Lenin: A Revolutionary Life (27 page)

Lenin’s bombshell came in the form of a letter to the Central Committee and the Moscow and Petrograd Committees of the Party written, like the above, between 12 and 14 September (OS). The uncompromising first sentence said it all: ‘The Bolsheviks, having obtained a majority in the Soviets of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies of both capitals, can and

must

take state power into their own hands.’ [SW 2 362] This was the first of an ever-increasingly strident series of missives sent by Lenin to a variety of Party bodies but they all revolved around the message contained in that first sentence. No more pretence about peaceful development or power-sharing: the emergence of Bolshevik majorities in the soviets meant the time for decisive, unilateral, revolutionary action had come. The language Lenin uses in his series of letters and articles betrays a desperate sense of urgency. Power must be taken ‘at this very moment’ [SW 2 363]. ‘History will not forgive us if we do not assume power now.’ [SW 2 363] Opposition to the idea is ‘the most vicious and probably most widespread distortion of Marxism’ resorted to by opportunists. ‘Vacillations may

ruin

the cause.’ [CW 26 58] ‘The crucial point of the revolution in Russia has undoubtedly arrived.’ [SW 2 372] ‘To miss such a moment and to “wait” for the Congress of Soviets would be

utter idiocy

,or

sheer treachery

.’ [SW 2 378] ‘To refrain from taking power now … is

to doom the revolution to failure

.’ [SW 2 380] ‘Procrastination is becoming positively criminal.’ [SW 2 424] ‘Delay would be fatal.’ [SW 2 432 repeated SW 2 433] ‘Everything now hangs by a thread.’ [SW 2 449]

Apart from the obvious fact that, at the end of the day, it was successful, Lenin’s campaign has a number of interesting features. In the first place, Lenin’s mounting frenzy was occasioned by the fact that, amazingly, he was not being listened to. When the first letter arrived it was proposed that it should be burned as a dangerous piece of evidence that might endanger the whole party. Following further pressure he was so frustrated by 29 September (OS) that he offered to resign from the Central Committee, a possibility the Central Committee itself did not take seriously. Nor, however, were they prepared to give in to what they saw as a far-fetched demand of Lenin that power should be seized. His colleagues believed his isolation from Petrograd encouraged the breeding of what they saw as unrealistic demands, as fantasies.

Lenin, however, did not. He took the idea deadly seriously and resorted to further stratagems to get round their resistance. In writing, in the first place, to both Petrograd and Moscow he was partly fishing for support. Either would do. ‘By taking power in Moscow and Petrograd

at once

(it doesn’t matter which comes first, Moscow may possibly begin), we shall win

absolutely and unquestionably

.’ [SW 2 364] By 1 October (OS) he was also sending his crucial letter not only to the three committees but also to the Bolshevik members of the Petrograd and Moscow Soviets. Again he invited Moscow to begin if it thought it could. By 7 October (OS) in a letter to the Petrograd City Conference of the Bolshevik Party he was looking to the Baltic Fleet to perhaps kick off the revolution. The following day he wrote to the Bolshevik delegation to the Congress of Soviets of the Northern Region meeting in Helsinki urging that ‘the fleet, Kronstadt, Vyborg, and Revel [Tallin] can and must advance on Petrograd.’

5

[SW 2 433] By this time, having met only delay on the part of everyone else, Lenin took the ultimate step of returning to Petrograd, though, still as cautious as ever, he remained in hiding, staying in the apartment of a Party worker named Marguerita Vasilevna Fofanova. A meeting of the Central Committee was set up for 10 October (OS) in the apartment of the Menshevik-Internationalist

N.N. Sukhanov and his wife Galina Flakserman who was a Bolshevik. Despite talking all night and resolving to put armed uprising on the agenda, Lenin had still not got his way. At a further meeting called for 16 October (OS) his frustration was still patently obvious. According to the minutes he commented that ‘if all resolutions were defeated in this manner, one could not wish for anything better.’

6

Even worse was to come two days later when, in an open letter published in Gorky’s paper

Novaia zhizn’

, Kamenev and Zinoviev, the two leading figures in the Party after Lenin, made public their opposition to a Bolshevik seizure of power, thereby revealing what was, in any case, pretty much an open secret that the Bolsheviks were conspiring against the government. Lenin was merciless in his denunciation of them. They were strikebreakers, traitors and blacklegs. Terms such as ‘evasive’, ‘slanderous’ and ‘despicable’ peppered Lenin’s letter. At a meeting of 20 October (OS) the Central Committee took a less serious attitude to the article than Lenin, merely calling for the two to submit to Party discipline rather than, as Lenin wanted, expelling them from the Party.

Clearly, while Lenin was undoubtedly the dominant figure in the Party leadership, even he could not snap his fingers and get his way. It is also significant that, within days, despite the extreme invective, Lenin was working closely and harmoniously with Kamenev and Zinoviev. Once again, the political Lenin was in evidence. First he did not spare his close friend and fellow exile, Zinoviev, from coruscating criticism, like that which had rained down on the heads of Martov, Plekhanov, Bogdanov and many others in the past. But also, the moment passed once the political issue was resolved and they were prepared to return to the Bolshevik camp and accept Party discipline. Lenin dropped the invective as quickly as it had arisen. Like the much longer-lasting polemic against Trotsky, once it was over it was almost as though it had never happened. In interpreting Lenin’s more outspoken and extreme statements we must remember that Lenin’s political instinct worked in both directions to overrule personal feelings. He could sacrifice friendship in order to break a political relationship. He could also ignore former animosities to build a new alliance. In this light, one should take more seriously Lenin’s thoughts at various times about reuniting even with SRs and Mensheviks. If the political terms changed and came right, Lenin might well have been prepared in practice to ally with them as he claimed he would in his writings. However, the preliminary condition would have to be fulfilled. The politics would, indeed, have to be right!

The final aspect of Lenin’s campaign for an insurrection lies in the arguments he used to promote his policy. The urgency of his campaign was driven above all by the fact that the Bolsheviks had obtained majorities in the county’s two leading soviets. However, this did not mean that those soviets were controlled by the Bolsheviks or that the majority of members actually understood Bolshevik objectives. What it meant above all was that they were prepared to support a party which opposed the Provisional Government and stood firmly in favour of soviet power. That the Bolsheviks also proposed a magical incantation against the war – peace without annexations or reparations – also helped even though it was in practice undeliverable and had, lurking behind it,

Plate 1

The Ulyanov family in Simbirsk, 1879, Vladimin is bottom right © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

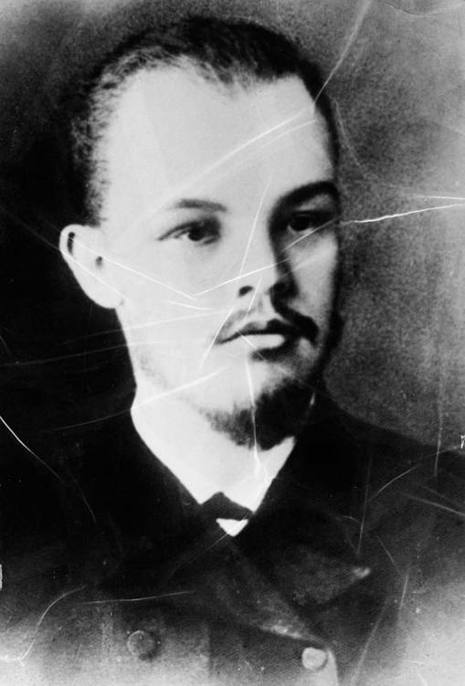

Plate 2

Lenin as a university student, 1891 © Bettmann/CORBIS

Plate 3

Lenin and the Petersburg League of Struggle, 1895. Lenin is in the centre seated behind the table. © Bettmann/CORBIS

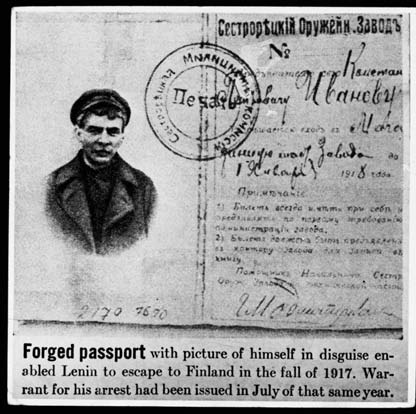

Plate 4

Forged passport, 1917 © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS

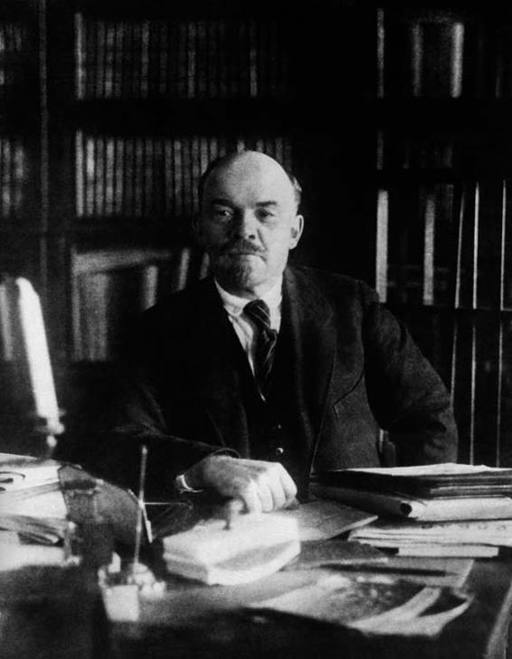

Plate 5

Lenin sitting at his desk, c. 1921 © Bettmann/CORBIS

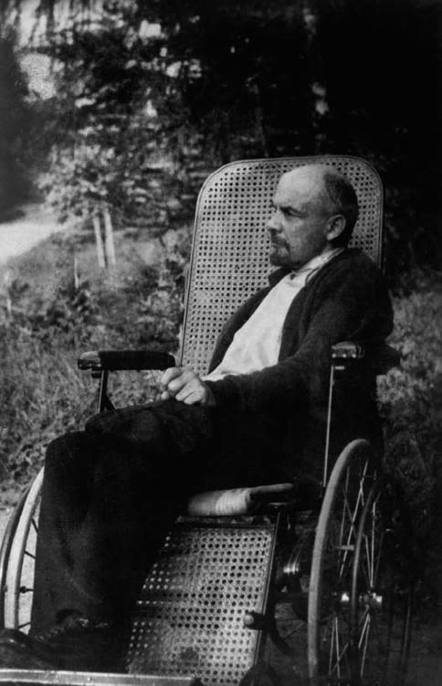

Plate 6

Lenin, Krupskaya and children on a bench, 1922 © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS