Life in a Medieval Village (4 page)

Read Life in a Medieval Village Online

Authors: Frances Gies

Roofs were thatched, as from ancient times, with straw, broom or heather, or in marsh country reeds or rushes (as at Elton). Thatched roofs had formidable drawbacks; they rotted from alternations of wet and dry, and harbored a menagerie of mice, rats, hornets, wasps, spiders, and birds; and above all they caught fire. Yet even in London they prevailed. Simon de Montfort, rebelling against the king, is said to have meditated setting fire to the city by releasing an air force of chickens with flaming brands attached.

24

Irresistibly cheap and easy to make, the thatched roof overwhelmingly predominated century after century atop the houses and cottages of medieval peasants and townsmen everywhere.

25

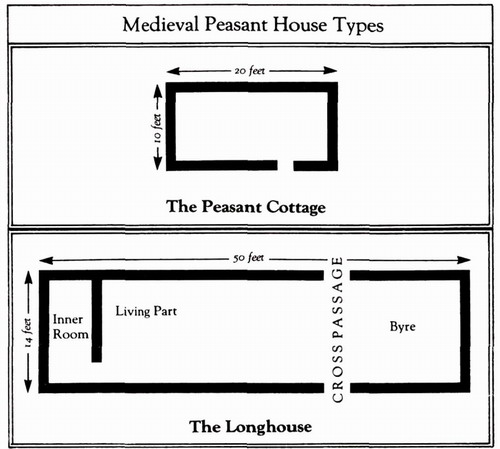

Some village houses were fairly large, forty to fifty feet long by ten to fifteen wide, others were tiny cottages.

26

All were insubstantial. “House breaking” by burglars was literal. Coroners’ records speak of intruders smashing their way through the walls of houses “with a plowshare” or “with a coulter.”

27

In the Elton manorial court, a villager was accused of carrying away “the doorposts of the house” of a neighbor;

28

an angry heir, still a minor, “tore up and carried away” a house on his deceased father’s property and was “commanded to restore it.”

29

Most village houses had a yard and a garden: a smaller “toft” fronting on the street and occupied by the house and its outbuildings, and a larger “croft” in the rear. The toft was usually surrounded by a fence or a ditch to keep in the animals whose pens it contained, along with barns or storage sheds for grain and fodder.

30

Missing was a privy. Sanitary arrangements seem to have consisted of a latrine trench or merely the tradition later recorded as retiring to “a bowshot from the house.”

31

Drainage was assisted by ditches running through the yards.

Private wells existed in some villages, but a communal village well was more usual. That Elton had one is indicated by a family named “atte Well.” Livestock grazed in the tofts—a cow or an ox, pigs, and chickens. Many villagers owned sheep, but they were not kept in the toft. In summer and fall, they were driven out into the marsh to graze, and in winter they were penned in the manor fold so that the lord could profit from their valuable manure. The richer villagers had manure piles, accumulated from their other animals; two villagers were fined when their dung heaps impinged “on the common highway, to the common harm,” and another paid threepence for license to place his on the common next to his house. The croft, stretching back from the toft, was a large garden of half an acre or so, cultivated by spade—“by foot,” as the villagers termed it.

32

Snow highlights house sites, crofts behind them, and surrounding fields in aerial photograph of deserted village of Wharram Percy. Upper left, modern manor house, with ruined church behind it. Cambridge University Collection of Air Photographs.

Clustered at the end of the street in Nether End, near the river, were the small village green, the manor house, and the mill complex. An eighteenth-century mill today stands on the spot where in the thirteenth century “the dam mill,” the “middle mill,” and the “small mill” probably stood over the Nene, apparently under a single roof: “the house between the two mills” was repaired in 1296.

33

The foundations were of stone, the buildings themselves of timber, with a thatched roof, a courtyard, and a vegetable garden.

34

A millpond furnished power to the three oaken waterwheels.

35

Grass and willows grew all around the pond, the grass sold for fodder, the willow wands for building material.

36

Back from the river stood the manor house and its “curia” (court), with outbuildings and installations. The curia occupied

an acre and a half of land,

37

enclosed with a wall or possibly a fence of stakes and woven rods. Some manor houses had moats to keep livestock in and wild animals out; the excavations of 1977 at Elton revealed traces of such a moat on the side toward the river. An entry gate led to the house or hall

(aula),

built of stone, with a slate roof.

38

Manor houses were sometimes constructed over a ground-level undercroft, used for storage. The Elton manorial accounts also mention a sleeping chamber, which had to be “pointed and mended” at the same time as the wooden, slate-roofed chapel adjacent to the hall.

39

Kitchen and bakehouse were in separate buildings nearby, and a granary was built up against the hall.

40

The manorial accounts mention repairs to a “communal privy,” probably restricted to the manorial personnel.

41

Elsewhere on the grounds, which accommodated a garden and an apple orchard, stood a stone dairy, equipped with cheese presses, settling pans, strainers, earthenware jars, and churns.

42

The “little barn” and the “big barn” were of timber, with thatched roofs; here mows of

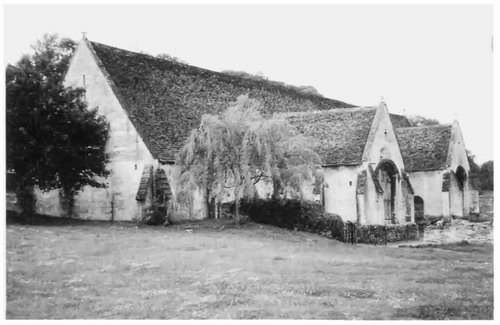

Abbey barn, c. 1340, storehouse for the home manor of Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset).

Tithe barn, for tithes paid in grain, Bradford-on-Avon, with fourteen bays, two of them projecting into porches.

grain were stored. The big barn had a slate-roofed porch on one side protecting a great door that locked with a key, and a small door opposite. The door of the little barn was secured by a bolt.

43

Under a thatched roof, the stone stable housed horses, oxen, and cows, as well as carts, tools, and harness.

44

A wooden sheepfold, also thatched, large enough to accommodate the lord’s sheep and those of the villagers, was lighted with candles and an oil lamp every spring at lambing time.

45

Still other buildings included a kiln for drying malt

46

and a pound—a “punfold” or “pinfold”—for stray animals.

47

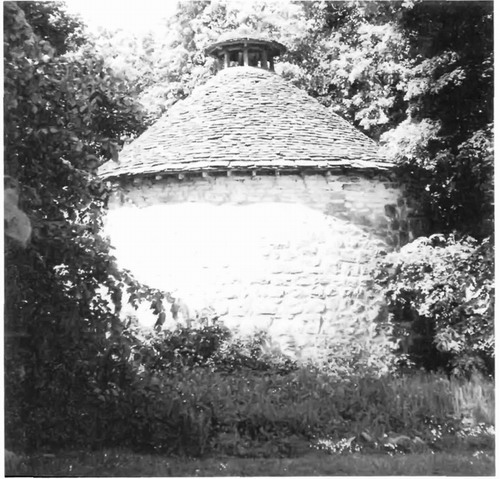

Two large wooden thatched dovecotes sheltered several hundred doves, sold at market or forwarded to the abbot’s table.

48

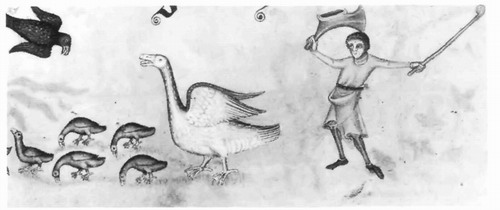

Among other resident poultry were chickens and geese, and, at least in one year’s accounts, peacocks and swans.

49

On its waterfront, the manor possessed several boats, whose repairs were recorded at intervals.

50

Across the street from the curia stood one of a pair of communal ovens to which the villagers were obliged to bring their

bread; the other stood in Overend. The ovens were leased from the lord by a baker. A forge was leased by a smith who worked for both the lord and the tenants.

51

The green, whose presence is attested by the name of a village family, “atte Grene,” could not have been large enough to serve as a pasture. Its only known use was as a location for the stocks, where village wrongdoers were sometimes held.

At the opposite end of the village, in Overend, stood the parish church, on the site of earlier structures dating at least to the tenth century. The records make no mention of the rectory, which the enclosure map of 1784 locates in Nether End.

South of the church in Overend lay the tract of land on which two hundred years later Elton Hall was built. In the thirteenth

Medieval dovecote, Avebury (Wiltshire).

Dovecote. Bodleian Library, Ms. Bodl. 764, f. 80.

century, this was a sub-manor of Elton, a hide of land held by a wealthy free man, John of Elton, who had tenants of his own.

A medieval village did not consist merely of its buildings. It

Man driving geese out of the grain with horn and stick. British Library, Luttrell Psalter, Ms. Add. 42130, f. 69v.