Legends and Lore of the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast (13 page)

Read Legends and Lore of the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast Online

Authors: Edmond Boudreaux Jr.

The cannon was supposedly captured at Spanish Pensacola on November 7, 1814. Since it was possibly a naval cannon, it would have been converted for a land battle by securing it to a wagon-style gun carriage. Of course, the need for all the fire power they could muster would have made any portable piece or any that could be made portable attractive for the defending of New Orleans. We do know that after the victory at Pensacola, Jackson received information that a large British invasion fleet had departed Jamaica and was headed to New Orleans. Jackson had to take his large force and equipment and move quickly if he was to engage the British before they reached New Orleans. He would also have to build a defense to prevent the British from having easy access from the shore to the city. The effective defense of New Orleans and the effective defeat of superior British forces secured Andrew Jackson's position in the White House. It also announced to the world that the United States could and would defend itself.

With this in mind, time would have been of the utmost importance to the troops, and the difficulty to obtain parts and equipment to repair the axle may have factored into their decisions about the cannon. If said cannon carriage axle broke, it would have been abandoned. It is possible that Jackson's men had converted it to a wagon-style gun carriage. One cannot exclude the possibility of Spanish conversion of the carriage. This version may be more feasible since the carriage would have been about thirty-three years old. It also would have remained in Pensacola and not moved during this time. Mr. Worcester's story indicates that his “great-grandfather appropriated” the wheels. I love the use of “appropriated” here to describe procuring something; it sounds so much better than “stole.” Supposedly, the cannon would lie where it was discarded for almost a century and a half. That is, until 1957, when it was transported by Mr. J.T. Worcester from Fairhope, Alabama, to the Old Spanish Fort, today's La PointeâKrebs House. It was mounted on a special-made carriage that was positioned to face Krebs Lake.

This British four-pounder has played a unique part in our Gulf Coast history, beginning with the British Period of 1763 to 1781, the Spanish Period in 1781, the War of 1812 and General Andrew Jackson in 1814. La PointeâKrebs House and its cannons are not only Mississippi's Golden Gulf Coast treasures but national treasures as well.

CHAPTER 19

T

HE

M

ONTE

C

ARLO OF THE

S

OUTH

Long before the arrival of the casinos in 1992, gambling existed along the Mississippi Golden Gulf Coast. One of the legends was that Pradat's Green Oaks Hotel offered gambling as one of its main attractions. Biloxian captain Ernest Desporte was the one who deemed Pradats the “Monte Carlo of the South.” Captain Desporte's memories are located in the Historical Wing of the Biloxi Library. During his lifetime, he published articles under the “History Corner” and “The Old Timer.”

Of course, one of these stories was about Pradat's gambling establishment. Pierre Pradat and his wife, Elizabeth Ixelin, owned the Green Oaks Hotel. The hotel was located on the property east of Tullis-Toledano Manor, where the Boys and Girls Club was located before Hurricane Katrina. Katrina would destroy both the Tullis-Toledano Manor and the Boys and Girls Club. As far as the Green Oaks Hotel, advertisements in New Orleans papers indicated that the establishment offered a barroom, billiard table, yachting, swimming, horseback riding, a bathhouse and more.

In describing the many amenities of the hotel, one thing was not explained: was the story of gambling a legend or fact? We do know that Pierre and Elizabeth were married in New Orleans. While in New Orleans, Pierre Pradat was granted a gambling license in 1833. At that time, it was not illegal to gamble in Mississippi or Louisiana. Along the Mississippi Gulf Coast, gambling was most likely offered at all the “watering holes,” as the hotels were called. In fact, one could say gambling was considered an honorable profession during this period.

The “Monte Carlo of the South.”

Edmond Boudreaux

.

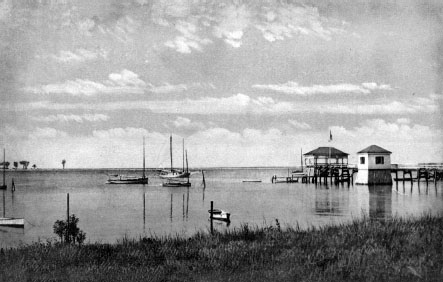

Biloxi beach with Deer Island in the background, near Pradat's Green Oaks Hotel, 1906.

Courtesy of Alan Santa Cruz Collection

.

It appears that the Pradats' Green Oaks Hotel offered an up-to-date gambling resort, in addition to other services. The fact that the Pradats were considered part of Biloxi's social society indicates a successful business. Pierre died in 1854, and Elizabeth followed between 1853 and 1856. Their sons, John and Eugene, would continue to run the Green Oaks Hotel. During the Civil War, it was reported that even Union officers from Ship Island visited the Pradats' gambling resort. Sometime before 1900, its doors closed.

We do have to remember that during this period, lotteries and horse races were common, everyday events. In fact, if we look at our colonial history, we will find many examples of games of chance. In the journal of Father Paul Du Ru, a missionary priest with d'Iberville, he observed that the Indians loved to gamble. “One has no sooner given a present than he finds it in the middle of the square staked in a ball game. It is astonishing how calmly they gamble. Apparently winning or losing is alike to them.”

Of course, the Europeans were also fond of a game of chance. Soldiers have been gambling as far back as the Roman and Greek times. The same was true of the French Colonial soldiers in Louisiana who played cards and dice games. We can thank the French for the suits in decks of cards, like hearts, diamonds, clubs and spades. Although the casino gaming industry first arrived in 1992, games of chance will always remain a part of Mississippi's Golden Gulf Coast history.

CHAPTER 20

S

HOO

F

LY

At one time or another while growing up, I think we have all sung or heard the song “Shoo Fly, Don't Bother Me.” The song “Shoo Fly” has been around since 1869, but the other popular Shoo Flys along Mississippi's Golden Gulf Coast were wrapped around trees. Located along the shoreline were many of these picturesque raised platforms that wrapped around majestic oak trees. Some were square while others were octagonal in shape.

The Shoo Flys had staircases that ascended to about ten- to twelve-foot platforms with benches that lined the raised rails. The platforms wrapped around the trees and afforded the people an excellent view of the Mississippi Sound.

Before Camille, one famous Shoo Fly stood on East Beach in Biloxi. I say “famous” because tourists and locals alike would stop, take pictures and view the unusual structure. This Shoo Fly was built before 1896 and stood in front of the residence of Mrs. Hunt Henderson of New Orleans. Many of the stately homes that lined the waterfront were owned by New Orleans residents and used as summer homes. This Shoo Fly platform was about ten feet high and about twelve feet in diameter. Unfortunately, Hurricane Camille destroyed it in 1969.

Supposedly, the Shoo Fly enabled the residents to enjoy Gulf breezes without being pestered by deer flies or other pests; thus the name Shoo Fly. Did it work? Most folks along the Golden Gulf Coast know that a good stiff breeze will help, but if there's no breeze, you're in trouble.

The most photographed shoo fly in Biloxi, late 1800s.

Courtesy of Alan Santa Cruz Collection

.

Ray Thompson, in his “Know Your Coast” series, wrote two articles in May 1956 about the Shoo Fly. In the first article, he asked for information on how this structure got its name. While he received many replies, in the second article he used the responses of Mrs. John Leonard and Mrs. Rita Fayard Dildy of Biloxi to offer what he called “excellent explanations.” While both seem to contain a little truth with a dose of legend, they make good stories.

Mrs. Leonard explained the deer fly problem along the coast and said, “People sort of muttered the expression automatically when they swatted at one.” She compared the breeze in the Shoo Fly to the breeze created by ceiling fans. The fans she alludes to were not electric fans but rather were operated by servants. This was usually during meals in upper-class homes to keep flies off the prepared food.

Mrs. Fayard said, “âShoo' itself was a favorite and frequent word with old-time French housewives on the Coast.” She explained that the women, with brooms in hand, would chase the chickens from their gardens, saying, “Shoo, Shoo, Poulet!” or they would similarly chase their children out from underfoot by saying, “Shoo, Shoo, Petite!” In

A Dictionary of the Cajun Language

, by Reverend Monsignor Jules Daigle, “shoo” is defined as “to chase away.” One way or another, the Shoo Fly became a part of Mississippi's Golden Gulf Coast history. Fortunately, today there is a reproduction of a Shoo Fly on Biloxi's Town Green to help us step back in time.

CHAPTER 21

G

EORGE

E. O

HR

The Mad Potter of Biloxi

George Ohr was born in Biloxi on July 12, 1857, to George Ohr Sr. and Johanna Weidman. George Ohr Sr. opened a blacksmith shop, and his wife operated a grocery store. George E. Ohr Jr. married Josephine Gehring on September 15, 1886. He grew up in Biloxi with his family, and he had an overly active boyhood, which caused him to be in hot water most of the time. About 1874, George E. Ohr Jr. headed to New Orleans, and for several years, he tried many different fields of work, even the family trade of blacksmithing, before returning to Biloxi. In 1879, a friend of the family, Joseph Fortune Meyers, took him on as an apprentice in his New Orleans pottery. It would be here that he fell in love with the art of pottery-making, and Joseph Meyer became his mentor. In 1883, George E. Ohr Jr. returned to Biloxi and, about 1885, opened his own pottery. In 1887, two Massachusetts brothers helped with the establishment of the Newcomb Art School in New Orleans. In 1896, Ellsworth and William Woodward hired Joseph Meyer to build the kiln and operate it for the art school at Newcomb College for Women. Meyer, in turn, hired George E. Ohr Jr. as an assistant. George E. Ohr Jr. divided his time between his Biloxi Pottery and Newcomb, but after a few years he was released from employment and returned to Biloxi.

By the late 1800s, George E. Ohr Jr. was a well-established potter operating his Biloxi Pottery. On November 7, 1891 the

Biloxi Herald

reprinted an interesting article from the

New Orleans Item

newspaper referring to George Ohr as the skillful art potter of Biloxi who had visited their offices with a “cunning handiwork in the shape of a puzzle cup [mug].” The writer described it as “mug-shaped and containing a number of holes and secret passages with outlets at unexpected places.” Of course, he explains that the puzzle is to put as much liquid as possible in the cup, and the trick is to drink from the mug without spilling a drop “down one's shirt front.” The writer indicated that Mr. Ohr had written in his own words, “The last drop may be drunk from the puzzle or trick cup without spilling a drop.” The reporter declined to make any attempt, feeling it would result in “a bath.” He would prefer to experiment in private.