LEGO (21 page)

Authors: Jonathan Bender

My thoughts about the museum and its founder are interrupted momentarily. “Do you know when the food truck is getting here?” a woman asks me.

“I think the local fire department is coming; but they’re a bit late,” I tell her, realizing that there are a lot of community people participating in the convention. It’s not just adult fans who want to see this weekend succeed. As a result, Brick Show has the same vibe as a fair or a block party where local people are chatting about life as much as about the LEGO creations.

Later I help this woman’s son figure out how to connect two houses with an arched LEGO piece. “You must be a great builder, you’re great with kids,” she says.

Is this single mother flirting with me? Wait, she called me a great builder.

The building compliment is a bigger ego boost than her overly friendly tone. But I’m brought back to earth quickly. Another mother is asking me something from the front of the room.

Is this single mother flirting with me? Wait, she called me a great builder.

The building compliment is a bigger ego boost than her overly friendly tone. But I’m brought back to earth quickly. Another mother is asking me something from the front of the room.

“Can you help my daughter find a horse? She can’t find a horse anywhere.” In the piles of jumbled brick, it’s difficult to find a specific piece, but I discover that I’m able to remember where I’ve seen various parts from earlier in the day. I squat down next to a storage tub that a brown-haired boy in a Yankees T-shirt is riffling through. He holds his hand up in victory—he finds the horse before I do, but he needs it for his creation. So I don’t have a horse for the little girl.

Feeling confident, I decide to build her a horse myself. After all, this is LEGO, it’s supposed to be turned into something else. A few minutes later, I hand the mother a creation made from tan slopes and brown bricks.

“Oh, what’s this?” she asks.

“It’s a horse,” I respond.

“Oh,” she says uncertainly. “Of course it is. Thank you, that was very nice.”

I find a reason to explore the museum soon after, because I feel my face growing flushed. I have made the little girl a camel—a cousin to the camel that sits on the bookshelf in my living room—definitely not a horse. Although it has been said that a camel is merely a horse made by committee, I have no idea how history will judge a lone man who continually issues faulty horse designs. It seems my LEGO animal skills are not that far along after all.

The camel incident aside, I find myself enjoying the day. I spent three summers of my college career as a camp counselor, and this is proving to be not that different. When each kid has finished working on their baseplate, I ask them to tell me the story of what is happening: “a robot attacking an alien,” “a monster trapped inside the castle wall,” and “bad guys fighting good guys.” The castle theme has been dwarfed by the children’s imaginations.

I hear my knees pop later that night as I sit down across from Brian Korte, the convention’s first day having drawn to a close. A few adult fans are gathered around a foldable dining table with attached benches—the kind found in every school cafeteria when I was growing up. We’re all eating pizza that Dan bought, with the exception of Brian, who is busy putting together panels for a dragon mosaic.

“Dan, last night I was pretty freaked out when I was walking out of the LEGO Crack House with a bag of grass,” says an adult fan wearing a New York Mets baseball cap.

I look up sharply, wondering if I have missed a double meaning in the nickname for the second school building. But the man is smiling as he points to a ziplock bag filled with LEGO grass elements.

I laugh, and Brian smiles back, but he’s got headphones in, so he hasn’t heard the joke. His brown hair is as neatly parted as the brick piles he has sorted in order to finish the light blue patterned layout—the background of the dragon mosaic he’s building during this year’s convention. I ask Brian what drew him to mosaics.

“I enjoy this style of art, it’s making something that is bigger than the sum of its parts,” he says, sliding off his headphones and running his palm across the bridge of his nose.

Brian, thirty, is not alone. Mosaics are a growing category for LEGO builders because the cost is predictable, the design is scalable, and custom software exists to help turn photographs into pixelated mosaics. Besides color, the main variations among mosaics concern the orientation of the bricks: they can be either studs-up or studs-out. It’s easiest to think of those terms by how you view the model. With studs out, you would see and feel the bumpy studs if you touched the mosaic. Studs up, you see the sides of the LEGO bricks, allowing for more detail; and you can use either plates (one-third the height of bricks) or bricks. But using more bricks increases your expense, and studs-up mosaics usually need to be glued to keep the pieces together.

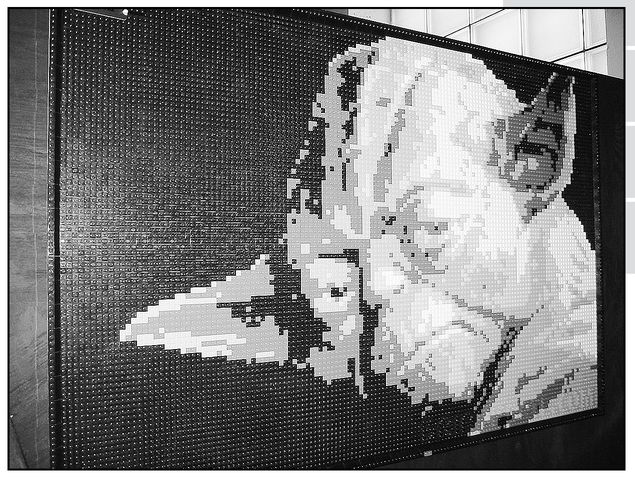

In 2004, Brian was a Web designer looking for a unique wedding present for two friends. Relying on his experience as a crossstitcher, he designed and built a gray-scale LEGO mosaic of the couple. The response convinced him that there might be a business in building custom mosaics. He launched Brickworkz that year in Richmond, Virginia. Portraits of couples turned into corporate commissions. A mosaic of Yoda he built during that time now hangs here in the museum, in the Space Room.

“They’re expensive and tedious, but they’re worthwhile,” says Brian. “But I don’t glue them; otherwise, I could have never turned my ex-girlfriend’s head into Yoda.”

Brian came to Brick Show in 2007 to design and help build the image that garnered the museum a Guinness World Record. He brought with him 525 pages of instructions, which had taken him more than a month to map out. Together with Dan and his staff, Brian built for thirty-six hours to complete the outline of the semitrailer, a minifig sun, and landscape. The children who came to the convention then put together their own baseplates to fill in the trailer of the truck.

Brian still has a few hundred 1 × Is to snap in place before stopping for the night, but I head back to the Super 8 motel in Zanesville, Ohio.

It’s early Sunday morning when I walk up to the back door of the museum and find Breann and Tom outside, sipping coffee, waiting for Dan to come unlock the building. I take a seat on the stone steps, my back achy from squatting beside kids the day before.

“This is really adult fan heaven,” says Tom. “It’s just an amazing collection of LEGO.”

“I know, it feels strange, like the townspeople are living in the same town as Charlie and Willy Wonka—only they have no idea that Willy Wonka’s factory is all that special,” I reply.

And yet, that’s the strangest part of the Toy and Plastic Brick Museum. The town of Bellaire doesn’t understand the financial and sentimental value of the collection inside the former school. But adult fans don’t get what Dan is doing either—they don’t trust that he is willing to share. This is in part because adult fans’ collections are so personal. It’s rare that anyone gets to see where someone else builds, because showing off a work in progress opens you up to criticism. The idea that someone would have an entire museum constantly in progress is unfathomable. So adult fans hang back to wait and see if Dan will succeed, preferring to spend their money traveling to established conventions or to LEGOLAND.

Dan arrives slightly out of breath, flips open the door, and announces that he’s headed to the LEGO Crack House. I ask to tag along and hop in the car alongside Thomas Mueller, whom I bonded with while building the Yellow Castle wall on Friday night.

Less than five minutes later, we pull up to the back of a school building that looks much like the old middle school that houses the museum.

“Welcome to the LEGO Crack House,” Dan says with a spooky laugh, opening the door. Pallets are stacked haphazardly, boxes marked with “preschool” are lying around, and there are containers of Bionicle still shrink-wrapped in plastic. We go up to the second floor of the school, where the rooms are in various stages of organization. Pick A Brick boxes line the hallway. The “Chaos Room,” as Dan calls it, has plastic bags of bricks waiting to be parted out and sorted. There’s another room filled with just DUPLO bricks; and a third classroom shows signs of Dan’s previous life, with boxy computer monitors sitting ten deep.

The paint is cracked and peeling in places, but this building, like the museum, is a gold mine, with more than 2.3 million bricks stacked on tan metal shelves. I have never seen so much LEGO in one place. Dan surprises me with a gift.

“This is wild,” he says as he hands me a dark blue Bionicle set with blank white paper on the box where the product normally would be advertised. The lack of graphics is intriguing; it feels as if anything could be inside. When I turn it over, I can see through the unwrapped portion of the clamshell case that blue LEGO system bricks are bagged inside the book-size box. It’s a bizarre packaging mistake—LEGO bricks and Bionicle are separate licenses—one that likely never should have shipped from the packing plant in Tennessee. Yet it’s here in Bellaire, Ohio, and frankly, I’m not surprised.

14

Becoming a Brickmaster

This is a 13,824-piece mosaic of the Star Wars icon Yoda—forty-five by thirty inches of LEGO art by Brickworkz’s Brian Korte.

I return from my trip to Bellaire with a renewed sense of purpose as a builder. After being surrounded by intricate models for four days, I feel compelled to improve my skill set and try to learn to build like the master model builders. It’s a bit egotistical, but I want Dan Brown one day to covet something that I’ve built. However, I remind myself that Daniel LaRusso didn’t just show up at the All-Valley Karate Championships ready to rumble; there was a whole series of skills he needed to master.

I also have a more immediate goal. In the wake of failing to build a horse at Brick Show, I need to expand my repertoire of LEGO animal constructions beyond the camel. I grab a bucket of yellow parts and spill them onto the dining room table. The bricks form a loose shape, like tea leaves, and in them I see the beginnings of a project. A rudder piece from the Aqua Raiders set that I used in the Belville challenge approximates a whale’s tail, and a small pile of inverted 2 × 2 slopes could be the creature’s bottom jaw. A window becomes an oversize eye, and I use a SNOT (Studs Not On Top) technique to add fins at ninety-degree angles to the whale’s body. This is not a model built to scale, but it is instantly recognizable. I think that’s because I nailed something simple: the whale’s mouth. An inverted 2 × 3 slope rests below an inverted 2 × 2 slope, leaving a slight indent, which suggests the trademark half-smile that all cartoon whales seem to share.

I inform Kate that I am now a BrickMaster. She likes the whale, but she’s skeptical about the honorific until I show her the

BrickMaster

magazine and Bionicle set that have arrived in the mail.

LEGO Club

is the free product magazine that anyone can receive; but if you are willing to pay $39.99 a year, you will receive six

BrickMaster

magazines, six exclusive sets to build, and the right to be called a BrickMaster—“the ultimate LEGO fan.”

BrickMaster

magazine and Bionicle set that have arrived in the mail.

LEGO Club

is the free product magazine that anyone can receive; but if you are willing to pay $39.99 a year, you will receive six

BrickMaster

magazines, six exclusive sets to build, and the right to be called a BrickMaster—“the ultimate LEGO fan.”

“LEGO segments their customer base with different types of content,” wrote Joe Pulizzi in a June 2008 entry on his blog. “While

LEGO

magazine is great for many of their customers, a good portion of their customer base, which I would consider the ‘high-spenders,’ need more attention and have more advanced content needs. Thus,

BrickMaster

was born.”

LEGO

magazine is great for many of their customers, a good portion of their customer base, which I would consider the ‘high-spenders,’ need more attention and have more advanced content needs. Thus,

BrickMaster

was born.”

Joe is an adult fan. He also happens to be one of the Web’s leading thinkers on content marketing. The consultant started analyzing his attraction to LEGO once he started building again with his two adolescent boys. Joe remembers getting the original

Brick Kicks

magazine in the 1980s. Just like

BrickMaster,

it was a bimonthly publication that focused on LEGO builders talking about innovative models and wacky uses of LEGO. The Spring 1989 edition featured a profile of thirty-eight-year-old “Tricky Dick,” a tortoise in Britain that had a set of LEGO wheels attached to compensate for a right hind leg lost to a dog bite.

Brick Kicks

magazine in the 1980s. Just like

BrickMaster,

it was a bimonthly publication that focused on LEGO builders talking about innovative models and wacky uses of LEGO. The Spring 1989 edition featured a profile of thirty-eight-year-old “Tricky Dick,” a tortoise in Britain that had a set of LEGO wheels attached to compensate for a right hind leg lost to a dog bite.

“Getting kids and adults involved in being a LEGO fan is all about imagination. They give you the sets, of course, to start, but LEGO cultivates that through all of their contests. It’s about creating, thinking outside the instruction manual,” says Joe when I reach him by phone in his Cleveland office.

The spirit of creative competition celebrated in

Brick Kicks

is still on display at AFOL conventions, with builders pushing one another to find more imaginative uses for parts. White and translucent bricks look like smoke floating up from a chimney, gearshifts become bunny ears on a television, and radio dishes are patio umbrellas. The scale of creations at those conventions could be lifted directly from the pages of the magazines—models that seemingly were being built only by master builders in the 1980s.

Brick Kicks

is still on display at AFOL conventions, with builders pushing one another to find more imaginative uses for parts. White and translucent bricks look like smoke floating up from a chimney, gearshifts become bunny ears on a television, and radio dishes are patio umbrellas. The scale of creations at those conventions could be lifted directly from the pages of the magazines—models that seemingly were being built only by master builders in the 1980s.

“Anybody who likes LEGO wants to share their creation. You want to take pictures of it, put it online, get comments, and make friends,” says Joe.

With

BrickMaster,

LEGO appears to be developing the next wave of adult fans in the same manner as the generation that grew up reading

Brick Kicks.

Inside the magazine, kids are celebrated as builders with the “cool creations” section; but today the company is taking advantage of technology to connect fans with one another. MyLEGO Network is a social networking site that lets kids show one another their MOCs and play LEGO-themed video games. It stands to reason that kids with large LEGO collections are more likely to keep building through the Dark Ages and become adult fans.

BrickMaster,

LEGO appears to be developing the next wave of adult fans in the same manner as the generation that grew up reading

Brick Kicks.

Inside the magazine, kids are celebrated as builders with the “cool creations” section; but today the company is taking advantage of technology to connect fans with one another. MyLEGO Network is a social networking site that lets kids show one another their MOCs and play LEGO-themed video games. It stands to reason that kids with large LEGO collections are more likely to keep building through the Dark Ages and become adult fans.

Other books

Killing Red by Perez, Henry

314 by A.R. Wise

Hush Hush by Lippman, Laura

Forest Moon Rising by P. R. Frost

Guns to the Far East by V. A. Stuart

Social Blunders by Tim Sandlin

Every Woman for Herself by Trisha Ashley

Little Brother of War by Gary Robinson

Kindergarten Baby: A Novel by Cricket Rohman

Glass Heart by Amy Garvey