Life Class: The Selected Memoirs Of Diana Athill (14 page)

Read Life Class: The Selected Memoirs Of Diana Athill Online

Authors: Diana Athill

Much of this feeling about courage was derived from Geoffrey Salmond, husband of my mother’s eldest sister Peggy and father of Joyce, Anne, Pen and John. He was the uncle who ended in the RAF – indeed as head of it. When he was a dashing and amusing young army officer he, with his brother Jack and a small group of friends, became enamoured of that fascinating invention the flying machine, which at that stage appeared to be put together of cardboard and string. They were among the first Englishmen to fly, first as amateurs, soon afterwards as members of the Royal Flying Corps, which they got going. Early in the First World War Geoff played an important part in persuading the War Office that airborne men would be invaluable at finding out what was going on behind the enemy’s lines – he was one of the Flying Corps thinkers, as well as a daring pilot. After the war he made the first ever flight across the Himalayas, when navigation was a matter of peering earthwards and following rivers and (when there were any) roads. He also became the commander of the RAF in India, and contributed a good deal to the development of civil aviation.

His adoring wife understood from the beginning that on no account must she betray how much she feared for him when he was flying: if you were married to a hero it was your duty to be heroic too, and never to burden him with an image of yourself being unhappy for fear of losing him. She played her part to perfection: all their lives her daughters would remember how proudly their father told them that she was ‘as brave as a lion’.

She was to need this courage, poor Aunt Peggy. First Geoff died of bone cancer when he was only middle-aged, then their son John, who had followed his father into the RAF, was killed in the Second World War. I did not see her under the immediate impact of these two terrible blows, but I know what got her through them: the conviction that to give way would be unworthy of Geoffrey Salmond’s wife. She and her daughters, although they never spoke of it, were always thereafter to have about them a faint aura of dedication to an inspiring memory. They were examples of the valuable aspect of that Good Behaviour so well understood by the novelist Molly Keane.

It is an ideal that can, of course, be damaging. Once, when my mother was eighty, the husband of a good friend of hers died suddenly, and when I arrived for a weekend two days later she told me about it with feeling, knowing how deeply her friend would feel her loss. I said ‘Oh God, I must call her’; and when I had done so my mother muttered in a shamefaced way ‘How brave you are.’ – ‘Brave?’ – ‘She might have cried.’ It turned out that she had not yet dared to get in touch with her friend: a fear of raw emotion that can cripple human responses, as well as support endurance.

When we were children there were, of course, no undercurrents to being brave. It was just a stylish way to behave, at which the Salmonds were a good deal better than I was. I was well aware that if we were faced with a really hairy jump in cold blood, Pen would be much readier than I to put her pony at it; anyone could be brave out hunting because of the excitement, but she was always brave. From time to time it worried me: in a situation which required real heroism – if someone was drowning in a turbulent river, perhaps, or trapped in a burning house – would I be able to rise to the occasion? It didn’t feel likely, but on the other hand it was possible that nobody felt it likely – that given such a situation you responded in the right way either automatically, or because you were so frightened of what people would think if you didn’t that doing it was the lesser evil. I could only hope …

We knew the Bible well – or rather, those parts of it read to us by Gran, starting when we were very young: Joseph and his brethren, Samson and Delilah, David and Jonathan, Samuel and Eli, Christ walking on the water, the miracle of the loaves and fishes, and of course the story of Jesus’s birth. Gran read or told those stories as though they were about real events which were parts of everyone’s knowledge and life. She loved most of the books she read to us, but she loved the Bible best: the Old Testament stories, particularly, she told with contained relish. She introduced us to poetry only through narrative verse, chiefly Macaulay’s and Scott’s, but it was to poetry more broadly speaking that she led us through the Bible, by the vibration of her response to it. To poetry, rather than to morality, in that it made little impression as a source of a sense of right and wrong.

My grandparents were sensible and modest people, so I doubt that either of them would have presumed to claim that he or she was a

good

Christian, but equally I am sure neither of them doubted that Christians they were. They were regular churchgoers; they respected the Sacraments; they obeyed the Ten Commandments; they felt strongly – even passionately – that faith should be drawn as directly as possible from the Bible without the intervention of a priesthood (hence their detestation of Roman Catholics). But if they actually

believed

in the Incarnation, which I take to be Christianity’s central tenet, their conduct concealed the fact. It seemed much more like the conduct of people moved by common sense combined with an ideal of gentlemanly behaviour than it did like the conduct of people seeking communion with God.

What people like them would have said in response to such a thought was that a person’s beliefs – his really important, inner beliefs – were a matter between himself and God, too important to be lightly exposed. About which I feel doubtful. It seems to me more likely that what could not be lightly exposed was a person’s really important inner disbelief.

As far as I was concerned, they gave me an extraordinarily undemanding God. It was His love and His understanding that were emphasized, so much so that I found it cheering, not alarming, to remember that He knew everything about me: every thought, every motive, every illegitimate desire. Because He knew every single thing, and understood it, then He knew the strength of temptations and how, considering my frailty, I didn’t do too badly against them. People might misunderstand, He wouldn’t. Whatever tensions there were (and there were some), the bedrock of trust had not been cracked: what I expected from life and from God was love, forgiveness and protection. I was threatened only if naughty or silly, and then, however resentful I might feel at the moment, I knew well enough that it was my own fault, and I needed to call on no great moral energy to accept that fact. This was because most of the sins committed by me and the other children didn’t matter very much to anyone and certainly not to God. The only sin taken really seriously was the one which, if you brought it off successfully, would make nonsense of adult control: lying.

The dreadfulness of lying was brought home to me when I was four years old. All the family’s children were at a tea party in a neighbour’s garden, where there was a cherry tree trained against a wall: overwhelmingly tempting because cherries were rare in our county and their smooth redness was so perfect. They were, in fact, the bitter kind grown for jam-making, but I was unaware of that as I gazed longingly, feeling in anticipation the protective net’s fine thread as I pushed fingers through it, the slight harshness of the leaves, the plumpness of the fruit. I didn’t dare, though. This was Cousin Minnie’s garden, not ours, and she was proud of her cherries. But I was hand in hand with my cousin Anne, four years my senior, who was showing me how to play hide-and-seek properly, and who was touched by my expression. ‘We oughtn’t to,’ she said – and then, generously: ‘Look,

I

mustn’t because I know that it’s wrong, but

you

can have just one.’ So I took the cherry she picked for me, bit into it, let it drop because of its unexpected sharpness, clutched at it – and squashed it against the front of my frock. There in the middle of my stomach was a large red stain, advertising my theft for all the world to see.

My consternation was so great that I didn’t howl, only stared appalled at my cousin. Hers was even greater. She was a redhead of remarkable untidiness, her socks always wrinkled round her ankles, her bloomers always showing under her skirt, always longing to do right and ending by doing wrong. A clown and a tragedienne, she laughed and cried with abandon, loved to act and to tell stories, rejoiced in ideas of nobility, self-sacrifice and daring. The person she would most have liked to have been was the Boy who Stood on the Burning Deck – a poem which she often declaimed. She was adored by us, the younger ones, because of her loving kindness and her entertainment value; and now I knew at once that she would shoulder the responsibility for my sin.

And sure enough, ‘Don’t cry,’ she said. ‘It’s all my fault and I know what we’ll do. We’ll run home very quickly and I’ll wash your dress, and by the time they all get back they won’t be able to see any stain and no one will know.’

It was easy to leave the garden by a back way without anyone seeing, and then we only had to cross a lane to be in the park of my grandparents’ house. ‘Faster, faster!’ cried Anne, becoming the Red Queen, and I was whirled along like Alice in the picture. Anne had an inkling that the disappearance of two members of the tea party, one of them only four, would cause alarm. I didn’t think of this or anything else, having simply become part of a situation compounded of urgency and secrecy out of which I was about to be miraculously delivered. We covered half a mile of park and garden at high speed, pausing sometimes to gasp and clutch at the stitches in our sides, crept up to and into the house, and bolted into a bathroom. ‘Quick, quick, undress – look, I’ll run the bath – if they come I’ll say I’m giving you your bath and it won’t be a lie because you’ll be in it.’

No sooner was I in the bath and the stained frock in the hand-basin than there came a rattling at the door. ‘Are you in there?’ ‘What are you doing? Open the door at once – what are you

doing

?’ My mother’s voice was agitated – the adults had had time to suppose that the older child had fled in panic at some disaster overtaking the younger one. The bedraggled frock came out of the basin with the stain still there – it was no good saying ‘I’m giving her her bath’ with the evidence glaring. Anne had one last inspiration: ‘Sh!’ she whispered, ‘I’ll pretend I’m going to the lav,’ and she whipped down her knickers, sat on the pan and began to grunt with conscientious realism. I sat in the chilly water (there had been no time to adjust the temperature), as quiet as a mouse, overcome by the daring of this last device, and still trusting my protector’s ingenuity.

‘I

know

you aren’t just going to the lavatory,’ cried my mother (how? What hope against these guilt-detecting eyes which would see through doors?); ‘Let me in AT ONCE!’ And when the door was opened at last and the tearful confession had been made, it turned out – and this was amazing – that stealing the cherry hadn’t been a sin at all, nor even had staining the dress. It was, explained my mother,

the lie

that had been so very wrong. But I had never

said

I hadn’t stolen the cherry – surely lies were

words

? But no: it appeared that a lie could be something as complex and exhausting as running all the way across the park and sneaking into the house and pretending to have a bath. It was a cheering thought, once absorbed, because it proved that hiding sins was much more trouble than admitting them; and I have never since then been much of a liar. Excepting on those very rare occasions when the absolute necessity for it has been so overwhelming that it didn’t feel like lying at all.

Which must, I suppose, have been the case with my grandfather – the apparently impeccable source of his household’s wholesome atmosphere – when his only son, while still an undergraduate at Oxford, announced that he wished to become engaged to a young woman who was a Roman Catholic. This comic recurrence of crisis at Oxford, which seems to have become almost a tradition, was something that none of us knew about until recently, when it turned up in another old suitcase crammed with letters kept by my grandmother.

My grandparents had never met the young woman, who lived in the north of England with her aunt – perhaps she was an orphan. How my uncle met her is not revealed, but they had known each other well for two years: this is stated in the first of the letters, from the young woman’s aunt to my grandfather, which protests in courteous and reasonable terms at his forbidding the engagement without ever having met her niece. She says that the two young people know each other well, that the attachment between them is sincere, and that her niece is a good and sensible girl as well as a charming one, and does not deserve a dismissal so sudden and cruel. She goes on to say that while she agrees with him in theory that it is best if husband and wife are of the same faith, she must point out that she herself is a Protestant who has been married to a Roman Catholic for thirty years without any problems, so she can assure him from her own experience, as well as that of other couples of her acquaintance, that a ‘mixed marriage’ is not by any means necessarily disastrous. She is not asking – she says – that he reverse his decision at once, but she does feel that it would be only fair for him and his wife to meet her niece before finally forbidding the engagement.

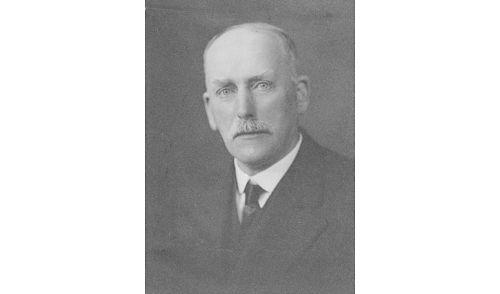

William Greenwood Carr: ‘Gramps

’