Letters From Prison (33 page)

Read Letters From Prison Online

Authors: Marquis de Sade

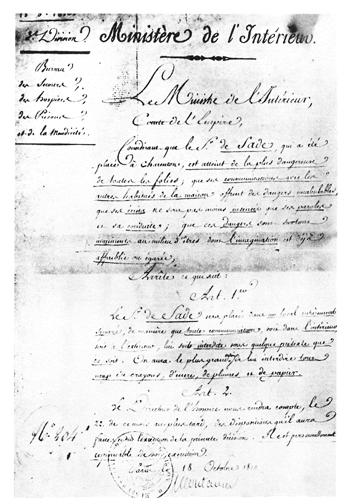

above and facing page:

The original of a letter from Sade to his wife dated June 25, 1780, in which he responds to a letter from her in which she dangles before him all the things he will do “when I get out.” The only problem, Sade notes, is that she fails to mention just when that magic date might be. Sade expresses his fear that when that day finally does come he may be “shipped off to some distant place” in exile, for he has an obsessive fear of ships and sailing.

See letter 28, p. 157.

COLLECTION RICHARD SEAVER

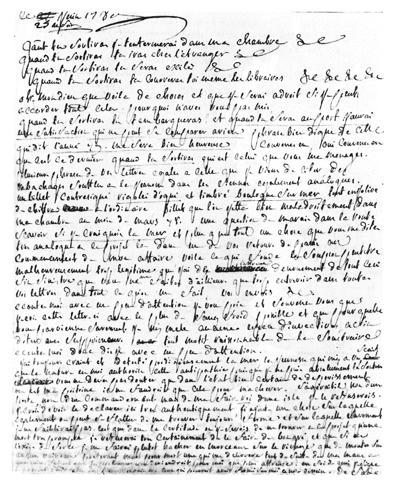

ABOVE AND FACING PAGE:

The original of a letter dated October 11, 1782, from Madame de Sade to Mlle de Rousset, who was back at La Coste trying to keep the long-neglected chateau from falling into a state of complete disrepair The letter begins: “Since there is some hanky-panky going on relative to the [marquis’ s] study, about which I am quite convinced because of another matter altogether, which is no concern of yours, it is imperative we find another place, and inform me what it is, where we can store the most important things. I have therefore written to Gaufridy, instructing him to put all my letters in a locked drawer, without showing them to anyone.” One can only guess what information, or indiscretion, those letters might have contained.

COLLECTION RICHARD SEAVER

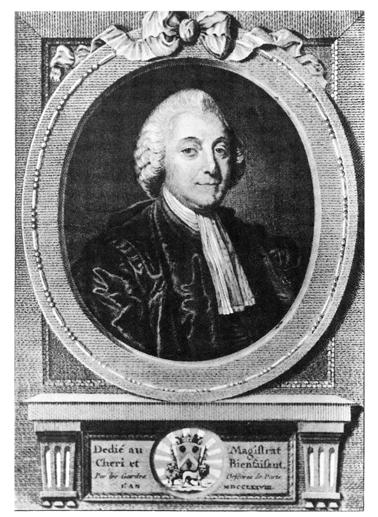

Jean-Charles Pierre Le Noir, lieutenant-general of the French police, held Sade’s fate in his hands. He succeeded Antoine de Sartine, a much harsher official whom Sade despised and writes about in several letters in the most scathing terms.

REPRINTED FROM PAUL GINI STY, LA MARQUISE DE SADE (PARIS: BIBLIOTHéQUE CHARPENTIER, 1901

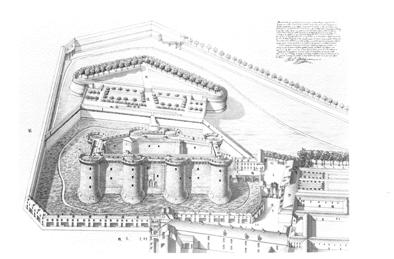

A bird’s-eye view of the Bastille. Note the extensive gardens where guards and family could walk. Prisoners’ walks were confined to the narrow space within the high prison walls.

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY DRAWING BY PALLOY, COLLECTION RICHARD SEAVER

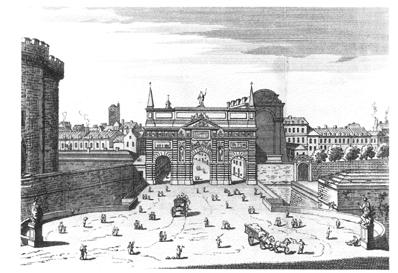

The Porte de Saint-Antoine, hard by the Bastille towers. On July 2, 1789, using a makeshift megaphone, Sade shouted from the window of his prison cell to the inhabitants and passersby below that the prisoners were being massacred and that the people should come and save them.

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGRAVING, COLLECTION RICHARD SEAVER

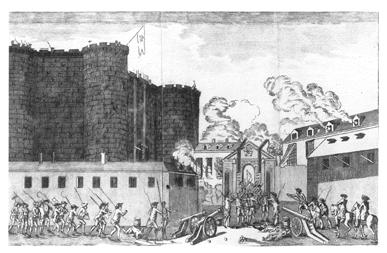

Twelve days after Sade’s rebellious act, the Bastille was stormed, and Warden de Launay and several of his aides were brutally murdered by the rampaging mob. By then, however, Sade had been removed to the insane asylum at Charenton.

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGRAVING BY DUPIN, COLLECTION RICHARD SEAVER

The Charenton Asylum. Sade was lodged on the second floor of the right wing of the hospital. Following his hasty removal from the Bastille just after midnight on July 3, 1789, Sade remained incarcerated in Charenton until April 2, 1790, which was Good Friday—a day, noted Sade, he intended to celebrate for the rest of his life.

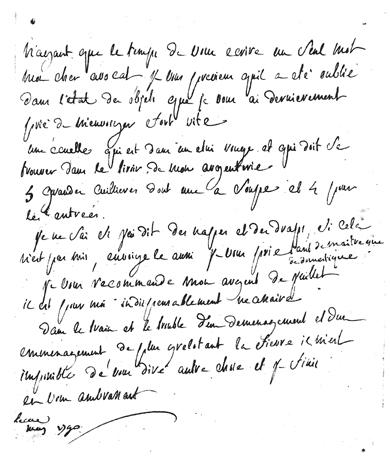

A letter from Sade to his longtime Provençal lawyer, Gaspard Gaufridy, written shortly after his release from Charenton. Dated only “May 1790,” it probably falls between letters 108 and 109 of the present volume. Sade, setting up his new household in Paris, is asking Gaufridy to go to La Coste and send him posthaste some silverware, sheets, and napkins, as well as, needed even more urgently, money. He also notes that he is ill, “shaking with fever.”

COLLECTION RICHARD SEAVER

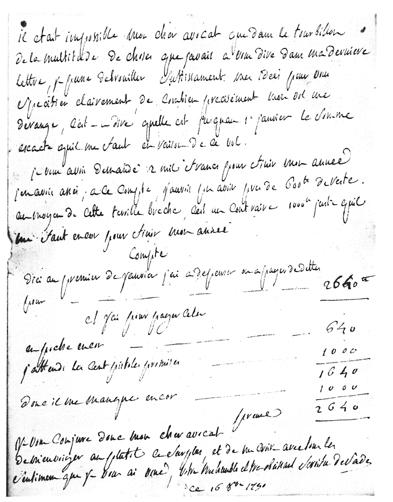

Another pleading missive to Gaufridy, dated three months later, August 16, 1790, detailing the exact sum he will need between then and January to clear his debts and survive. Noting precisely what he expects to receive, he still finds himself “a thousand francs short.”

COLLECTION RICHARD SEAVER