Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents (14 page)

Read Leaving India: My Family's Journey from Five Villages to Five Continents Online

Authors: Minal Hajratwala

His son, and then his son's children, would keep the restaurant open for twenty more years, serving up hundreds of thousands of beans bunnies. And the bunny chow itself would outlive apartheid, migrating to restaurants all over South Africa and then—as South African Indians migrated overseas—to Canada, England, and the World Wide Web.

Was the bunny chow a subversive response to repression? Or was it accommodation, compliance, opportunism? A cynic would say its Indian inventors were merely ensuring their profits; a loyalist might argue they did the best they could under trying circumstances, and that they too were just struggling to survive. And perhaps a poet would find it a potent metaphor for how the first generation of our diaspora views itself: essentially Indian at the core, packaged in and adapted to the local mores only as much as is conducive to economic survival. Without quite knowing it, however, this melding of tastes and textures becomes our lives—neither wholly "authentic" from the Indian perspective, nor fully assimilated from the vantage point of a white-bread culture, but a new creation in itself.

Long after Ganda's death, and a couple of years after the restaurant closed its doors—victim to a change of lease—the long, harsh day of apartheid came to a close. Overnight the revolutionaries became officials in charge of, among other things, writing a new history. And someone called cousin Raman.

A local-history museum was being erected, telling the stories of all the peoples of Durban. Would Raman contribute his family's items for the section on Grey Street? Your family was important, and you were on our side, he was told; and so he gathered photographs and memorabilia. Among his prized possessions was a letter from Nelson Mandela to the family member who owned a restaurant in Johannesburg, thanking him for providing a safe place for anti-apartheid leaders to meet. One of Ganda's grandsons, a photography hobbyist, contributed several images. Raman's father, grandfather, and several of his uncles were restaurateurs; he turned their papers over to the museum, which made them part of the permanent display. And so the businessmen of the Kapitan family were given a tiny piece of immortality.

Ganda's restaurant stood in a row of Indian businesses, any of which might have been chosen to represent the story of Grey Street. But history is never neutral, nor perhaps should it be. All histories are intimate, constructed by those with an interest in the stories they choose to tell—shaped, like bread, by the human hand.

At the southernmost tip of Africa, a lighthouse rises from the shoals where two oceans meet. I have clambered among the rocks and sand, waded into the waves. One sea is browner, the other bluer, and it is not a trick of the light.

To the west, the cool Atlantic swells up toward London, New York, and South Africa's most picturesque city, Cape Town. To the east, the Indian Ocean is several degrees warmer; it gives the coast of Africa from Durban to Mombasa a tropical climate profitable for sugar and tourism, almost homelike for the more than a million Indians who have lived there for generations. This confluence of oceans is a rare coincidence of political and natural geography, where the act of naming does not create an arbitrary border, but gives voice to a natural one.

And yet it is the most fluid, the most porous of borders. East and west meet with a great force, a terrible frothing and crashing of waves. The whitecaps swirl, and as much as one tries to follow a dark wave, it curls under a paler one from the other side; as far as I can track a blue wave, it does not, of course, hold. Like the several great civilizations that have clashed and coexisted in southern Africa over the last two centuries, the waters cannot be segregated.

And who can tell which wave is resisting, which collaborating? The sea reveals no moral; what moves the whole is a greater tide. Perhaps the currents of history are what they are, and we only choose—or think we choose—which side to view them from, and where to take a stand.

4. Salt1945

Estimated size of the Indian diaspora: 1,157,728

Countries with more than 10,000 people of Indian origin: 101. Mauritius

2. South Africa

3. Trinidad and Tobago

4. British Guiana

5. Fiji

6. Kenya

7. Tanganyika

8. Uganda

9. Jamaica

10. Zanzibar

Instead of a common riot confined to one class of persons it was of the nature of a wide spread insurrection.

—Account of the salt-tax riots of 1844, Surat, India

M

Y MOTHER'S FAMILY

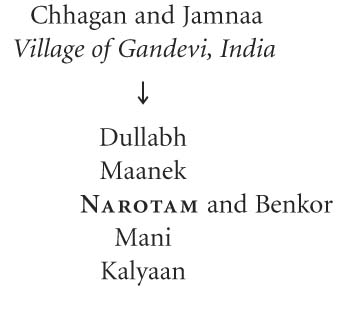

is considered "small," meaning that it has had a scarcity of sons. Unlike my father's family tree, which branches again and again—seven sons, five sons—my mother's family tree is a straighter line: only a few boys per generation. From this slim history, her father, Narotam, emerged.

The only grandparent I remember was my Aaji, his widow. We met for the first time when I was seven, shy and reeling from the shock of migration. My family had just moved from New Zealand, the only home I remembered, back to the United States. After stops in Fiji to visit too many relatives (my only memory is of a fish bone getting painfully stuck in my foot) and in California, we landed in Iowa to visit my mother's brother and his family. He had brought Aaji to live with him a few years earlier. When I was enjoined to hug her, I obeyed—and promptly broke into tears, at the strangeness of it all.

From then on we saw her once or twice a year in Iowa. I learned to embrace her without sobbing, leaning into the softness of her sari and comfortable rolls of fat. But the combination of infrequent visits, strange old-lady smells, and the fact that she could never seem to pronounce my name correctly kept us strangers. I was distracted too, I suppose, by her odd habits. She sniffed something from a small tin that she kept hidden in her bosom, and when I asked my mother what it was, she said

tamkhil

—tobacco. I had never heard of snuff before, and filed this away in my mental folder of things old Indian ladies do. She was quiet, never saying much except to moan

Raam, Raam,

invoking the name of the Hindu god-king whenever she had to stand up or sit down, arthritic knees creaking. She drank, before dinner and sometimes before lunch, a shot of whiskey mixed with water, chased by a Guinness. My parents being teetotalers, I found this alarming as well. It never occurred to me to ask her about history—not even about my grandfather, my Aajaa.

Aajaa.

The word feels strange in my mouth, for I never had occasion to use it, missing him by six years and two continents. Growing up in New Zealand and then Michigan, away from other relatives, I knew little about Narotam Chhagan: that he died when my mother was still in school; that his death and the collapse of the family business left my mother and grandmother very poor; that he had met the prince of Tonga; and that he and his friends drank so much that my mother fled the house on weekends, seeking a few hours' respite at double-feature matinees, which is why even today she hates alcohol and adores Burt Reynolds.

When I was eleven years old, it was a movie that showed me another side of my Aajaa's life: Richard Attenborough's

Gandhi.

Today, I can critique the film for its historical distortions and Hollywood lens. But back in 1982, in suburban Michigan, it was a precious opportunity to see India and Indians on the big screen.

First, however, we had to find a screen. In the conservative, middle-class suburb of Detroit where we lived,

Gandhi

was not a big release. The town's sole movie house, the Penn Theater, was an old-fashioned hall with red plush seats that showed such classics as

Casablanca

and

Gone with the Wind.

My family never went there, opting instead for James Bond flicks and

E.T.

at the sixplex in a nearby suburb's mall. I did not see the Hollywood classics until years later, in a university class on the history of film. By then, in the 1990s, the Penn Theater had changed; an enterprising Indo-American was renting the theater on Saturday mornings, showing Bombay musicals to packed houses, selling samosas and chai along with popcorn at the concession stand.

But during my childhood, the Indian community in Michigan was still tiny, so we had to drive half an hour to the progressive university town of Ann Arbor to see

Gandhi.

It was screened in one of the university's auditoriums. We sat near the front, next to the center aisle, craning our necks throughout the three-hour epic.

Halfway through, a pivotal scene occurs. Gandhi's followers have marched to the sea to protest a tax on salt. As they approach the saltworks, a row of police armed with

lathis—

five-foot clubs tipped with steel—stand ready to stop them. Gandhi's men, though, keep walking. When they are just a few inches away, the police officers strike: heads crack, faces split, ribs are smashed.

But more men take their place, row after row advancing—peacefully, calmly, with determination but not violence. And as the police keep beating them down, the camera dissolves to "Walker," an American reporter played by Martin Sheen. He is at the phone, calling in his story. From the script:

"They walked, with heads up, without music, or cheering, or any hope of escape from injury or death." (His voice is taut, harshly professional.) "It went on and on and on. Women carried the wounded bodies from the ditch until they dropped from exhaustion. But still it went on...

"Whatever moral ascendance the West held was lost today. India is free, for she has taken all that steel and cruelty can give, and she has neither cringed nor retreated."

(On Walker close. His sweating, blood- and dirt-stained face near tears.) "In the words of his followers, 'Long live Mahatma Gandhi.'"

Then the word I

NTERMISSION

filled the screen, and the lights went on in the Ann Arbor auditorium, and my mother turned to me in the light and said with some surprise, "You're crying."

After a moment she added, quietly, "You know, my dad was in that march."

According to his first passport, now yellowed and crumbling, Narotam was born in the village of Gandevi, Surat District, in 1908. A later passport gives a birth date, December 12, which he must have invented for a government bureaucrat. In a village where the passing of time is measured by religious festivals and natural or personal disasters, where birthday celebrations are reserved for the incarnations of the gods on earth, no one would have memorialized the exact moment of arrival of the second son of a family so humble they were known as the Chaliawalas, people of the sparrow.

Against the blur of history, one episode of my grandfather's life stands out in sharp relief. Luckily, a photograph was taken at precisely this moment. He stands young, intense, dressed like a saint all in white. The way the silver has faded over seven decades creates a halo around his body, a pale, pure cocoon of light. It is July 1930, and he has emerged from three months of hard labor in prison, for joining Gandhi's nonviolent revolution.

In front of a backdrop painted to look like a courtyard, my grandfather's robes beam purity and defiance:

khaadi

cotton, not from Great Britain's mills but made in India, in the villages, on the spinning wheels of revolution. It might have been my grandmother who wove the spun thread into three yards of cloth for him on a rickety hand loom.

Gandhi predicted the simple wooden spinning wheel would overturn the British Raj.

Chakra:

the word is the same as for the mythical wheels of fire deployed by the Hindu gods in battle. And in what became the world's greatest nonviolent war, the domestic version proved a powerful weapon, sending the flames of revolution into every household, every hut.

For India's poor, spinning made not only political but also economic sense, freeing them from the expense of foreign cloth and offering a dignified means of making a living. For the wealthy, the rough, homespun saris and dhotis became a symbol of what today we might call, with the cynicism of our age, political correctness.

But for Gandhi's true believers, there was no cynicism. Many were not political or urban elites but villagers from humble families and of even humbler means. In that era of great hope and great uncertainty, some dreamed of new possibilities, others cowered in fear, and a handful put their bodies on the line. Their general was a slim, soft-spoken man in a loincloth, and one of his foot soldiers was my Aajaa.

For at least four thousand years, Hindus of the "upper" castes have divided human life into four stages: student, householder, retiree, renunciate. In trying to write about my Aajaa's life, I am reminded again of how little I know about most of my ancestors; how little anybody knows. They were peasants, after all, the details of their lives sketchy from the very beginning. But Narotam would have known about these phases, and hoped his life would follow the ideal pattern of millennia.