table and watched Hildy waggle her knees back and forth.

“Excuse me,” Mary said. “There is no room for talk like that in this house.” Elsa could hear Mary’s tired hands shift to her hips, where they would roam around, pressing into the sore spots with her wide, blunt thumbs. Mary woke at dawn and made breakfast for the entire cast and crew—that summer, it was twenty-seven people, all of whom would groan loudly if given the chance. The girls’ mother ran a tight ship. Elsa often thought that her mother would have made an excellent homesteader, as she seemed happiest when conditions were tough and the going was hard.

Hildy rubbed her temples. She had always had headaches—all the Emerson women did, blackout, knock-down headaches that crowded the sides of their skulls and didn’t let go for days. One of Elsa’s chores was dampening a washcloth and placing it over her mother’s and sisters’ closed eyes, then tiptoeing out of the room. Elsa couldn’t wait to be a woman, to feel things so deeply that she too needed a dark room and total silence. She’d asked her sister about the headaches once, when she could expect them to start, and had been laughed out of the room.

“Honestly, Mother, honestly.” Hildy was the most beautiful of the three Emerson sisters, though Elsa was so young that she hardly counted. Josephine was the oldest and the most like their mother, with a wide, flat face that hardly ever registered any expression whatsoever. It was what their father called A Norwegian Face, which meant it had the look of a woman who had seen fifteen degrees below zero and still gone out to milk the cows. Josephine was inevitably going to marry a boy from one of the cherry farms down the road, and no one thought that they would be anything more or less than perfectly fine.

But Hildy was better than fine. Elsa loved to look at her sister, even when Hildy was having one of her episodes and her blond hair was wild and matted against one side of her head from all her flip-flopping

and thrashing in her sleep, and her pale pink skin had flushed and broken out into a crimson red. When she wanted to, Hildy could look like a movie star. It hadn’t come from their mother—that was a fact—neither the raw good looks nor the knowledge of what to do with them. Hildy pored over all the magazines she could find,

Nash’s

and

Photoplay

and

Ladies’ Companion

, and practiced putting on the actresses’ eyeliner in the mirror for hours every day until she got it right. When Hildy was feeling light, as she put it, and the headaches were gone, she wriggled through the house in castoff costumes, and Elsa thought she was as beautiful and lost as a landlocked mermaid.