Laura Marlin Mysteries 1: Dead Man's Cove eBook (17 page)

Read Laura Marlin Mysteries 1: Dead Man's Cove eBook Online

Authors: St John Lauren

BOOK: Laura Marlin Mysteries 1: Dead Man's Cove eBook

8.72Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

‘What?’ Laura took her hands away from her ears. ‘What do you mean they’ve left town? Where have they gone?’

She immediately thought about how Tariq, or someone with a voice just like his, had called her name on the empty street that morning. Maybe he’d come to say goodbye to her but had changed his mind at the last minute.

Mrs Crabtree put down her gardening shears and regarded Laura triumphantly. ‘That got your attention, didn’t it? Not so quick to dismiss me now.’

‘I’m sorry, Mrs Crabtree,’ said Laura, trying to prevent Skye from leaping at a seagull hovering above her neighbour’s garden. ‘I’ve had a horrible day at school and apart from that — ’

‘That’s Barbara Carson’s beast you have there, isn’t it?’ interrupted Mrs Crabtree. ‘It’ll be the wolf training classes you’ll be needing if he carries on at that rate. Not, mind you, that I’ll be complaining if he eats a seagull or ten. Nasty birds. I remember — ’

‘Please!’

implored Laura. ‘What did you mean about the Mukhtars? Have they gone on holiday or something?’ She pictured them on a cruise, with Mr Mukhtar hooking marlin out of the sea while Mrs Mukhtar sunbathed and Tariq, trussed up like a tailor’s shop dummy, sweltered in a suit.

implored Laura. ‘What did you mean about the Mukhtars? Have they gone on holiday or something?’ She pictured them on a cruise, with Mr Mukhtar hooking marlin out of the sea while Mrs Mukhtar sunbathed and Tariq, trussed up like a tailor’s shop dummy, sweltered in a suit.

Mrs Crabtree made a show of checking her watch. ‘I’m not sure I can stop to chat. I have my bridge club at six . . . Oh, if you insist I’ll tell you, but I must be brief.’

She reached out to pet Skye. ‘He’s quite beautiful, your husky, when he behaves himself, but he does need feeding up. He’s awfully thin. I think I have a spare bit of rump in the fridge.’

‘The Mukhtars?’ prompted Laura, ready to scream with impatience.

‘Gone for good, they have,’ announced Mrs Crabtree. She flung her arms up, like a conjurer unveiling a rabbit. ‘Gone in a puff of smoke. Sue Allbright saw a removal van pull up outside the grocery at around midday and next thing she knew Mr Mukhtar was boarding up the shop front. No more North Star. Such a shame. They always had the freshest produce.’

Laura was reeling. ‘But that’s impossible. I only saw Tariq this morning. He saved Skye from being hit by a car. I wasn’t very nice to him because I was still mad at him about something that happened a few weeks ago. Then Mrs Mukhtar came out and started yelling at him and he ran away down Fish Street. Did they find him? Did they take him with them?’

‘Well, they must have, mustn’t they? They’re hardly likely to abandon their own boy, are they? Not with him being the golden goose. Anyhow, Mrs Mukhtar told Sue Allbright that it was because of Tariq they were leaving. She said he’d been keeping some bad company in St Ives, and they were moving to get him away undesirable influences. I don’t suppose you know anything about that?’

Laura pretended not to hear the question. She knew very well that Mrs Mukhtar had been referring to her. She was the undesirable influence. ‘Where were they going? Did Mrs Mukhtar say?’

Mrs Crabtree consulted her watch and heaved herself off the wall, giving Skye a last pat. ‘Sue said Mrs Mukhtar wasn’t telling because she didn’t want any of these bad influences getting in touch with Tariq. If you ask me, that’s an excuse. I’m not one to gossip, but they were up to something, those Mukhtars. Sue is sure they’ve fallen into debt or are evading taxes, but I’d say it’s the tapestries that are the problem - the ones supposedly done by some famous Indian artist. Funny coincidence, but they only started appearing once Tariq came to live at the North Star. He came here once, did I tell you that? He wanted me to give you the little tiger. I was on my way out, so I gave it to Mrs Webb to pass along.’

Laura said in wonderment, ‘That was from him?’ Having it confirmed made her happy, but also greatly increased the guilt she felt for being horrible to him that morning.

Mrs Crabtree picked a couple of grass seeds off her mauve corduroy trousers. ‘Didn’t Mrs Webb tell you that?’

No, thought Laura. She didn’t. I wonder why.

‘At any rate, when he handed the tiger to me I noticed his hands were covered in cuts and scars. I had a blinding flash of inspiration and I said to him: “You made that tapestry, didn’t you? You’re the artist?” Well, you’d have thought I’d asked him if he’d stolen the crown jewels. He shook his head so hard it’s a wonder it didn’t fall off and bolted away like a frightened deer.’

All Laura could think was: So he did care.

‘If the Mukhtars have gone, you only have yourself to blame,’ Mrs Crabtree was saying. ‘They probably saw you as a threat to their investment. You were the girl most likely to destroy their golden goose.’

Whether it was because Laura was in shock or because no fires had been lit, number 28 Ocean View Terrace had a cold, shut-up feel when she returned. In the kitchen she discovered why. Mrs Webb hadn’t been in that day. The breakfast dishes were still on the table and no afternoon sandwiches or dinner had been prepared. The dirty clothes were heaped in the laundry basket where Laura had left them.

Laura tried to recall if her uncle had mentioned Mrs Webb having a day off, but nothing came to mind. In a way, she was relieved. She didn’t trust herself not to lose her temper with the housekeeper for tossing Tariq’s gift in the gutter. And Laura had no doubt Mrs Webb had done exactly that, probably hoping it would be swept away by the rain. Doubtless, she’d have told the Mukhtars about it too, possibly earning Tariq another beating. If it were up to Laura, she’d be fired on the spot.

Skye shoved Laura hard with his nose and lay down beside his food bowl looking forlorn. In spite of her mood, she couldn’t help laughing. She opened a can of dog food for him and boiled the kettle for a coffee she never made. Instead, she sat at the kitchen table deep in thought. So much had happened and she didn’t understand any of it.

If Mrs Crabtree was right and Tariq had been making some or all of the tapestries sold at the North Star Grocery when he should have been sleeping, doing schoolwork or having fun like other boys his age, it was nothing short of slavery. No wonder he’d always seemed so tired and thin. No wonder Mrs Mukhtar had been so concerned about his hands when he cut them falling off the ladder.

And now he’d been snatched away.

Somebody needed to help him, but who could she trust? The police wouldn’t believe her; Mrs Crabtree had a good heart but she was more than a little bit eccentric; and her uncle was leading a double life.

The clock chimed six, making her jump. The house was cloaked in twilight and so still she fancied she could hear the ghosts of past residents. Laura put on a jumper and turned on the lights. As they lit up the hallway, Skye rushed to the front door, hackles raised. He snuffled and growled at the crack. Then he threw his head back and howled. The sound sent chills through Laura.

‘Stop it, silly, it’s only my uncle,’ she said, grabbing the husky’s collar and dragging him away with difficulty. But no key grated in the lock. Heart beating, she peered through the letterbox, but could see no one.

She told herself off for her nerves. What did she have to be jittery about? After all, there was no proof that anything bad had happened. Tariq could be on holiday, Mrs Webb could be sick in bed with flu, J could be an ex-girlfriend of her uncle’s who had moved on very happily with her life, and Calvin Redfern could be a regular fisheries man, as he’d always claimed.

She was on her way to the kitchen to make a cheese sandwich when she noticed her uncle’s study door ajar. His laptop was sitting on his desk. After detention, Laura had stopped at the library to see if she could use the internet to investigate his background. The librarian had refused to let her in with Skye and Laura had refused to leave him out on the street. She’d left disappointed. It occurred to her now that she could do a quick search on Calvin Redfern’s computer. He’d told her to feel free to use it any time. Only thing was, he’d said to ask his permission first. Laura looked at her watch. Her uncle rarely came home before 7.30pm. An internet search took seconds. She’d be back in the kitchen long before then.

Before it was even a conscious thought, she was sitting in her uncle’s office chair. The computer hummed to life. Contrary to what she’d been expecting, it was no dinosaur model, but cutting-edge and powered by the latest technology. His files were laid out neatly and all were labelled with fish names.

Laura’s nerves had returned with a vengeance. She was so scared of what she might find, and also that Calvin Redfern might blow up if he came in to discover her toying with his computer, that it was hard to breathe. It didn’t help that Skye had disappeared. She called him, but he didn’t respond. With trembling fingers, she typed her uncle’s name into Bing and hit the Search button.

The

Daily Reporter

website was the first to come up. What Laura hadn’t anticipated was hundreds of other results - twelve whole pages of them to be exact. The

Daily Reporter

alone claimed to have forty two stories on him. She clicked on the most recent, dated a year earlier.

Daily Reporter

website was the first to come up. What Laura hadn’t anticipated was hundreds of other results - twelve whole pages of them to be exact. The

Daily Reporter

alone claimed to have forty two stories on him. She clicked on the most recent, dated a year earlier.

As she waited for the document to upload, Laura called Skye again. He didn’t appear. She drummed her fingers anxiously on the desk. Every passing minute increased the chances of her uncle walking in and catching her. On the screen, a banner newspaper headline was revealing itself slowly, letter by letter. It fanned out in a blaze of scarlet:

‘I’M RESPONSIBLE FOR THE DEATH OF MY WIFE’

Calvin Redfern in Shock Admission.

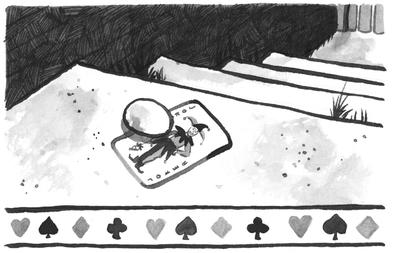

Beneath it was a grainy black and white picture of her uncle. He was smartly dressed but in a state of disarray. His tie was crooked, his jaw unshaven and his hair tousled and wild. He was shielding his face from the photographer but there was no doubt it was him.

The screen blurred before Laura’s eyes. A favourite warning of Matron’s came into her head: ‘Curiosity killed the cat.’

A floorboard creaked. Laura’s stomach gave a nauseous heave. Calvin Redfern was framed against the light from the hallway, Lottie by his side, just as he had been on the night she met him. He was a stranger at this moment as he had been then. The slope of his shoulders and bunched muscles in his forearms still spoke of a latent power, barely controlled.

‘So now you know,’ he said. ‘Now you know what sort of man I am.’

20

LAURA WALKED TO

the kitchen as if she was going to the gallows. Now that her worst fears had been realised, now that she was face to face with the truth about her uncle, she was no longer afraid of him, only of what would happen next. They sat down at the table as if they were an ordinary family preparing to eat a meal. The bread knife lay between them, beside the pepper grinder and the tomato sauce. Laura stifled an impulse to laugh hysterically.

the kitchen as if she was going to the gallows. Now that her worst fears had been realised, now that she was face to face with the truth about her uncle, she was no longer afraid of him, only of what would happen next. They sat down at the table as if they were an ordinary family preparing to eat a meal. The bread knife lay between them, beside the pepper grinder and the tomato sauce. Laura stifled an impulse to laugh hysterically.

‘So what sort of man are you? A murderer?’

There. It was out. She’d said it.

Calvin Redfern met her accusing gaze unflinchingly. The light fell on his face and there was no rage in it, only pain. ‘In some people’s eyes I am. In mine most of all.’

‘You killed your wife? You killed “J”?’

It was a guess, but she saw from his expression that she was correct.

‘Jacqueline was her name,’ Calvin Redfern said. ‘We were married for twenty years. I loved her more than anything in the world. I’d have faced down sharks, marauding elephants or run into burning buildings for her. But on the day that she needed me most, I wasn’t there for her. I could have saved her, but I was blinded by ambition. My work had become my obsession. By the time I came home, she was gone.’

Other books

Her Secret Agent Man by Cindy Dees

Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work by Paul Babiak, Robert D. Hare

El contador de arena by Gillian Bradshaw

Deception (Carrington Hill Investigations Book 1) by Allenton, Kate

Red Velvet Cupcake Murder by Joanne Fluke

Sweet Temptation by Maya Banks

The Living Will Envy The Dead by Nuttall, Christopher

The CEO's Accidental Bride by Barbara Dunlop

Star Brigade: Resurgent (Star Brigade Book 1) by C.C. Ekeke

Starry Nights by Daisy Whitney