Lilla's Feast (6 page)

Authors: Frances Osborne

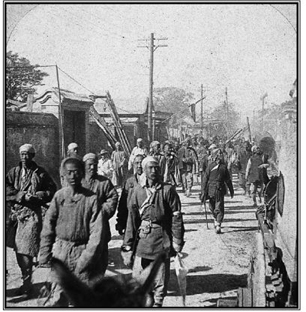

Boxers on the streets of Tientsin, 1900

The most curious Boxer target, however, was the railway system. Railways were not just “an obvious manifestation of foreign intrusion,” writes Frances Wood in her superb account of treaty-port life,

No Dogs and Not Many Chinese,

but—in as clear a sign as any that nations need to stop and think before imposing their own cultural values upon others— the railways also directly interfered with Chinese traditions. The rail tracks altered the feng shui of the land, thus bringing bad luck to all the areas in which they were laid. Passing trains potentially shook the tombs of ancestors, preventing their spirits from resting in peace. It was even alleged that the foreigners buried a dead Chinese under each railway sleeper—perhaps a metaphor for the jobs lost on the roads and canals. And in the second week of June 1900, the Boxers dug up as much of the Peking-Tientsin Railway as they could.

One week later, Western troops stationed at Tientsin seized several forts that controlled access to the city, forcing the imperial court to back either the Boxers or the treaty porters. Fearing a popular rebellion if it sided with the West, the court took up the Boxer cause—in a dramatically unsuccessful attempt at self-preservation—and a full-scale war broke out. The Boxers took the endorsement as encouragement to do their worst, and they swept inland, murdering any Chinese Christians, missionaries, and their families that they could find. In one town, the Chinese governor made the grand, and apparently brave, gesture of offering all the local missionaries protection. And then, when they arrived, he slaughtered every man, woman, and child.

For the foreigners, the most celebrated area of action was in Peking itself. There, everyone retreated into the American, British, Russian, German, and Japanese legations—diplomatic compounds—that nestled side by side in the city, barricading themselves in with sandbags, timber, and whatever furniture they could find. Between June 20 and August 14, an infamous fifty-five days, they were under siege, resorting to eating their ponies and horses, which had been performing in the May races shortly beforehand.

However, as the Boxers had cut the Peking-to-Tientsin telegraph along with the railway, the news flow at the time was limited. And some confusion over events arose. On July 5, the

New York Times

splashed the headline ALL FOREIGNERS IN PEKING DEAD, then, eleven days later, printed the lurid details of the alleged massacre: FOREIGNERS ALL SLAIN AFTER A LAST HEROIC STAND—SHOT THEIR WOMEN FIRST. But when the rescue force—an early United Nations–like combination of twenty thousand Japanese, Russian, American, British, and French troops—arrived in August (to be followed later by a German contingent), they found just seventy of the several hundred foreigners dead and the rest alive.

Foreign retribution was severe. “Russian and German troops in particular embarked on a campaign of rape and terror. Hearing that valuables were sometimes hidden in coffins along with dead family members awaiting an auspicious date for burial, they broke open any coffins they could find and even dug through the cemetery, flinging bodies away to be eaten by stray dogs.” The rest of the foreign soldiers set about sacking the palatial red-walled maze of the Forbidden City and beheading every Boxer they could find, grimly posing with their victims for photographs like big-game hunters who had tracked down their prey.

And the effect on the Chinese imperial court of first siding with the Boxers and then losing to the foreigners yet again would turn out to be disastrous. Various financial and political penalties were imposed upon it by the occupying powers. But the most demeaning outcome was perhaps the breaking of the majestic isolation in which the imperial court had kept itself, as the empress dowager now found herself holding receptions—tea parties, I imagine—for the wives of foreign diplomats. And, in the longer term, with the Boxers and their antiforeignism defeated, the young Chinese started to examine their country’s own fallible imperial institutions in their search for a solution to China’s problems, so marking the first step on the road to a tumultuous and bloody upheaval.

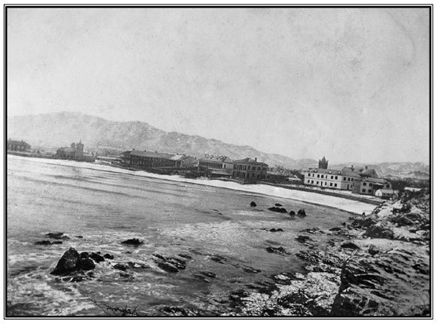

Chefoo, despite being an obvious Boxer target with both the Chefoo school for the children of missionaries and the bases of several missions in the town, seems to have been spared the worst. The clearest account is in a history of the school, which suggests that the town was threatened only for a week, and although the children “slept with a pillow-case containing a complete change of clothes ready by their beds,” they never needed it. Nonetheless, it must have been terrifying for those there. One former China resident writes that her missionary parents first ran to Chefoo from their station inland and from there fled China altogether, “travelling steerage” to Japan, her mother sitting up all night “to keep the rats off her babies”—including the author, who was just a few months old at the time.

First Beach from Consulate Hill, Chefoo, 1900

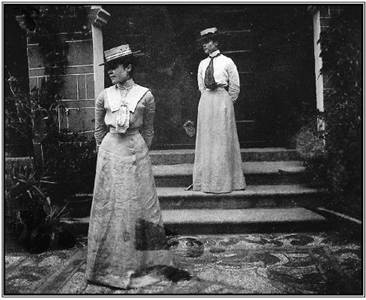

The Heavenly Twins: Ada and Lilla, Chefoo, 1901

Although the foreign forces took Peking in August 1900, the military campaign throughout the rest of the country dragged on, leaving several thousand troops stationed in the treaty ports. The treaty-port residents took it upon themselves to entertain them. There were tea parties in the afternoon, regimental balls in the evening, and hunting at dawn the next morning in the countryside around the treaty ports. And when the cities turned into saunas the following summer, the soldiers decamped to seaside resorts like Chefoo whenever they were given leave. There, the entertainment went on. There were thinly sliced and peppered cucumber sandwich picnics at the temples in the hills; early-morning canters kicking the sand up along the beaches; energetic boat trips with well-muscled arms used to wielding swords turned to pulling oars through the water as far as the islands that circled the bay; race meetings at the track on the far side of the old town, with bets and adrenaline running high; and dancing whenever there was the slightest reason to do so. And with all too few young women around, Lilla’s and Ada’s days were bursting at the seams with invitations.

It was a high time for the twins. They were nineteen years old and just back from finishing school in Europe. Those impish grins had blossomed into flirtatious flickers. The heart-shaped faces had softened. Their thick, dark hair was piled up on their heads, as the fashion dictated. But those two pairs of blue eyes still sparkled as if their owners were just twelve years old.

Lilla and Ada were pretty and knew it. They knew how to hold themselves in a corset; move their arms gracefully in the lightly frilled, high-collared shirts of the moment; step, not stride, in slimmed-down skirts; and perch their boaters at just the right angle. And they knew how to flirt. “They were extraordinarily interested in pleasing men,” I’m told.

Their mother, Alice, showed them her other ways of making a man happy, too. How to make a room look inviting, pulling back the furniture to open it up yet not placing the chairs so far apart that a secretive whisper couldn’t travel from one to another. How to bring a garden indoors without creating a greenhouse. How to display the latest tastes in fashion, art, and music so that your husband feels he is ahead of his peers. How to keep a house fresh, the air so gently scented that you long to breathe in yet more of it, without it growing too hot or too cold inside. How to turn your kitchen into an ever-simmering workshop of succulent roasts and irresistible sweet bakes and soft spices to tease the tongue—because, however many servants you might have cooking for you, they would only be as good as you yourself could teach them to be. These talents, Alice taught her daughters, were the tools for marriage, the tools for the only life that lay ahead of them. These were the unseen keys, I can almost hear her murmuring, to unlocking a husband’s heart. Spoil him rotten, she would have whispered, cater to his every need, and he will not be able to help himself but show you love in return. And as Lilla and Ada watched Andrew dote on their mother, his eyes following her every time she swept in or out of the room with a rustle of silk petticoats, they could only have agreed.

Lilla also had charm. Her stammer gave her the air of an innocent about to surrender. And to keep up with Ada, she tried to please. Ada simply swanned around. Then that was Ada, everyone says—she never had to try. Unlike Lilla, whose need to work at whatever she turned her mind to meant that, even in her nineties, she would still have a young man eating out of the palm of her hand within minutes. At nineteen, however, the pair of them were dynamite, an ever-shifting double image tantalizing admirers who found it hard to tell which one they were addressing. They had endless, breathless energy with which to picnic, ride, play tennis, chatter, and dance until dawn. Their feet barely touched the ground. And the soldiers who came to Chefoo, Lilla said, called them “the H-H-Heavenly Twins”—a nickname stolen from a contemporary popular novel about a pair of wicked but irresistibly engaging children. One of Ada’s grandsons sent me a cartoon from New Zealand. It was drawn in China, that summer of 1901. It shows several officers weeping because they weren’t given leave to go to the races in Chefoo and see the leaping pair of parasoled figures in pink and blue, marked THE HEAVENLY TWINS.

Then, just as Lilla thought they were having such a good time that she never wanted it to stop, Ada fell in love. And it wasn’t just a passing infatuation. Ada was head over heels in the going-to-get-married, unstoppable sort of love with a naval officer called Toby Elderton. Toby was tall, handsome, and a bit of a hero in Chefoo. He had been in charge of the ships that had ferried the rescue troops at breakneck speed to Peking, and he had already won one of the top British military medals, the Distinguished Service Order, twice over. He dazzled Ada with his self-assurance and charm. He was already thirty-six years old. So sweeping a nineteen-year-old girl off her feet must have been a walk in the park.

Part of Lilla would have been thrilled for Ada. Marriage was what they had been brought up to do. A husband was their career. And Ada was doing just that—and basking in the romantic glow that had seeped out from the pages of the novels they had read.

But Ada was mesmerized and could barely take her eyes off Toby. She dressed for him, wanted to spend time with him alone. She stopped speaking to Lilla quite so much in their private language—and started speaking to Toby about things she wouldn’t repeat to her sister.

The rest of Lilla must have been quite desperately jealous.

Jealous not just of Ada, who for the first time since their birth had something Lilla didn’t have and couldn’t simply demand to have as well—but, as having an identical twin is like already having a husband, a wife, a lover, she must have been deeply jealous of Toby, too—his arrival making her ache in a place that she couldn’t quite pinpoint. Ada’s glazed, flushed-cheeked look haunting her and her nights plagued by disturbing images of Ada disappearing up an endless church aisle, her rippling train slithering through Lilla’s outstretched fingers each time she tried to grasp it.

The visceral umbilical cord that had, until then, still joined the two of them, was beginning to tear.