Leon Uris (32 page)

“You have no right to ask that.”

“You are begging for the life of one girl. I am begging for the lives of a quarter of a million people.”

She rose. “I had better get back to work. Ari, you knew why I wanted to come on board the

Exodus

. Why did you let me?”

He turned his back to her and looked from the window out to sea where the cruiser and destroyers stood watch. “Maybe I wanted to see you.”

Hunger Strike/ Hour

#85

General Sir Clarence Tevor-Browne paced up and down Sutherland’s office. The smoke from his cigar clouded the room. He stopped several times and looked out the window in the direction of Kyrenia.

Sutherland tapped out his pipe and studied the array of sandwiches on the tray on the coffee table. “Won’t you sit down, Sir Clarence, and have a bite to eat and a spot of tea?”

Tevor-Browne looked at his wrist watch and sighed. He seated himself and picked up a sandwich, stared at it, nibbled, then threw it down. “I feel guilty when I eat,” he said.

“This is a bad business to be in for a man with a conscience,” Sutherland said. “Two wars, eleven foreign posts, six decorations, and three orders. Now I’ve been stopped in my tracks by a band of unarmed children. A fine way to end thirty years of service, eh, Sir Clarence?”

Tevor-Browne lowered his eyes.

“Oh, I know you’ve been wanting to talk to me,” said Sutherland.

Tevor-Browne poured some tea and sighed, half embarrassed. “See here, Bruce. If it were up to me ...”

“Nonsense, Sir Clarence. Don’t feel badly. It is I who feel badly. I let you down.” Sutherland rose and his eyes brimmed. “I am tired. I am very tired.”

“We will arrange a full pension and have the retirement as quiet as possible. You can count on me,” Tevor-Browne said. “See here, Bruce. I stopped over in Paris on my way here and I had a long talk with Neddie. I told her about your predicament. Listen, old boy, with some encouragement from you, you two could get together again. Neddie wants you back and you’re going to need her.”

Sutherland shook his head. “Neddie and I have been through for years. All we ever had between us that was meaningful was the Army. That’s what held us together.”

“Any plans?”

“These months on Cyprus have done something to me, Sir Clarence, especially these past few weeks. You may not believe this, but I don’t feel that I’ve suffered a defeat. I feel that I may have won something very great. Something I lost a long time ago.”

“And what is that?”

“Truth. Do you remember when I took this post? You told me that the only kingdom that runs on right and wrong is the kingdom of heaven and the kingdoms of the earth run on oil.”

“I remember it well,” Tevor-Browne said.

“Yes,” Sutherland said, “I have thought so much about it since this

Exodus

affair. All my life I have known the truth and I have known right from wrong. Most of us do. To know the truth is one thing. To live it ... to create the kingdom of heaven on earth is another. How many times in a man’s life does he do things that are repulsive to his morality in order to exist? How I have admired those few men in this world who could stand up for their convictions in the face of shame, torture, and even death. What a wonderful feeling of inner peace they must have. Something that we ordinary mortals can never know. Gandhi is such a man.

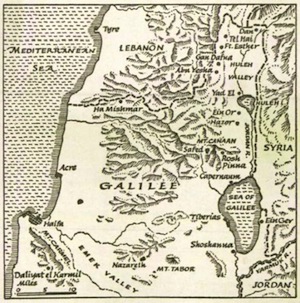

“I am going to that rotten sliver of land that these Jews call their kingdom of heaven on earth. I want to know it all ... Galilee, Jerusalem ... all of it.”

“I envy you, Bruce.”

“Perhaps I’ll settle down near Safed ... on Mount Canaan.”

Major Alistair entered the office. He was pale and his hand shook as he gave Tevor-Browne a note to read. Tevor-Browne read it and reread it and could not believe his eyes. “Great God, save us all,” he whispered. He passed the note to Bruce Sutherland.

URGENT

Ari Ben Canaan, spokesman for the Exodus, announced that beginning at noon tomorrow ten volunteers a day will commit suicide on the bridge of the ship in full view of the British garrison. This protest practice will continue until either the Exodus is permitted to sail for Palestine or everyone aboard is dead.

Bradshaw, with Humphrey Crawford and half a dozen aides, sped out of London to the quiet of a peaceful, isolated little house in the country. He had fourteen hours to act before the suicides on the

Exodus

began.

He had badly miscalculated the entire thing. First, the tenacity and determination of the children on the ship. Second, the powerful propaganda the incident created. Finally, he had not imagined that Ben Canaan would take the offensive and press the issue as he had. Bradshaw was a stubborn man but he knew when he was defeated, and he now turned his efforts to making a face-saving settlement.

Bradshaw had Crawford and his aides cable or phone a dozen of the top Jewish leaders in England, Palestine, and the United States to ask them to intervene. The Palestinians, in particular, might possibly dissuade Ben Canaan. At the very least they could stall the action long enough to enable Bradshaw to come up with some alternate plans. If he could get Ben Canaan to agree to negotiate then he could talk the

Exodus

to death. Within six hours, Bradshaw had his answers from the Jewish leaders. They answered uniformly: WE WILL NOT INTERCEDE.

Next Bradshaw contacted Tevor-Browne on Cyprus. He instructed the general to inform the

Exodus

that the British were working out a compromise and to delay the deadline for twenty-four hours.

Tevor-Browne carried out these instructions and relayed Ben Canaan’s answer back to England.

URGENT

Ben Canaan informed us there is nothing to discuss. He says either the Exodus sails or it doesn’t sail. He further states that complete amnesty to the Palestinians aboard is part of the conditions. Ben Canaan summarized: Let my people go.

Trevor-Browne

Cecil Bradshaw could not sleep. He paced back and forth, back and forth. It was just a little over six hours before the children on the

Exodus

would begin committing suicide. He had only three hours left in which to make a decision to hand to the Cabinet. No compromise could be reached.

Was he fighting a madman? Or was this Ari Ben Canaan a shrewd and heartless schemer who had deftly led him deeper and deeper into a trap?

LET MY PEOPLE GO

!

Bradshaw walked to his desk and flicked on the lamp.

URGENT

Ari Ben Canaan, spokesman for the

Exodus,

announced that beginning at noon tomorrow ten volunteers a day will commit suicide ...

Suicide ... suicide ... suicide ...

Bradshaw’s hand shook so violently he dropped the paper.

Also on his desk were a dozen communiqués from various European and American governments. In that polite language that diplomats use they all expressed concern over the

Exodus

impasse. He also had notes from each of the Arab governments expressing the view that if the

Exodus

were permitted to sail for Palestine it would be considered an affront to every Arab.

Cecil Bradshaw was confused now. The past few days had been a living hell. How had it all begun? Thirty years of formulating Middle Eastern policy and now he was in his worst trouble over an unarmed salvage tug.

What queer trick of fate had given him the mantle of an oppressor? Nobody could possibly accuse him of being anti-Jewish. Secretly Bradshaw admired the Jews in Palestine and understood the meaning of their return. He enjoyed the hours he had spent arguing with Zionists around conference tables, bucking their brilliant debaters. Cecil Bradshaw believed from the bottom of his heart that England’s interest lay with the Arabs. Yet the Mandate had grown to over half a million Jews. And the Arabs were adamant that the British were fostering a Jewish nation in their midst.

During all the years of work he had been realistic with himself. What was happening? He could see his own grandchildren lying on the deck of the

Exodus.

Bradshaw knew his Bible as well as any well brought-up Englishman and like most Englishmen had a tremendous sense of honor although he was not deeply religious. Could it be that the

Exodus

was driven by mystic forces? No, he was a practical diplomat and he did not believe in the supernatural.

Yet—he had an army and a navy and the power to squash the

Exodus

and all the other illegal runners—but he could not bring himself to do it.

The Pharaoh of Egypt had had might on his side too! Sweat ran down Bradshaw’s face. It was all nonsense! He was tired and the pressure had been too great. What foolishness!

LET MY PEOPLE GO

!

Bradshaw walked to the library and found a Bible and in near panic began to read through the pages of Exodus and about the Ten Plagues that God sent down on the land of Egypt.

Was he Pharaoh? Would a curse rain down on Britain? He went back to his room and tried to rest, but a staccato rhythm kept running through his tired brain ... let my people go ... let my people go ...

“Crawford!” he yelled. “Crawford!”

Crawford ran in, tying his robe. “You called?”

“Crawford. Get through to Tevor-Browne on Cyprus at once. Tell him ... tell him to let the

Exodus

sail for Palestine.”

The Land is Mine

... for the land is mine: for ye are strangers and sojourners with me. And in all the land of your possession ye shall grant a redemption for the land.

The word of God as given to

Moses in Leviticus

T

HE BATTLE OF THE

E

XODUS

was over!

Within seconds, the words “

Exodus

to sail” were on the wires. Within minutes they blazed in headlines around the world.

On Cyprus the joy of the people was boundless and around the world there was one long sigh of relief.

On the

Exodus

the children were too exhausted to celebrate.

The British urged Ari Ben Canaan to bring the salvage tug to dockside so that the children could be given medical care and the ship restocked and inspected. Ben Canaan agreed, and as the

Exodus

pulled in, Kyrenia turned into a mad scramble of activity. A score of British army doctors swarmed onto the ship and quickly removed the more severe cases. A hastily improvised hospital was established at the Dome Hotel. Rations and clothing and supplies poured onto the dock. In addition, hundreds of gifts from the people of Cyprus deluged the ship. Royal engineers combed the ancient tug from stem to stern to patch leaks, overhaul the motor, and refit her. Sanitation teams made her spotless.

After an initial survey Ari was advised it would take several days to get the children strong enough and the ship fit enough to make the day and a half run to Palestine. The small Jewish community on Cyprus sent a delegation to Ari to appeal to him to allow the children to celebrate the first night of Chanukah, the Festival of Lights, on Cyprus before sailing; the holiday was to begin in a few days. Ari agreed.

Only after Kitty had been assured and reassured that Karen’s condition was not serious did she allow herself the luxury of a steaming hot tub, a thick steak, a half pint of Scotch, and a magnificent, deep, seventeen-hour sleep.

Kitty awoke to a problem she could no longer avoid. She had to decide either to end the episode with Karen forever or to follow the girl to Palestine.

Late in the evening when Mark came into her room for tea she appeared none the worse for her ordeal. In fact, the long sleep had made her look quite attractive.

“Newsroom still hectic?”

“Matter of fact, no,” Mark answered. “The captains and the kings are departing. The

Exodus

is day-old news now ... the kind they wrap fish in. Oh, I suppose we can drum up a final page-one picture when the boat lands in Haifa.”

“People are fickle.”

“No, not really, Kitty. The world just has a habit of moving on.”

She sipped her tea and sank into silence. Mark lit a cigarette and propped his feet on the window sill. He pretended his fingers were a pistol and pointed over his shoe tops out at the pier.

“What about you, Mark?”

“Me? Old Mark Parker has worn out his welcome in the king’s domains. I’m going Stateside and then maybe take a crack at the Asian beat. I’ve had an itch to go there anyhow ... I hear it runs crosswise.”

“The British won’t let you into Palestine?”

“Not a chance. I am held in very low esteem. In fact if they weren’t proper Englishmen I’d say they hate my guts. Frankly, I don’t blame them.”

“Give me a cigarette.”

Mark lit one and handed it to her. He bided his time, continuing to take target practice with his imaginary pistol.

“Damn you, Mark! I hate that smug way you have of reading my mind.”

“You’ve been a busy little girl. You went to the British authorities to ask permission to enter Palestine. Being the gentlemen they are, they opened the door for you and bowed. You were just a clean-cut American girl doing her duty. Of course, CID doesn’t know about your little rumrunning act for Aliyah Bet. Well ... are you going or not?”