Lion of Jordan (57 page)

Authors: Avi Shlaim

Some observers thought that Hussein lost his nerve during the crisis. A more likely explanation was that, realizing a showdown was inescapable, he was simply biding his time and giving the fedayeen enough rope to hang themselves. He refrained from drastic action because he did not wish to compromise his position as king of the whole Jordanian nation. Three stages can be discerned in his policy towards the PLO in 1970: conciliation, containment and confrontation. Hussein was extremely patient by nature and knew the importance of timing. He wanted to leave his people in no doubt that he had done everything in his power to avoid the shedding of blood. The hijacking of planes and the holding of hostages finally tipped public opinion at home and abroad against the fedayeen. The time for action had come. On the evening of 15 September,

Hussein summoned his closest advisers to an emergency meeting at his house in Al-Hummar on the outskirts of Amman. Among those present were Wasfi Tall, Zaid Rifa'i, Sharif Zaid bin Shaker and Habis Majali. All of these men had been urging him to crack down on the fedayeen for some time. The military men estimated that it would take the army two to three days to clear the fedayeen out of the major cities.

Before ordering the army to move, Hussein decided to dismiss the civilian government and appoint a military government headed by Brigadier Muhammad Daoud. Daoud was in fact a Palestinian, but he was loyal to the king and favoured firm action in defence of the regime. Hussein preferred to see the coming conflict not as a war between Jordanians and Palestinians but as a contest between the forces of law and order and the forces of anarchy. Most of the members of this government were military men though not all of them were high ranking. Adnan Abu-Odeh, an obscure major in the General Intelligence Department (Mukhabarat), was appointed minister of information. Earlier that year he had been sent to the UK to attend a psychological warfare course. Abu-Odeh came from humble Palestinian origins and had been a schoolteacher and member of the Jordanian Communist Party before joining the Mukhabarat. Hussein knew all this, but he greatly respected the sharpness of his analysis and his eloquence. Abu-Odeh's task was to explain the government's policy and to conduct psychological warfare in the middle of the military operation. His selection for the post reflected Hussein's desire to have Palestinians among his ministers and his keen awareness of the importance of public relations. He was later to become one of Hussein's closest political advisers. One day Abu-Odeh asked the king what was the most difficult decision he ever made. The king replied, âThe decision to recapture my capital.'

32

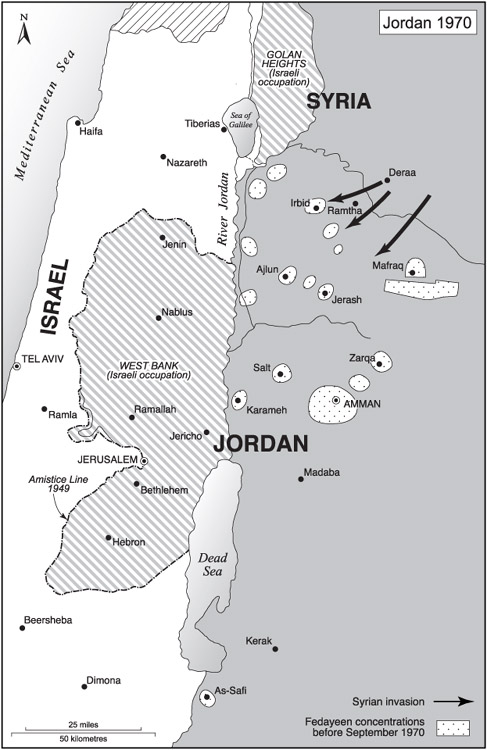

Early in the morning of 17 September the civil war began. The 60th Armoured Brigade entered Amman from different directions and started bombarding the Wahadat and Husseini refugee camps, where the fedayeen had their headquarters. The fedayeen were well prepared and offered very stiff resistance. The army pounded with tanks, artillery and mortars not only the fedayeen strongholds but also the Palestinian population centres in and around Amman. Heavy fighting continued without a break for the next ten days. At the same time the army surrounded and bombarded other cities controlled by the fedayeen â Irbid, Jerash, Salt and Zarqa â but refrained from entering them. Here

there was no house-to-house and street-to-street fighting, as in the capital, but many buildings and blocks of apartments were reduced to rubble, and there were heavy casualties. According to PLO figures, the death toll in the first ten days of fighting was as high as 3,400. The initial estimate that it would take two to three days to dislodge the fedayeen from the cities turned out to be wide of the mark. As the days went by, Arab leaders stepped up the pressure on Hussein to put an end to the fighting and to reach a compromise with the fedayeen.

Jordanian fears of external intervention in the conflict were soon realized. On the morning of 18 September a small Syrian armoured force crossed the border near Rathma and headed for Irbid, which was under the control of the fedayeen. The 40th Armoured Brigade engaged the invading force in fierce combat, knocked out some of its tanks and managed to block its advance. Later in the day there was a second incursion across the border but on a larger scale. This time two armoured brigades with nearly 300 tanks and a mechanized infantry brigade were dispatched towards Irbid. The Syrian tanks had PLA markings, but the PLA had no tanks and it was obvious that the invaders were regular army units. The motives behind the Syrian invasion remained obscure, and no statement was issued to clarify them. It is the received wisdom that the Syrian leadership's aim was to help the guerrillas overthrow Hussein. But, if this was indeed the aim, it is not clear why the Syrian intervention was so cautious and circumscribed. A more likely explanation is that the Syrian leaders wanted to protect the Palestinians from a massacre by helping them to create a safe haven in northern Jordan from which they could negotiate terms with the king.

33

That evening Hussein convened an emergency meeting of his three-day-old cabinet. The purpose of the meeting was to get the cabinet's permission to call for outside help if it became absolutely necessary. Most of the ministers were soldiers and the king was their commander-in-chief, so they were rather surprised that the king chose to consult them rather than to issue orders. What the king said to the cabinet went as follows: âThe Syrians have entered the country and are approaching Irbid. Our troops are fighting back but the Syrians are still progressing. As a precaution we might need the help of friends, and I want you to give me the mandate to ask for such help if I have to do so.' Some ministers did not like what they heard, but only vague comments were made in response. Their faces revealed their displeasure. Noticing their

unease Hussein said, âGentlemen, I leave you alone to discuss the idea among yourselves. When you reach a decision, please call me.' And he left the room.

In the subsequent discussion two rather different attitudes emerged. One group of ministers saw this as an internal Arab affair and was adamantly opposed to asking for outside help. A second group thought that Jordan was engaged in an existential struggle for survival and saw nothing wrong with asking a friend to help, provided it was the US or Britain and not Israel. No one suspected that the friend could be Israel; they all thought that, because of the precedent of 1958, it would be either or both of the Western allies. At the end of the discussion, the second group prevailed, and the king was given the mandate he had asked for.

34

Sunday, 20 September, was a long and stressful day. Events on the battlefield influenced the manner in which Hussein used the mandate he had received from his ministers. His management of the crisis was also affected by the recurrent breakdown of communications between the palace and the US Embassy. Walkie-talkies were used some of the time, and the fedayeen who controlled the area round the embassy could eavesdrop on the conversations. Another constraint was the absence of direct âacross the river' contact with the Israelis. Zaid Rifa'i, the trusted aide, was by his monarch's side throughout the crisis and conveyed most of the sensitive messages to his Western allies. Hussein made his first request for help through the British Embassy because his normal channels of communications with the US Embassy were interrupted. He called for âIsraeli or other air intervention or threat thereof' against the Syrian troops and he asked the British government to consider this request and to convey it to Israel.

In Britain there was virtually unanimous opposition to military intervention. The experts in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office believed that the Palestinians would eventually win the struggle against the king and that it would be damaging to British interests in the Arab world to take action to save his throne. Peter Tripp, who served on the Jordanian desk in the FCO, explained the British predicament: âYou cannot just nail your colours to the mast and say well, we'll go down with the ship. I mean, there's a certain amount of self-interest in all this.'

35

The Conservative government headed by Edward Heath shared the view of the experts. Sir Alec Douglas-Home, the foreign secretary, advised the

prime minister that Western intervention would be deeply resented by the Arab countries: âThe Palestinian revolt strikes a very deep chord in Arab hearts. Any Western country therefore which intervenes to try to save Jordan will be involving itself in a deep quarrel in Arabia as a whole, the consequences and end of which none could foretell.' The other argument against intervention was stated even more bluntly: âJordan as it is is not a viable country.'

36

After discussion the cabinet rejected any idea of military intervention and feebly decided to transmit the king's message only to the Americans and to leave it to their discretion whether to convey the message to Israel.

37

The truth was that Britain had an each-way bet on the king and on Arafat.

Shortly after his conversation with the British ambassador, Hussein managed to contact the new American ambassador, Dean Brown, who arrived at the height of the hijack crisis and was taken to the palace to present his credentials in an armoured personnel carrier. Hussein made an urgent appeal for air strikes and air cover âfrom any quarter'. Hussein did not explicitly mention Israel this time but the substance of his appeal was passed on to the Israeli representative in Washington.

38

Kissinger and Nixon saw the Syrian invasion as a Soviet challenge that had to be met. Kissinger told Nixon that the Soviets were pushing the Syrians and the Syrians were pushing the Palestinians. Nixon shared the conviction that the Kremlin orchestrated the Jordanian crisis in order to challenge US credibility throughout the Third World. In his memoirs Nixon wrote, âWe could not allow Hussein to be overthrown by a Soviet-inspired insurrection. If it succeeded, the entire Middle East might erupt in war⦠It was like a ghastly game of dominoes, with a nuclear war waiting at the end.'

39

Kissinger and Nixon tended to see every regional conflict through the lens of their global rivalry with the Soviet Union; in their view, a Russian soldier lurked behind every olive tree in the Middle East. And both men vastly exaggerated the superpower dimension of the Jordanian crisis. There was no concrete evidence at that time to support the theory that the Soviet Union had instigated the Syrian invasion; the little evidence that came to light later on, in fact, pointed the other way. The Egyptian foreign minister, for example, noted in his memoirs that the Soviets made efforts to defuse the crisis and that they also asked Nasser to put pressure on the Syrians to end their military involvement in Jordan.

40

The perception of high stakes drove Kissinger and Nixon to respond

robustly to Hussein's plea for help. Nixon enthusiastically approved all the military deployments recommended by his hawkish adviser. Apparently, they appealed to his macho streak. âThe main thing', Nixon said, âis there's nothing better than a little confrontation now and then, a little excitement.'

41

Nixon ordered the 82nd Airborne Division on full alert; the Sixth Fleet to move demonstratively towards the area of tension in the eastern Mediterranean; a reconnaissance plane to fly from an aircraft carrier to Tel Aviv to pick up targeting information and signal that American military action might be approaching; and a warning to be delivered to the Soviets to restrain their Syrian clients. Kissinger preferred Israeli military intervention against Syria with America holding the ring against Soviet interference with Israeli operations; Nixon was reluctant to rely on Israel and wanted only American forces to be used if a confrontation could not be avoided. In the evening, however, Nixon received a more desperate message from Hussein, which led him to reverse his position on the use of Israeli forces. The message from Hussein said that the situation had deteriorated seriously; that Syrian forces occupied Irbid; and that the troops in the capital were disquieted. Hussein also said that air strikes against the invading forces were imperative to save his country and that he might soon have to request ground troops as well. Reversing his earlier procedure, Hussein asked the Americans to inform Britain of his plight.

Kissinger called Itzhak Rabin, the Israeli ambassador to Washington, and told him that the president and the secretary of state would look favourably on an Israeli air attack, that they would make up any material losses, and that they would do their utmost to prevent Soviet interference. Rabin said he would consult with Prime Minister Golda Meir, who happened to be in New York. Late that night Rabin called back with her answer. Israel would fly reconnaissance at first light. The situation around Irbid was described as âquite unpleasant'. Israel's military leaders assessed that air action alone might not be sufficient. But they promised to consult again before taking any action.

42

Monday, 21 September, was another momentous day. In Jerusalem, the cabinet, chaired by Yigal Allon, met in the morning to consider Hussein's extraordinary request. One group favoured the preservation and the strengthening of Hussein's regime. It argued that among all the Arab countries the Hashemite dynasty had the best relations with Israel. According to this group, the June War was a tactical mistake on the part

of the king that should not be allowed to damage the basically positive relationship between the two sides. This group also considered Hussein to be the most promising Arab candidate for a peace settlement. Another group was in favour of turning the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan into a Palestinian state. The more extreme members of this group advocated active Israeli support for the PLO in bringing this about. Yasser Arafat's declaration of independence in Irbid helped members of this group to press their case. They recommended allowing the PLO to achieve its goals and to gain control of the whole country. For them this was the ideal solution to the problem of Palestinian independence.

43