Laura Shapiro (12 page)

Authors: Julia Child

Tags: #Cooks, #Methods, #Cooking, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #General, #United States, #Child; Julia, #Cooks - United States, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Women

“You are such a refreshing change from all the dainty cookery and gracious living that women are bombarded withâI hope you live to be a hundred and grow to enormous size.”

“Your honesty & forthrightness in all you do and say is greatly appreciated & welcomed in this age of phonyness & half-truths. We love you, Julia!”

“I love your T.V. program! You are the only person I have ever seen who takes a realistic approach to cooking.”

“Bernard Berenson wrote that there are two kinds of people, life-diminishing people and life-enhancing people. Certainly you must be the most life-enhancing person in America!”

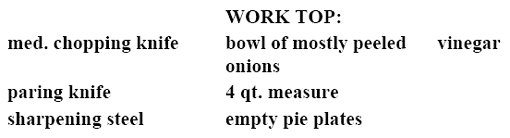

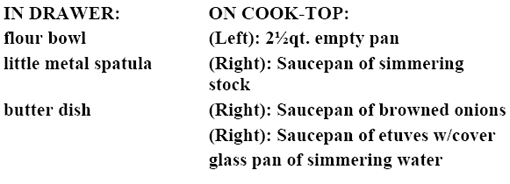

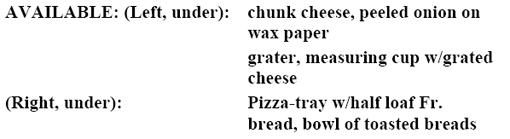

Julia once said that nineteen hours of preparation went into every half-hour show. First she broke down each recipe into segments, and then she did each step in her kitchen at home while Paul timed her with a stopwatch. How long did it take to chop a sample of onions for onion soup while describing how to hold and use a knife most efficiently, the way chefs did? How long did it take to start the onions cooking in butter and oil? To demonstrate browning the onions with sugar, salt, and flour? To blend stock into the onions and add wine? They worked on each step again and again, trying out different words and phrases, and different ways of showing a particular technique. Then they prepared a script, in the form of a detailed chart displaying time sequences, food, equipment, procedures, and what Julia would say. (Though she worked hard getting the wording as precise as possible, only the very beginning of the show was memorized; the rest she entrusted to adrenaline.) Every single item to be shown or mentionedâoven temperatures, pots of boiling water, samples of asparagus unpeeled and peeled and too scrawny to use, spice jars, spatulasâwas listed on the chart in order of discussion. Julia did all the necessary precooking, including a fully prepared version of the dish as well as various ingredients in different stages of readiness. Paul meanwhile created diagrams showing the TV kitchen from Julia's perspective as she faced the camera, with the location of every utensil and every morsel of food.

IN OVEN

: Casserole of gratinéed soup

Conditions in the TV kitchen were primitive: WGBH had burned to the ground two years before, and the new building wasn't finished yet. The first sixty-eight shows were staged in a donated display kitchen at the Cambridge Electric Company, where all the equipment had to be hauled in for rehearsals and taping, then hauled out again. On rehearsal day, Julia and Paul got up at 6:00 a.m. and packed their station wagon with precooked and partially cooked food, raw food, equipment and charts. They also tucked in any special items needed for a particular show, such as the thirty-square-inch chart of a beef carcass that Paul worked on one night until 2:00 a.m., drawing the bone structure and including all the classic cuts of beef. They discovered early on that it was easier to use the fire escape at the electric company than to load and unload the freight elevator, so the two of them carried everything up and set it out on long folding tables. Then Julia and the producer, Ruth Lockwood, rehearsed all day and into the evening, using what Julia called “live food” because that was the only way to get the timing and all the details correct. While they worked, Paul washed mountains of dishes. Then the Childs packed the car, went home, unpacked the car, Julia had a shot of bourbon and made dinner, and they went to bed.

On taping days, they did the same packing and hauling, and while Julia and Ruth were rehearsing, crew members began to arrive, lugging cameras and equipment up the fire escape. The studio became a mass of lights, cameras, and cables. The control center was in a trailer parked around the corner, where director Russ Morash sat watching two screens and issuing instructions to the cameramen. The crew worked out the lighting and camera angles, Julia was made up, and a microphone was hooked to the inside of her blouse, with a wire running down her left leg and into an electrical outlet. (By a miracle, she never tripped over this tether.) Finally, the floor manager shouted, “Sixty seconds! Quiet in the studio!” Julia looked into the camera, and taping began. Afterward, the crew devoured all the cooked food and took a break, while Paul washed dishes. Then the kitchen was set up with all different food and equipment, and a second show was taped. Bourbon and dinner followed.

The schedule was relentless, and despite the hours of rehearsal, those twenty-eight minutes were harrowing. One day the studio was so hot that after they completed the run-through, the butter was put into the refrigerator instead of being placed in the drawer where Julia was supposed to find it at the proper time. When the time came, she told Simca, “All I found was a little bowl with a paper in it saying âbutter.' So I had to say, âMerde alors, forgot the butter, always forget something,' and go practically off camera to the frig. And I pull out the butter carton and find to my horror it has only about 30 grams of butter in it. Luckily I was able to spot when one camera was off me and focusing on the chicken, and was able to mouth an anguished âBUTTER' to the floor manager, who snuck into the frig, with trembling fingers peeled paper off a piece of butter, and snuck it on the work table, with no camera spotting him.” The production team used to say they aged ten years with each show. But over the years, only a handful of shows had to be redone because of accidents or mistakes Julia couldn't fix on the spot. The second show, on onion soup, was one she couldn't save: she swept through the recipe so quickly that she arrived at the dining table with seven minutes to fill with chat instead of two. After that experience, they worked out a system of what they called “idiot cards”ânearly one a minute, tracking the time and reminding Julia what she was supposed to say and do.

ASPARAGUS

.

SET TIMER

.

HOW BUY, STORE

.

FRONT BURNER HOT

. (The camera she was supposed to be looking into some-times wore a small hat and a sign:

ME FRIEND

.) Later a second set of cards, orange instead of white, was introduced for emergencies. If Julia forgot an ingredient, or described a pot as “aluminum-covered steel” instead of “enamel-covered steel,” Ruth Lockwood would flash a special orange card alerting her to the error, and Julia would make the correction.

Six months into it, Julia was getting quite good, Paul reported to his brother. “Now she wipes the sweat off her face only when the close-up camera is concentrating briefly on the subsiding foam in the sauté-pan, for example. Her pacing is steady rather than rush-here and hold-there. She knows how to signal the Director that she's going to make a move out of range of the cameras, so they can follow, by saying, âNow I'm going to go to the oven to check-up on the soufflé'âinstead of suddenly darting out of the picture toward the oven.” WGBH continued to be overrun with letters from enchanted viewers. The

Boston Globe

published an editorial calling the show “the talk of New England” and signed up Julia as a regular columnist in the food pages. Kitchenware stores found they were running out of items Julia used on the showâflan rings one week, oval casseroles the next. “I can hardly go out of the house now without being accosted in the street,” Julia told Koshland in some amazement. New York, San Francisco, Sacramento, Philadelphia, Washington, and Pittsburgh all picked up the show, and floods of mail poured into every new station as soon as Julia appeared on-screen. Stories ran in

Time, Newsweek,

the

Saturday Evening Post,

and

TV Guide.

By January 1965, all ninety stations on the public television network were carrying

The French Chef,

and WGBH found it could raise money for the station every week by selling tickets to the taping sessions at $5 apiece. Paul greeted the audience before each session and asked them please not to laugh aloud during the show.

Julia spent most of the next forty years on televisionânew programs and repeats, public television and commercial TV, season-long series and one-time specials. She was a star, a host, a guest, a commentator, and a voice-over; once, to the delight of millions including herself, she was evoked by Dan Ackroyd on

Saturday Night Live

in a skit that became a classic. (Hacking away at a chicken, he fatally cut himself and collapsed, shrieking, “Save the liver!”) She grew old on camera: the energetic teacher who whipped up an entire beef Wellington in a half hour gave way over the years to an elderly woman who charmed the audience while letting guest chefs do most of the cooking. But her lasting image was established in the 1960s and 1970s by

The French Chef.

This was the Julia who won a permanent place in the nation's memory bank.

The self-consciousness that fluttered through the “Boeuf Bourguignon” show quickly disappeared with experience, but Julia retained a real-world quality that television couldn't tame. Even the food seemed to be a live, spontaneous participant. Julia welcomed it warmly and gave everything she had to the relationshipâparrying with the food, letting it surprise and delight her, very nearly bantering with it. Sometimes she lifted a cleaver and made a fine show of whacking the food to pieces, as if they had both agreed beforehand that the end happily justified the means. The day she made bouillabaisse, she placed a massive fish head on the counter and kept it there by her side, one great bulging eye staring out at the camera, while she prepared the stock. Every now and then she found a reason to pick up the gigantic head and fondle it. Tasting, of course, was a recurring event in each program, each taste a cameo moment treasured by the camera. Julia's whole countenance shut down as she lifted the spoon and focused inward, then she opened up again and, most often, looked pleased. “Mmm, that's good.” And if there was a chance to nibble, she unabashedly nibbled. After a painstaking demonstration of how to fold the egg whites into the chocolate batter for a

reine de Saba

cake, she held up the spatula and announced, “We have this little bit on the edge of the spatula which is for the cook.” Avidly, she licked up the raw batterâa treat as old as cake bakingâand added, “That's part of the recipe.”

Julia never said cooking was easy, but she said many times that anybody could learn it who wanted to. Viewers following her through the steps of a recipe could see for themselves how the consistency of a batter changed as the eggs were added, could watch the chocolate melting safely over a pan of hot water, could read the confidence in her motions as she snipped the gills off a sunfish with shears, or plunged a lobster headfirst into boiling water. Nothing was left unsaid, very little was relegated to instinct. Often she tossed in salt or spices without using a measuring spoon, but she always knew the exact amounts and mentioned them. “Here's what half a teaspoon of salt looks like,” she said once, and poured it into her hand to show people. She was teaching people to use their senses when they cooked, because she thought the senses belonged in every well-run kitchen, like good knives. There was no better instrument in the service of accuracy than an attentive cook who was watching and smelling and tasting. Monitoring the progress of a syrup for candied orange peel, she made a point of listening for the “boiling sound” coming from the mixture. You can use a thermometer here, she told viewers, “but I think it's a good thing to see and feel how it is.”