Liesl & Po (3 page)

Authors: Lauren Oliver

The truth was this: Will was lonely. During the day he studied with the alchemist, who was seventy-four years old and smelled like sour milk. At night he carried out the alchemist’s errands in the darkest, loneliest, most barren corners of the city. Before discovering the girl in the window, he had sometimes gone whole weeks without seeing a single living person besides the alchemist and the strange, bent, crooked, desperate people who wheeled and dealed with him in the middle of the night. Before her, he was used to moving in darkness and silence so thick it felt like a cloak, suffocating him.

The nights were cold, and damp. He could never get the chill out of his bones, no matter how long he sat by the fire when he returned to the alchemist’s house.

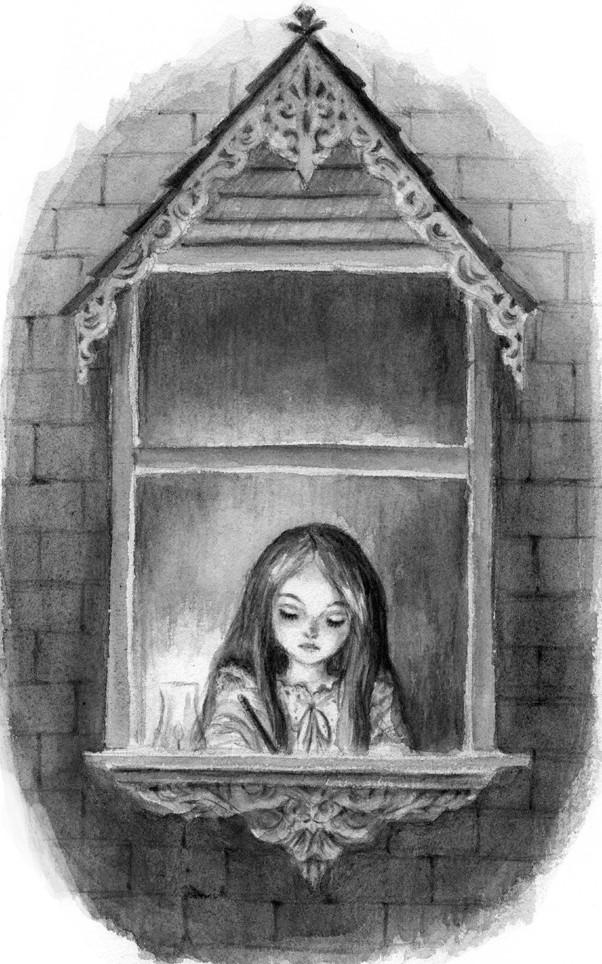

And then one night he had turned the corner of Highland Avenue and seen, at the very top of an enormous white house, all decorated with balconies and curlicues and designs that looked like frosting on a cake, a single warm light burning in a single tiny window like a single candle, and a girl’s face in it, and the face and the light had warmed him right to the very core. Since then he had seen her every night.

But for the past three nights the window had been dark.

Will shifted the box from his left arm to his right. He had been standing on the sidewalk a long time, and the box had grown heavy. He did not know what to do. That was the problem. Above all he feared that something bad had happened to the girl, and he felt—strangely, since he had never met her or spoken a word to her in his life—that he would not forgive himself if that were the case.

He stared at the stone porch and the double doors that loomed behind the iron gate at 31 Highland Avenue. He thought about going through the gate and up the stairs and knocking with that heavy iron knocker.

“Hello,” he would say. “I’m wondering about the girl in the attic.”

Useless

, the alchemist would say.

“Hello,” he would say. “During my nightly walks I could not help but notice the girl who lives upstairs. Pretty, with a heart-shaped face. I haven’t seen her in several days and just wanted to see if everything is okay? You can tell her Will was asking for her.”

Pathetic

, the alchemist would say.

Worse than useless. As ridiculous and deluded as a frog trying to turn into a flower petal. . . .

Just as the alchemist’s remembered lecture was gaining steam in Will’s overtired and indecisive mind, the miraculous happened.

The attic light went on, and against its small, soft glow Liesl’s head suddenly appeared. As always, her face was tilted downward, as though she was working on something, and for a moment Will had fantasies (as he always did) that she was writing him a letter.

Dear Will

, it would say.

Thank you for standing outside my window every night. Even though we’ve never spoken, I can’t tell you how useful you have been to me. . . .

And even though Will knew that this was absurd because (1) the girl in the window didn’t know his name, and (2) she almost certainly couldn’t see him standing in the pitch-black from a well-lit window, just seeing the girl and imagining the letter made him incredibly, immensely happy—so happy he didn’t have a word for it, so happy it didn’t feel like other kinds of happiness he knew, like getting to eat a meal when he was hungry, or (occasionally) sleep when he was very tired. It didn’t even feel like watching the clouds or running as fast as he could when no one was looking. This feeling was even lighter than that, and also more satisfying somehow.

Standing on the dark street corner with the black, quiet night squeezing him like a fist from all sides, Will suddenly remembered something he had not thought of in a very long time. He remembered walking home from school to the orphanage, before he had been adopted by the alchemist, and seeing Kevin Donnell turn left in front of him and pass through a pretty painted gate.

It was snowing, and late, and already getting dark, and as Will had passed by Kevin Donnell’s house, he had seen a door flung open. He had seen light and warmth and the big, comforting silhouette of a woman inside of it. He had smelled meat and soap and heard a soft trilling voice saying,

Come inside, you must be freezing. . . .

And the pain had been so sharp and deep inside of him for a second that he had looked around, thinking he must have walked straight into the point of a knife.

Looking at the girl in the attic window was like looking into Kevin Donnell’s house, but without the pain.

And at that moment Will vowed that he would never let anything bad happen to the girl in the window. The idea was immediate and deadly serious; he could not let anything bad happen to her. He had some vague idea that it would be terrible for himself.

Church bells boomed out suddenly, shattering the silence, and Will jumped. Two o’clock in the morning already! He had been gone from the alchemist’s for more than an hour, and he had yet to complete the tasks he had been sent out to perform.

“Go straight to the Lady Premiere,” the alchemist had said, pressing the wooden box into Will’s arms. “Do not stop for anyone. Hurry right there, and give this to her. Do not let anyone else see it or touch it. You are carrying great magic with you! Huge magic. The biggest I have ever made. The biggest I have ever attempted.”

Will had stifled a yawn and tried to look serious. Every time the alchemist made a new potion, he said it was his greatest yet, and Will had difficulty being impressed by the words nowadays.

The alchemist, perhaps sensing this, had muttered, “Useless,” under his breath. Then, frowning, he had given Will a handwritten list of items to collect from Mr. Gray, after the delivery was complete.

And now it was two o’clock, and Will had neither seen the Lady Premiere nor visited Mr. Gray at his work space.

Will made a sudden decision. The Lady Premiere lived all the way on the other side of the city, near the alchemist’s shop, while the gray man was no more than a few blocks away from where he was standing. If he delivered the magic first, he would have to cross the whole city, then cross back, then cross back again, and he would not be home in time to sleep more than an hour. Really, he should not have come to see the girl in the window; it was absurd. But he could not feel even a little bit bad about it. In fact he felt better than he had in days.

No. He would go to Mr. Gray first and then deliver the magic to the Lady on his way back to the shop, and the alchemist would never know the difference. Besides—Will shifted the box again—the potion was no doubt an everyday kind of magic dust, for curing warts or growing hair or keeping memories longer or something like that.

Will dug into his pocket and pulled out the crumpled list the alchemist had scrawled hastily on a scrap of paper. Nothing too unusual: a dead man’s beard, some fingernail clippings, two chicken heads, the eye of a blind frog.

Yes, Will decided, casting one last look at the girl in the window before setting off. Groceries first; and after that, the magic.

Up in her room, Liesl drew a train with wings, floating through the sky.

AT THE END OF A TINY, WINDY STREET AND DOWN

a steep flight of narrow wooden stairs and past a sign that said

THE ATELIER OF GRAY.

BODY DISPOSAL, CORPSES,

ANIMAL AND HUMAN PARTS (SINCE 1885)

,

Mr. Gray was feeling very annoyed.

For the fourth time in two weeks, Mr. Gray was completely and entirely out of urns.

The problem was how rapidly people were dying. If they would just stop dying, stop even for a week to give his urn maker and his casket maker time to catch up . . .

He stroked his chin thoughtfully. Perhaps he could request that the mayor order that there be no deaths for a week? Or impose a death tax? He shook his head. No, no, impossible.

He knew enough about death to know that it could not be bribed, bought, delayed, or put off. He had lived in the cold basement rooms beneath the funeral home of his great-great-great-grandfather for his whole life. As a child he had played with the loosened gold teeth of the dead men, spinning them across the floor like tops and watching them catch the light. He had been a gravestone maker and a gravedigger, an executioner for the state, a mercy killer, a mummifier.

These days he mostly stuck to the simple stuff: burning and burying. When someone died, he either put the body in a nice wood coffin lined with sober black silk, or he put the body headfirst in the oven and, when it had burned away to ashes, placed these in a nice decorative urn, which could be kept neatly on display on a mantel or a shelf or a bedside table. Mr. Gray’s great-uncle, for example, was kept within Urn Style #27 (Grecian) just above the stove in the kitchen; his mother was in Urn Style #4 (Lavish) on the windowsill overlooking the street, and his father, in Urn Style #12 (Sober), was sitting next to her. Mr. Gray liked to have his family all around him.

Of course, he still did a little bit of dealing on the side—odds and ends, bits and pieces, toes and fingernails, animal blood, this and that. These were the scraps that a nighttime business, a business of death, was built on, and Mr. Gray was only happy to pass along the dried and dead and shriveled things, the squirmy and wormy things, the rot, that came his way.

He shook his head and began rummaging under the kitchen sink for an empty container to hold the mortal remains of a certain John C. Smith, bar owner, who had arrived at his door that morning.

Only three days ago he had been forced to sacrifice his mother’s old wooden jewelry box in the service of his profession. It was sitting on the kitchen table now, full of ash. He had regretted using the jewelry box for such a purpose, but he could not very well send the widowed Mrs. Morbower home with a cereal box containing her dead husband, as he had done earlier in the week with Mrs. Kittle. . . . Not after Mrs. Morbower had paid him so well and so quickly to have the body burned to ash. . . .

Mr. Gray sighed. If people would only stop dying. Just for a week! He was sure a week was all he needed. . . .

Tap-tap-tap.

A soft knocking shook Mr. Gray from his reverie. He went to the door of his atelier and looked through the grimy window to the narrow street. He saw nothing but a patch of black hair sprouting at the very bottom of the window. The alchemist’s boy: Billy or Michael or something-or-other, Mr. Gray could never remember. All children were the same to him: strange and sticky and best avoided, like an upright variety of jellyfish.

But he opened the door.

“Hello,” Will said nervously, as Mr. Gray loomed before him. He shifted the box of magic in his arms—his left arm had started to cramp, from holding the wooden box for so long—and handed Mr. Gray the list the alchemist had written for him. “Here for a pickup, please.”

Mr. Gray’s long, thin face grew even longer and thinner as he scanned the list. “Come in,” he said finally, and stepped backward so Will could pass through the door.

The smell hit Will as soon as he entered the small front room that served as Mr. Gray’s kitchen, work space, and receiving room. No matter how many times he came for a pickup, Will could never get used to it: a bitter, scorching smell mixed with the smell of bodies, like a fire lit in the very center of a dirty stable. He pretended to scratch his nose, and he breathed into the fabric of his coat sleeve.

Mr. Gray didn’t seem to notice. He was still reviewing the alchemist’s list, muttering things like, “Yes, fine, okay” or “Well, I’m not sure about two chicken heads” or “A dead man’s beard? I might have a mustache somewhere.”

Finally Mr. Gray looked up, stroking his chin. “You may as well sit,” he said. “This might take a little while.”

“Thank you.” Will did not really want to sit at Mr. Gray’s table, which was cluttered with mysterious jars of things and various foul-smelling chemicals, but he did as he was told because he had always been slightly afraid of Mr. Gray and did not want to anger him. He placed the wooden box of magic on the table, next to another wooden box that looked relatively plain but probably (Will knew) contained chicken hearts or something equally nasty, and sat down. It was, at least, a relief to be off his feet.