Let's Ride (8 page)

Authors: Sonny Barger

The different needs of American riders and European riders go back so far that you can see them reflected in the types of saddles used on horses. American-style saddles put the rider in a roomy, stretched-out, upright position; European-style saddles had the rider leaning forward in a racer-type crouch, his or her legs tucked up behind.

When the Europeans, particularly the Brits, started modifying their motorcycles, instead of building long, low, stretched-out choppers, they copied European horse riding: low-mounted handlebars, footpegs set high and back, and cut-down saddles. This put the rider into a forward-leaning racer-type riding position. The Brits called this kind of custom a “café racer,” because their riders often raced from one café to another.

This style of motorcycle was slow to catch on in the United States. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s most European and Japanese manufacturers equipped bikes sold in Europe with low handlebars and rearset footpegs, whereas bikes shipped to the U.S. market featured lower, forward-mounted footpegs and higher handlebars, which were often called “western-style” bars, because they had a sort of cowboylike look to them.

BMW brought the R90S, a café racer with a small fairing—more of a headlight shroud, since it didn’t do much to protect the rider from the elements—to the U.S. market in 1973. Harley followed suit with the XLCR Sportster (“XL” is Harley’s designation for the Sportster engine, and “CR” stood for “café racer”) in 1977, but its model wasn’t very successful and was the last sport-type motorcycle to wear the Harley brand until the recently introduced XR1200. Other than an oddball European bike imported into the country in extremely small quantities, café racers were thinly represented in the United States in the 1970s.

That was about to change, thanks in large part to the development of superbike racing. By the mid-1970s road-racing motorcycles had become so specialized that they literally no longer shared a single part with their road-going counterparts. At that time most road bikes were powered by large-displacement four-stroke engines while road-racing bikes were powered almost exclusively by purpose-built two-stroke mid-displacement engines.

Historically motorcycle racing had been something that an average motorcyclist could do. Back in the early days most clubs formed around racing; early clubs like the Boozefighters focused as much on racing as they did on raising hell. Remember, this was a time when you’d ride one motorcycle to work every day, then race that same bike on the weekend. But by the 1970s a person who wanted to race competitively had to buy a purpose-built race bike that cost half a year’s salary, if you had a good job. Racing had changed from something that anyone with a motorcycle could do into an elite activity.

At just about the time that two strokes completely took over the top levels of racing, an alternative form of racing based on production bikes started to gain popularity. This happened when the Japanese introduced their big, powerful four-cylinder machines. Magazines called these “superbikes,” so the production class in which these motorcycles raced became known as the “superbike” class.

Production-based classes reinvigorated the sport of motorcycle racing at a grassroots level. In the early days of superbike racing, anyone with $2,500 could walk into one of the thousands of Kawasaki or Suzuki shops that could be found in any small town and buy a production bike capable of being built into a competitive racer. Within a few years thousands of people were competing in club races all across the United States. Due to the popularity of this type of racing, manufacturers began offering sportier and sportier motorcycles. Racers liked these bikes because it was less work (and less expense) to convert them into race bikes, but a lot of nonracers bought them, too, just because they liked the style of the bikes.

At first these bikes differed little from the standard bikes of the day. They had lower handlebars, maybe a small café-racer fairing, or at least a set of footpegs moved back a few inches from the standard position. But as superbike racing grew in popularity, the manufacturers got into the sport with factory-supported teams, which meant they started making production bikes with specifications that approached those of full-on race bikes. This is how we got the first factory crotch rockets, the Honda Interceptors, Kawasaki Ninjas, Yamaha FZRs, and Suzuki GSX-Rs.

These bikes became more and more capable, until they reached a point where it was virtually impossible (and completely insane) for riders to come anywhere near reaching their limits on public roads. Today’s crotch rockets are more potent than the pure racing bikes of a generation ago.

High-performance sport bikes are poor choices for beginners. Any of the 600-cc class sport bikes qualifies as one of the highest-performance machines you can buy of any type; probably only Formula 1 race cars generate more power per cubic inch than the engines in 600-cc sport bikes. But as mentioned in the last chapter, sport bikes don’t generate much torque. Because of this they are difficult for a newer rider to ride smoothly in traffic.

In fact, I don’t recommend anyone use modern sport bikes for daily transportation on public roads. I dislike telling people what they should and shouldn’t ride, and if you want to ride a crotch rocket, you have the freedom to do so—sport bikes are popular and a lot of people use them for everyday transportation without any problems. But that said, I believe this type of motorcycle is best left to the racetrack. It’s great fun to get out on a track and put your knees down on the pavement in high-speed corners, but out on the street that type of riding will just get you killed, and probably sooner rather than later. And when you’re riding on this type of bike, you’ll be tempted to ride it like you stole it every time you throw your leg over the saddle.

Even if you have the self-restraint needed to keep from exploring your motorcycle’s limits on public roads, sport bikes are excruciatingly uncomfortable to ride. The racer crouch is ideal when you’re on a track, throwing yourself from side to side, putting your knee down in the corners, and accelerating hard in the straights, but for the rest of the time, riding laid out over the gas tank puts a lot of strain on your body.

Sport bikes are especially bad in stop-and-go traffic, where you have to crane your neck back so far to see what’s going on around you that your head is likely to stick in that position. Unless you’re extremely young (and I mean young, like so young your fontanel has barely hardened over), if you put serious miles on a sport bike, you’d better keep a chiropractor on your payroll.

Standards

In 1980 most of the motorcycles you could buy were still basic do-it-all type machines, much like the BSA Gold Star had been thirty years earlier. Most companies built a basic type of motorcycle and only modified it slightly for different uses. To make a cruiser, a company would take its basic bike, add a pull-back handlebar and a stepped saddle (the magazines called them “buckhorn” bars and “king-queen” saddles back then), and give it a coat of black paint. The same bike might get a square headlight and a square plastic rear fender cover, maybe a fork brace or an oil cooler, and that would be sold as the sport-bike version.

The only companies making touring bikes at that time were Harley-Davidson and BMW. The Japanese manufacturers began to offer touring and racing accessories, but these amounted to tinkering around at the margins; the basic motorcycle underneath remained more or less the same. But everything changed during the 1980s. Cruisers evolved into carbon copies of Harley-Davidson motorcycles, complete with V-twin engines; touring bikes sprouted barn-door-sized fairing and enough luggage capacity to carry the entire belongings of a small third-world village; and sport bikes developed full racing fairings, complete with uncomfortable racer positions. At the beginning of the decade you could count the number of bikes made with any sort of fairing on one hand; by the end of the decade the only bikes that didn’t have plastic fairings were the Harley-style cruisers.

As the 1990s rolled around, it seemed like no one was building an ordinary, all-around motorcycle anymore. The manufacturers noticed this and introduced what the motorcycle press called a “new” type of motorcycle: the standard. In reality, this was just the rebirth of the regular old all-around motorcycle. Like “sport-tourer,” “standard” is a bit of a garbage category. The only thing that most standards have in common is the lack of a fairing and luggage. Standards range from tiny beginner bikes like the Suzuki TU250 to BMW’s wild K1300R, which is a type of standard often called a “street fighter” (street fighters are standards in that they have no bodywork but have the guts of high-performance sport bikes).

Though some of the high-performance street fighters might be a handful for newer riders to control, generally speaking, standards make good choices for first bikes. They tend to have comfortable riding positions and tractable engines, and like most cruisers, they don’t have expensive bodywork to break when you inevitably drop your bike.

W

HAT

Y

OU

S

HOULD

K

NOW

- Don’t worry about what everyone else thinks; pick the bike you like.

- Custom choppers and antique bikes might look cool, but they aren’t practical to use as transportation.

- The less bodywork you have on a bike, the less it costs if you tip over, which is an important consideration for newer riders.

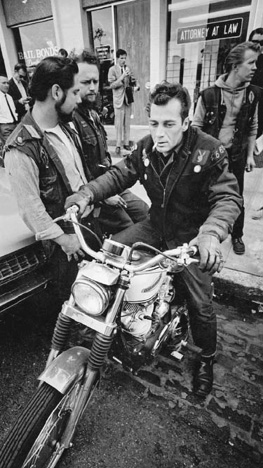

© by Gene Anthony

Y

ou may think the next logical step would be to buy a bike. After all, how can you learn to ride if you don’t have a bike? For most of the time I’ve been riding, the answer was that you couldn’t learn to ride unless you had a bike, but over the past twenty or so years that’s changed, thanks to the Motorcycle Safety Foundation. Originally formed in 1973, the MSF started out as a trade organization that promoted motorcycle manufacturers as much as it furthered safety. In some ways it still is that; its current sponsors are BMW, Ducati, Harley-Davidson, Honda, Kawasaki, KTM, Piaggio/Vespa, Suzuki, Triumph, Victory, and Yamaha, and ultimately the MSF serves those companies.

But early on the major bike companies figured out that one of the best ways the MSF could serve them was by helping to keep as many of their customers alive as possible. You’d be hard-pressed to find an organization that has done more to promote motorcycle safety than the MSF, not just in the past thirty-some years since it was founded, but ever. Back in the early years of the MSF, motorcycle fatalities were on the rise, and they had been for the previous decade. In 1980 motorcycle-related fatalities in the United States peaked at 5,144 deaths. That same year the MSF sponsored the first International Motorcycle Safety Conference. This marked the beginning of serious research into the causes of motorcycle-related deaths. The following year the government published

Motorcycle Accident Cause Factors and Identification of Countermeasures,

which is usually referred to as the “Hurt Report,” in honor of its primary author Harry Hurt.

Among its findings, the Hurt Report noted that 92 percent of riders involved in accidents lacked any formal motorcycle training; they were either self-taught, or they’d learned from family and friends. Apparently the riders’ friends had passed on their own bad habits, because the report noted: “Motorcycle riders in these accidents showed significant collision avoidance problems. Most riders would overbrake and skid their rear wheel, and underbrake the front wheel, greatly reducing collision avoidance deceleration. The ability to countersteer and swerve was essentially absent.”

Clearly someone needed to develop a formal motorcycle training course, but there was no obvious organization to handle that job. You might think the government would step in, but it seems that motorcycle riders are a low priority for most elected officials. The Hurt Report did nothing to light a fire under the government’s collective ass to start developing and funding rider training programs.

Thankfully, the MSF stepped up and did what all levels of government were unable to do: develop a rider training program. The MSF’s RiderCourse made its debut in California in 1987. Within a few years it had spread across the country. Not only do all states offer MSF RiderCourses, but the majority of them use some form of the RiderCourse curriculum in their licensing tests. Many states allow completion of the course itself to fulfill the riding skills portion of the licensing exam—complete the RiderCourse, get your motorcycle endorsement.

One of the best aspects of the RiderCourse is that in most states the program provides the motorcycles you’ll use to complete the course (and often earn your motorcycle license). That means that you can learn to ride without even buying a bike, which is why I put this chapter on learning to ride before the chapter on buying a motorcycle. Many of the programs that offer the courses even provide protective gear, which will save you hundreds or even thousands of dollars. Taking a RiderCourse is the best way to find out if you even like riding a motorcycle before you spend a small fortune buying a bike and all the associated gear.

I’m going to provide you with the basics of motorcycle riding in the following pages, but first I’m going to give you the single most important piece of advice in this entire book—

complete

the

MSF

RiderCourse.

And if you’re already an experienced motorcyclist who hasn’t taken the basic RiderCourse, take one of the advanced training courses. If you’re self-taught, or if you learned to ride from a friend or family member, chances are you’ve developed some bad habits over the years. Riding is an extremely high-risk activity and even if those bad habits haven’t caused you problems so far, sooner or later your luck will run out. It’s best to rely on luck as little as possible; one of the best ways to do that is to get formal training. It’s the most important thing you can do to avoid getting maimed or killed. I advise you to use what I write here to help familiarize yourself with the operation of a motorcycle to help you pass the MSF RiderCourse.

THE SIX BASIC CONTROLS

O

PERATING A MOTORCYCLE IS

a complex activity. You’ll need to use both of your hands and both of your feet to operate the controls, and you’ll often be using all of them at the same time. Remember, you’ll also need to use your feet to hold yourself up when the bike is stopped. Believe it or not, I’ve seen people forget this and fall over at a stop.

You’ll have to master six basic controls to ride most motorcycles. For the first twenty or so years I rode motorcycles, manufacturers used different layouts for these main controls. I only rode Harleys, but even though all the bikes I rode were built by the same manufacturer, the location of the brakes, shifters, and clutches varied from model to model and from year to year. Having to relearn the controls each time you bought a new bike annoyed the hell out of us, and it could even be dangerous at times, but for the 1975 model year the U.S. government passed a law standardizing the location of many of those controls. Since the U.S. motorcycle market was the most important one for most manufacturers, virtually all of them adopted the layout specified by U.S. law.

The main controls on a motorcycle are as follows:

- Throttle:

On a motorcycle the throttle is a twist grip that controls your speed, located on the right end of the handlebar. - Front brake lever:

This is a lever that controls the front brake, mounted on the right side of the handlebar, in front of the throttle. - Rear brake lever:

This is a lever that operates the rear brake, located near the right footpeg. - Clutch lever:

This is a lever that operates the clutch, located on the left side of the handlebar, in front of the left handgrip. - Shift lever:

This is a lever that shifts gears in the transmission, located near the left footpeg. - Handlebar:

Anyone who’s ridden a bicycle knows what this is.

SECONDARY CONTROLS

I

N ADDITION TO THESE

six primary controls, you’ll have to operate a variety of secondary controls when you’re riding on public roads. The locations of these aren’t as standardized as are the locations for the primary controls, but the vast majority of motorcycle manufacturers use the same basic layout. Secondary controls include the following:

- Ignition switch.

This can be found in all sorts of odd places, from up by the instruments, to the top of the tank, to below the seat. This operates much like the switch in a car, except that it doesn’t actually start the bike, as it does in most cars. For that you’ll need to use . . . - The electric start button.

This button, which engages the electric starting motor, is usually found on the right handgrip. - The choke or enrichment circuit.

This is a lever, usually on the left handgrip, that engages a choke on carbureted bikes or an enrichment or fast-idle circuit on fuel-injected bikes. Up until just a few years ago all bikes had these, but as motorcycle fuel-injection technology advances, more and more bikes skip this control. - Engine kill switch.

This is an emergency shut-off switch for the engine. I rarely if ever find the need to use this. - Turn signals.

Like cars, all modern street bikes have turn signals. The location and method of operation used for these varies a bit among some manufacturers—particularly Harley-Davidson and BMW—but on most bikes the control consists of a switch on the left handgrip that you push left to engage the left turn signal, push right to engage the right turn signal, and push straight in to turn off the signals. Unlike all modern cars, many bikes don’t have self-canceling turn signals, so you’ll need to remember to shut these off or you’ll be riding down the road with your signal flashing. In addition to being embarrassing, this can be dangerous. - Horn.

This is a button located on one of the handgrips—usually the left—that activates your motorcycle’s horn. Many people are afraid to use their horns because they think it’s rude, but it’s not nearly as rude as getting mangled by a car. If other drivers don’t see you, don’t worry about being rude; use your horn to let them know you’re there. It could save your life. - Headlight dimmer switch.

This works the same as the dimmer switch in your car. I don’t use this much because I always leave my headlight on high beam during the day, when I do most of my riding. - Speedometer.

This indicates your speed, just as it does in your car. Unlike cars, which usually feature analog speedometers, a lot of motorcycles use digital speedometers. - Tachometer.

This indicates your engine rpm, again just as it does in your car. Because almost all motorcycles use manual transmissions, these are much more useful on motorcycles than they are in cars, which mostly use automatic transmissions.

PRERIDE INSPECTION

M

OTORCYCLES HAVE COME A

long way since I started riding, but they still require more care and maintenance than cars. Even if a motorcycle was as reliable as a car, you’d still want to be extra diligent about making sure everything was in working order because the consequences of a system failing are much more extreme on a bike.

The MSF Experienced RiderCourse, which I have taken, teaches the following preride inspection technique, called “T-CLOCK”:

- T: Tires and wheels

- C: Controls

- L: Lights and electrics

- O: Oil and fluids

- C: Chassis and chain

- K: Kickstand

I’ll be honest; I check these items fairly regularly, but I don’t check each one every time I ride. Some items I do check, if not daily, almost every day. If I rode a bike with a chain, I’d check that every day, but I don’t: my bike uses a belt, which requires very little maintenance. I also check my tires and wheels every time I ride. I look them over to make certain they’re not damaged or low on air. I’ll visually inspect them to make sure they haven’t picked up any nails or glass, but I only check the air pressure once every two or three days unless I suspect one of them might have a leak.

Similarly I don’t check my oil level every day, at least on my Vision, which doesn’t burn a lot of oil. If I’m riding a Harley that I know burns some oil, I’ll check it often, sometimes more than once a day if I put on a lot of miles.

I’ll check my lights fairly regularly to make certain they’re working, especially my taillight and brake light, which I can’t see while I’m riding. The consequences of a malfunctioning taillight or brake light may be getting rear-ended by a car, and as you might imagine, that falls under the category of “really bad.” It seems like every car driver who has hit a motorcycle has said “I didn’t see the motorcycle.” Most of the time the real story is that the driver wasn’t paying attention, but in my opinion, if your taillight or brake light isn’t working, you’re as much at fault as the driver who just hit you.

I’m always paying attention to how my controls are working, but I can’t say I check these things every time I ride. Controls and cables on modern bikes are far more reliable than they were back when the MSF devised the T-CLOCK method. I do check for loose bolts in the chassis every now and then, but that was a bigger issue when I rode Harley-Davidson motorcycles, which vibrate much more than my Victory does. If you ride a Harley, you’ll probably want to check the bolts and nuts on a daily basis.

CHECKING TIRES

T

HE ONE THING

I do consider critical to check frequently is the air pressure in my tires. I’ve had tires go flat while I was flying down the road. I don’t want it to happen again if there’s anything I can do to help it. Besides, a motorcycle handles best when the tires are inflated to the proper pressure. Riding with the proper air pressure in your tires also ensures that your tires will last longer. This can save you a lot of money over time.

You’ll need to consult your owner’s manual to find out the proper pressure for your tires. On the sidewall of your tire you’ll find text saying something like: “Maximum Air Pressure 43 PSI.” That means that 43 pounds is the maximum air pressure your tire can safely handle, but that doesn’t mean that your bike was designed to operate with tires pumped up to 43 PSI. More likely your bike was designed to run in the 34–38 PSI range, and inflating your tires beyond that point will adversely affect handling and also cause your tires to wear out faster.

I always keep a tire pressure gauge in my motorcycle tool kit. I’ve found that it’s difficult to get a gauge on the valve stems on some motorcycles with a lot of luggage and bodywork. The area in which you will be working can be tight, and a long gauge can be difficult to seat properly on the valve stem. I carry a small round gauge with a dial instead of a long one with a stick that pokes out to indicate the air pressure; I find the smaller gauge is easier to maneuver around the tire and wheel.

When you check the air pressure, you should take a few seconds to make sure all the axle bolts and pinch bolts on the fork and shocks are tight. I once was riding with a buddy when the bolts securing the clamps that held his front axle in place came loose. His front wheel fell off and his bike went end over end in the ditch. Amazingly, he seemed all right after the incident, and so we continued on our way to the rally we were attending. But to this day he remembers nothing of that weekend.