Lilla's Feast (47 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

“I really hope that if the book can do anything it is to show that you can turn your life around,” she says, pushing back the same red hair that has traveled down three generations from Lilla’s first husband. “And that is sort of what happened to me. She inspired me, as well as giving me the means to do it myself. I could have missed my chance. Instead, it’s given me a whole new life.” Frances now lives in Notting Hill and Cheshire. A few days after we meet, she is off to Africa in pursuit of the subject of her second book.

I ask her the question she has been fearing. She looks bashful. “I cook a little,” she says, turning her fork. “I like to hang about the Aga in Cheshire, although my husband does wonder when this angel of domesticity is coming his way. But a friend of mine said that if I could write about cooking as I do in the book, then I must at least be a cook at heart, if not at the stove.”

Lilla, who loved her food like no other, would not have minded a bit. Her cookery book, full of chapters on soups, fish, and game, now sits in the Imperial War Museum. That was her great achievement. Her great-granddaughter Frances’s book is now on bookshelves all over this town and thousands of others, and that is hers.

Lilla’s War with China

BY FRANCES OSBORNE

Little old ladies with bottles of ink, mounds of writing paper, and firm hands have long been the bane of government officials. There’s even a name for them: “Angry of Tunbridge Wells.” My great-grandmother Lilla, whom I remember living in that venerable Kentish town, was Super-Angry. She was so angry that at the age of one hundred, after an extraordinary exchange of correspondence lasting thirty years and consuming many sheets of Basildon Bond, she succeeded in extracting a check from none other than the Communist government of China. And when I was writing

Lilla’s Feast,

the story of her remarkable life, I discovered how she did it.

Lilla had long been tough. In the 1930s she ran two businesses in a colonial trading port in China called Chefoo. When the Japanese half starved her in a concentration camp during the Second World War, she defiantly spent her three years of imprisonment writing a cookery book. When, in 1949, Mao’s Red Army separated her again from not just her home but her embroidery factory and five little rental houses—worth £20,000 then (the equivalent of half a million pounds today)—she returned to Britain and vowed not to let go of life until either Japan or China had given her something back.

She started with the Foreign Office, which appeared to be helping everyone else with war reparations. She typed out long lists of the personal possessions she had lost, including her Steinway, her gramophone, and three hundred crystal glasses. She copied the Japanese army rice-paper receipt she had been given for her 1938 Ford Sudan, confiscated a few days after Pearl Harbor, and its accompanying letter from Colonel Shingo, promising to return it after the war. She itemized the crates of embroidered bed linen, tablecloths, napkins, and handkerchiefs that had vanished from their Chinese warehouses. She detailed the hat stands, newspaper racks, bridge tables, jelly molds, and even trays for visitors’ cards with which she had meticulously furnished the five houses she had built and rented out to the families of visiting U.S. servicemen. Then she attached a one-by-two-inch black-and-white photograph of each house and sent them to the Foreign Office with a series of letters asking whether she was entitled to compensation from Japan or from China.

The Foreign Office’s replies to this onslaught would have made Sir Humphrey proud. It was still too early (in 1953) to think about making a claim against Japan. “The peace treaty with Japan has not yet been ratified.” However, the Foreign Office could give Lilla advice about her real estate in China. It was extremely simple. All she needed to do was to register it with the Chinese authorities either in person or through a representative—oh, and this registration had to happen in China itself.

As both the Foreign Office and Lilla knew, this sounded simple but was utterly impossible. Lilla had experienced not a little difficulty in escaping the Communist takeover of China in 1949. Her two nephews who had been with her had been interrogated for three months before being finally granted exit permits. A German national had been casually shot while being questioned. Lilla, fast approaching her seventieth birthday, could not return to China. Nor would any Chinese person have dared make contact with a Westerner. But Lilla, still leafing through photograph albums of Chefoo and her houses there, was not going to let civil war, revolution, or even unsigned peace treaties impede her.

The next stop was the Chinese embassy in London. Lilla sent them another copy of her lists, receipts, and photographs. Not without reason did the term “mandarin” originate in China. The embassy’s commissioners fired off a response that would have thrown most people. It would be more appropriate, they replied, if Lilla were to write them in Chinese. But, like all good great-grannies, Lilla was far from ordinary. She had been born and brought up in China, chiefly in the hands of Chinese-speaking amahs. A Chinese version of her missive was shortly winging its way back.

Without the slightest hint of embarrassment, the commissars replied in the Queen’s English. A thousand years of bureaucratic experience made it clear where they believed responsibility lay. After the outbreak of the Second World War, Mrs. Casey’s [Lilla’s] property was confiscated by the Japanese authorities occupying the city, and some of it was destroyed by them. After the end of the war, the property was occupied by Chiang Kai-shek’s soldiers, who completely destroyed it. Therefore the Casey property had long ceased to exist during the Liberation of Chefoo.

Now, Lilla knew that this was not quite true. One of her nephews had sneaked around Chefoo after the Communists had arrived and had seen that all her houses were standing, although anything removable, including the plumbing, had been ripped out. She wasn’t prepared to give up. As she rounded the corner into her eighties, she followed up every reported nuance of Far Eastern foreign policy, sending letters off to the Chinese embassy, Japanese embassy, and the Foreign Office. When she hit ninety, Lilla’s distinctly healthier identical twin, who hadn’t spent several years being half starved in a concentration camp, died of old age. Then Lilla’s own children, both in their seventies, also went. But Lilla, keeping to her vow to win something back before she died, stormed on, pen in hand.

Eventually, in the early 1980s, the tide turned. After thirty years of isolationism, China needed to borrow money from the West. Before it could do this, it had to show that it could honor its debts. It turned to face its most determined foe, the ninety-nine-year-old Lilla.

Her writing a little shaky by now, Lilla asked her grandson to fill in all the forms. He attached yet more copies of all her lists, receipts, and photographs and sent them off from his ministerial office (he was secretary of state for energy). Lilla began to plan her funeral.

Then the British government department dealing with these claims against China wrote back to Lilla’s grandson. It said that of course it would be happy to process Lilla’s claim, but there was one small administrative problem. This was that Lilla’s British passport, issued in 1939, no longer made her British. Along with tens of thousands of other British people whose families had furthered the British Empire’s interests abroad, Lilla was discovering now that there was no more empire. Britain didn’t really want its colonies back.

In order to claim under the arrangements with China, Lilla had to provide her birth and both of her marriage certificates to prove her nationality and changes of name. Though she had survived the Boxer Rebellion, two world wars, two concentration camps, and the Red Army’s “Liberation” of China, these documents—funnily enough—weren’t on hand.

Lilla’s grandson, who had inherited some of her letter-writing skills, wrote back to point out that these were documents that couldn’t possibly be available. Six months later, in May 1982, Lilla heard that her claim had been approved. “Now I can go to Heaven,” she wrote, and went. Luckily her departure was prompter than the arrival of the check. For when it came, instead of returning the half-million pounds she was expecting, it was for £1,400. She had been paid just one-fifth of the 1935 value of her houses alone. If Lilla had been around to discover that, she would have been so angry that I think she would still be alive today.

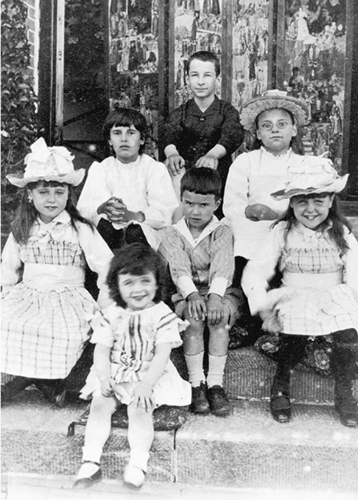

Ada and Lilla, or Lilla and Ada? Chefoo, 1890.

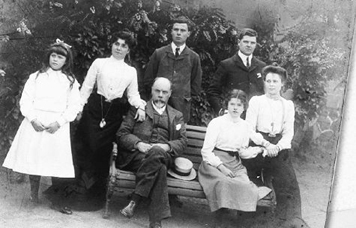

The family Lilla left behind. The Eckfords in Chefoo, shortly before Ada’s wedding to Toby Elderton in December 1901. From left: Dorothy, Alice, Andrew (sitting), Vivvy, Reggie, Edith, and Ada (both sitting).

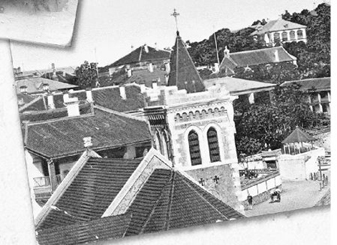

The spire of St. Andrew’s Church with Consulate Hill rising behind, Chefoo.

Lilla and Ada on the left. On the right, Toby Elderton, the artist who painted this, and Ernie Howell—all weeping because they are unable to obtain leave for Chefoo’s September race meeting, 1901.

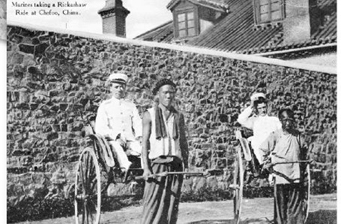

The navy on leave.