Like Father

Authors: Nick Gifford

- 1 Like Son

- 2 Reminders

- 3 Dear Diary

- 4 Cassie

- 5 The start of it all

- 6 Two telephone calls

- 7 What Parents Do

- 8 Little Rick

- 9 Normal

- 10 Spirit Talk

- 11 Opening up

- 12 Hodeken

- 13 Berlin, August 1961

- 14 Voices...

- 15 Talking

- 16 Keeping it together

- 17 Gather and share

- 18 A little word in your ear, Danny

- 19 Open Day

- 20 On the cards

- 21 A telephone call and a visit

- 22 A dark and stormy night

- 23 Hinzelmannchen

- 24 Normal again

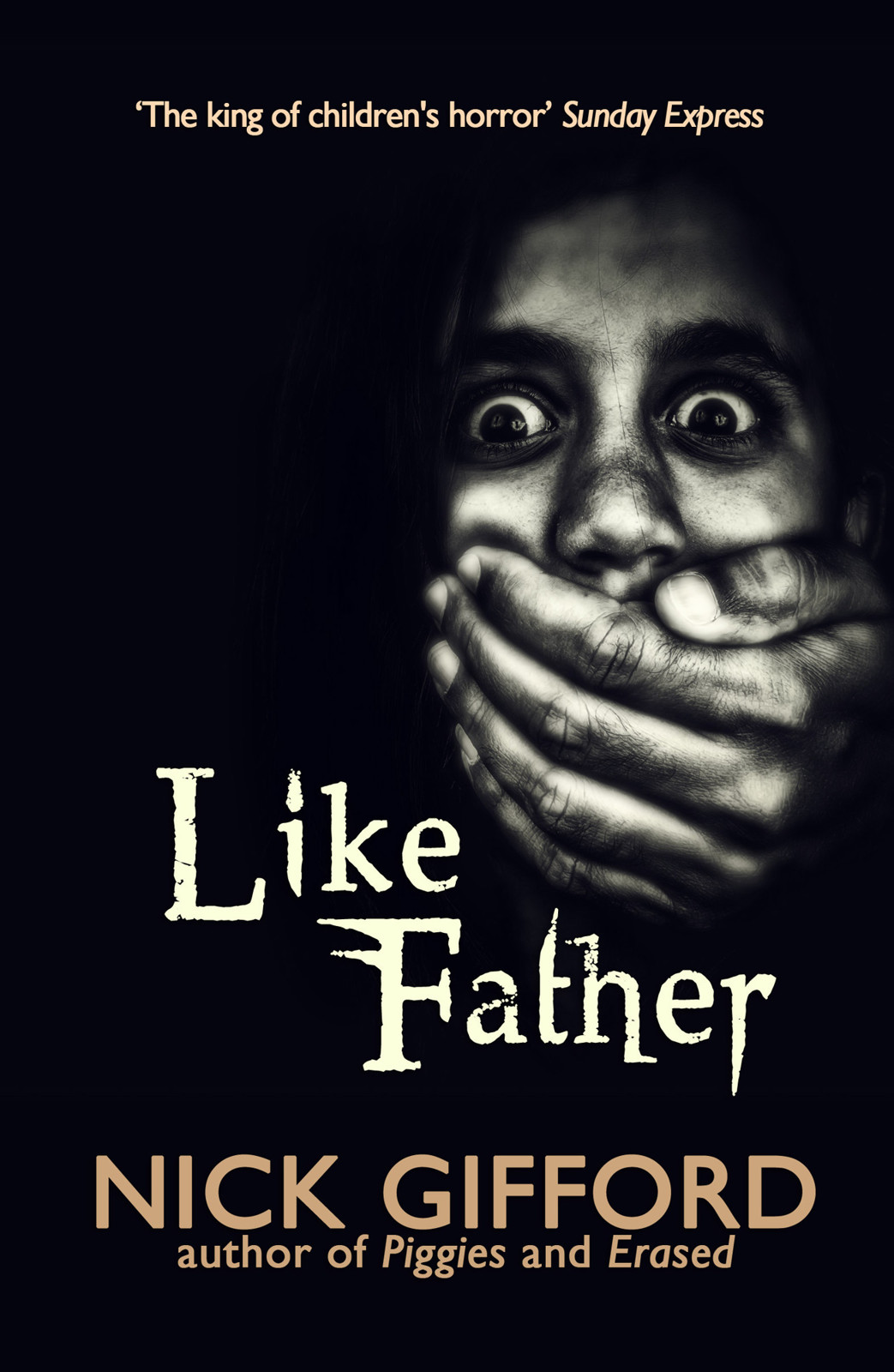

Like Father

NICK GIFFORD

infinite press

Like Father

Voices in my head. It's driving me mad. It's like my skull's splitting open from the inside. They're talking to me. Laughing at me. Telling me what to do. I'll have their tongues. That'll shut them up.

Danny is terrified of being like his father. His dad ended up in prison after a night of savage violence.

But then he finds his father's diary and uncovers his dark thoughts - and even darker secrets. Who was whispering to his father, goading him, leading him on?

And what if they are coming back for Danny?

"The king of children's horror..."

Sunday Express

Copyright © 2005, 2013 Nick Gifford

Cover © Kamira

All rights reserved.

Originally published by Puffin as

Incubus

, this edition reverts to the author’s preferred title.

Published by infinite press

www.nickgifford.co.uk/

Follow @TheNickGifford on Twitter

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

The moral right of Nick Gifford to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

ISBN: 9781310639470

Electronic Version by Baen Books

1 Like Son

“Do you not see it, Danny? You think my eyes have gone just because I’m 74 and I take my teeth out every night?” Oma Schmidt cackled and rubbed at the damp corner of her mouth with the cuff of her cardigan.

Danny Smith took the photo from her and stared at it, holding it steady as the train juddered and rolled.

Each time they visited Danny’s father, she had to do something like this. Find something to bring. It might be a photo, or an old magazine, or once even an item of clothing, an old jumper. Something from the past, from when things had been so much better. Something to comfort her, and maybe she thought it would comfort her grandson, Danny, too.

“You tell me I’m wrong?” she demanded.

No, he saw it.

The photograph was creased, the corners curled and thickened where the layers were coming apart. The colours were faded as if they were being washed away.

A boy stared out of the picture. He sat on what was probably a brand new bicycle. A large child on a bike that was too small, but the boy was still grinning. Proud. His long, frizzy hair was cut short at the front and on top, and he wore flared trousers and a jumper with multi-coloured horizontal bars down the front. The bike was an ugly-looking thing: small wheels with thick tyres, long handlebars sticking up and then bent down at each end, an extended saddle with a back-rest thrust upwards at right-angles.

He saw it all right.

It was in the eyes. Eyes that stared back at him from the bathroom mirror each morning when he washed.

The boy in the photo was about fourteen, the same age that Danny was now. Like the boy in the photo, he was tall and awkward, in a body that somehow seemed too big and angular for him. The boy in the photo, sitting proudly on his new Chopper bike, was Danny’s father and, stupid 1970s haircut and clothes aside, he looked just like Danny.

“You could be twins, eh?” said Oma, nudging Danny sharply with a bony elbow. “You are so alike.”

Danny looked away, out of the window. He stared at the graffiti on the walls and buildings they were passing. He was not like his father.

He was

not

like his father.

He still had the photo. He wanted to tear it up into little pieces and throw them out of the window, watch the shower of photograph-confetti spreading over the tracks, being left safely far behind.

He was not like his father.

He had self-control.

He looked down and saw that his knuckles were white where he gripped the photograph. He made himself relax, and handed the snap back to his grandmother.

“They won’t let you take it in,” he told her. They weren’t allowed to take things into the visiting hall. “They’ll make you leave it in your bag in one of the lockers.”

She smiled and tapped the side of her head. “I have it up here,” she said. “That is what matters.”

~

Prison was the same as it ever was.

They arrived just behind a woman with three young children. While the guard checked her papers at the gate, she stubbed her cigarette out on the wall and then put the butt back in her bag for later.

Danny handed over the Visiting Order and their IDs: his birth certificate and Oma’s pension book. He filled in a form with their names and address and the guard gave them a ticket with a number on. Danny was too young to visit on his own, and had to be accompanied by an adult. In reality, though, he could have coped easily enough. It was Oma who needed looking after.

They were early, so they sat in the Visitors’ Centre, which as usual was full of women and rampaging children. Oma sat humming one of her tunes to herself. She didn’t seem aware of the surroundings. She was going to see her son again. That was all that mattered, and she was happy because of it.

Danny sat with her for a time, then went and looked at some leaflets.

Talking to Children about Imprisonment

. He recognised that one. He skimmed through it.

“It is important that they do not see them as a bad person, even if they did do something wrong...”

Ha! That was his favourite line in that one. But what if the prisoner really

is

a bad person?

He put the leaflet back and went to sit with Oma again. He calmed his breathing, trying to remember some of the relaxation techniques he had been taught.

“Seventy-three.”

He looked at the ticket. That was their number. “That’s us, Oma,” he said, interrupting her happy daydream.

They went through to the next room. Danny handed over his wallet, his keys and his coat to be stored in a locker. All he kept was some loose change for the drinks machine inside. He kicked off his shoes for them to examine, and took off his hooded sweatshirt so that one of the guards could pat him down and check his pockets.

By his side, Oma had to go through the same routine, smiling all the time at the rather uncomfortable-looking female prison officer who was removing the old tissues and sweets from her pockets. Shoes and sweatshirt back on, Danny led Oma through the metal detector and past the sniffer dog and its handler.

They emerged in a hall with about thirty small tables arranged with chairs to either side. About half of them were occupied and most already had visitors. The prisoners who didn’t all turned expectantly to look at Danny and Oma, then looked away again. Not the people they were expecting. Not

their

visitors.

These men... they were murderers, rapists, drug-dealers, men of violence and brutality and yet... the look of lost hopes on their faces when they saw that the latest visitor was not their own made them seem just like ordinary people.

One face didn’t turn away.

One prisoner met Danny’s eyes briefly, and then Oma’s, a smile breaking out nervously, uncertainly. The 1970s haircut was gone, the hair short, and thin on top. The features were rounder. Where he had been gangly and awkward in the photo, Danny’s father had long-since grown into his big frame.

He nodded and waved them towards the chairs at his little table, as if they might head elsewhere if he didn’t actually invite them to join him.

“Mum,” he said, taking Oma’s hand across the table. “Daniel.” Smiling more comfortably now, nodding, excited. “It’s been a long time. I didn’t know if you’d make it.”

“My boy,” said Oma. “It is hard since she moved us back of the beyond. Is a long journey on the train and then the bus. Is much for the boy.”

Danny and his father exchanged a look, both smiling at Oma’s good-natured grumbling.

It was so easy to forget at times. Despite the guards, the wailing babies and over-excited children, the ever-present low buzz of urgent conversation. Just briefly, every so often, Danny and his father could exchange a look, a few words, and they were just father and son. All so natural.

And then: this was his father, sitting here in his badly-fitting prison uniform. It sometimes seemed that there had been an awful mistake.

But Danny knew there had been no mistake.

This place was where his father belonged.

“How is she?” said his father now. No need to explain the “she” he referred to. It was Val – his wife, Danny’s mother, the “she” who had moved Danny and Oma away from London when the stresses of trying to live where everyone knew what had happened had become too great. Danny’s mother had moved them out to the Hope Springs Trust, a centre for alternative living that had grown up around an old school in the west country.

“She’s fine,” said Danny. “Teaching more classes at the Trust. Helping them sort their accounts out after the last audit. They don’t know what’s hit them.”

That was the thing about visiting, Danny thought. You visit so that you can talk and so that’s what you do: you actually talk. He couldn’t remember talking to his father very much ...

before

. But now, when they only saw each other so infrequently, they made good use of the time.

“How’s your course going?” Danny asked. His father was studying psychology with the Open University. They talked about the course, about the monotony of the daily prison routine, about some of the people his father was doing time with. They talked about Danny, too. About school and the flat, about TV and music and what it was like living in Wishbourne now that they had settled in. The hands on the big wall clock seemed to keep jumping forwards as they talked, time swallowing itself up far too quickly.

“My boy,” said Oma at one point. She hardly spoke on these visits. She always seemed happy just to be in the presence of her son. “Are they looking after you, heh? Are they feeding you well?”

“Mother, their hospitality never fails. I think I will stay on here for a while.”

Oma looked down sharply at this, and then away, her eyes following the movements of a little boy who was playing with a squeaky hammer in a corner of the hall which was set up as a toddlers’ play area.

“Dad, we found something a few days ago.”

His father raised an eyebrow, waiting for Danny to continue.

“A journal. A black-covered, hardback book. The dates in it start in December 2000 and run out in ... a few months later. It was in a box from the move. There’s still loads of stuff we haven’t unpacked from then, even now.”

His father shrugged. “What is it? Have you read it?”

“I ... only a little. It’s yours. Your writing. It says about what happened. About what you were thinking.”

It was his father’s turn to look down now. After a long silence he said, “What I was thinking? That’s not somewhere I want to go. Not ever again. My writing, you say? I don’t remember writing a diary.”

He didn’t remember much of anything, though. Not that he would tell them at his trial. Not that he would ever tell anyone since.

“I just thought you should know that we’d found it,” said Danny softly.

“If you think it’s important you could send it to Justin Peters.”

Peters had defended Danny’s father at the trial. Danny nodded. It was reassuring to have something to do with the thing.

“Oma had a photo of you on a Chopper,” said Danny, forcing brightness into his voice. On the train the picture had been something to torment him, but now it suddenly seemed different. A treasure from the past, something to make them think, and talk, of better times.

Oma reached into the folds of her skirt and moments later she produced the battered old photograph. “The lady let me bring it in,” she said, beaming.

“Oh boy, that bike!” His father picked up the photo, his hand shaking.

This was one of those moments. Those brief instants when the surroundings melted away and they could have been anywhere, just grandmother, father and son together. Danny squeezed his eyes shut. He knew it couldn’t last.

~

Back home at Hope Springs, late that night, Danny pushed his bedroom door shut and leaned with his back against it.

The room was dark, lit only by the moonlight through the window. Strange shadows, at strange angles, filled the room, the light blue and cold.

He closed his eyes and tried to calm his ragged breathing.

He went and dropped belly-down on the bed, face in the pillow so he could barely breathe.

The rage was there, in his belly and in his chest, struggling to burst free. Out in the real world he could control it. That’s what he

did

. But here in his room, the door shut, the world at sleep ... sometimes he just had to let it out.

He punched the pillow with the base of his fist, right next to his head. Punched it again, harder this time.

His father. That place.

His mother and her brisk efficiency. The way she shut out everything and had never, not once, spoken about the things that really mattered.

He remembered faces all around him. People taunting him, calling him names – people who had been his friends. And the looks, or rather, the looking away as soon as eye contact had been made.

All of them.

His hand hurt, he was hitting the pillow so hard. The skin stung with friction burns.

Music. Out in the hallway.

It was Oma, humming one of her old German folk-tunes. Calming sounds. She always knew.

He stopped thumping the bed. He slid his hand under his belly, now fully aware of the pain. He turned his face on one side, away from the damp patch where he had been sobbing, and stared out at the dark shapes of the trees.

Soon he was asleep.